The next time you find yourself driving down historic Franklin Boulevard between Franklin Circle and West 50th Street, take time to notice what is different about the stretch of the Boulevard between West 32nd and West 38th Streets. It is entirely devoid of any grand houses--nineteenth century or otherwise. Relevant to this story, on the south side of that stretch just west of the Fairview Gardens Apartments, you'll see a large community garden that extends all the way to West 38th Street. You might imagine that at one time grand mansions graced this section of Franklin Boulevard, too. If you did, however, you'd be wrong, because this is instead where the now legendary Kentucky Street Reservoir once stood.

The Kentucky Street Reservoir was part of the City of Cleveland's first water works system. In March 1850, Cleveland Mayor William Case, in his inaugural address, noted Cleveland's extraordinary population growth in the preceding decade--from 6,000 in 1840 to 17,000 in 1850, an increase of 180.6%--and challenged City Council to address, among other things, the issue of providing a sufficient supply of "pure water" for this growing population. At the time, all of Cleveland's drinking water came from springs and wells. Water for other purposes, such as cleaning, was hauled in barrels up Superior Hill from the Cuyahoga River. Council took up the challenge and appointed a committee to study the matter. Over the course of the next two years, the committee examined the City's water needs, talked with experts both in the United States and Europe, and observed the operations of the water works systems in a number of large cities, including Cincinnati, then the nation's sixth largest with a population of more than 115,000 residents.

In a report delivered to the Mayor and Council in November 1852, the committee detailed its recommendations for the construction of a water works system that would provide, at least for the next decade, water for all of the city's needs, including sufficient pure drinking water for its burgeoning population, water for cleaning, water for "sprinkling" streets, and water for fighting fires. The committee also recommended that the Council hire Theodore Scowden, the engineer who had designed Cincinnati's water works system, to design Cleveland's new system. It appears Council quickly followed that recommendation, because, within a week, Scowden was, according to local news accounts, already at work as the Engineer for the City's Water Works Board. One year later in October 1853, after the State Legislature had in March authorized the project and the Cleveland electorate had in April approved its financing, Scowden submitted a report to City Council with his recommendations for the various component parts of the new Cleveland water works system including a reservoir.

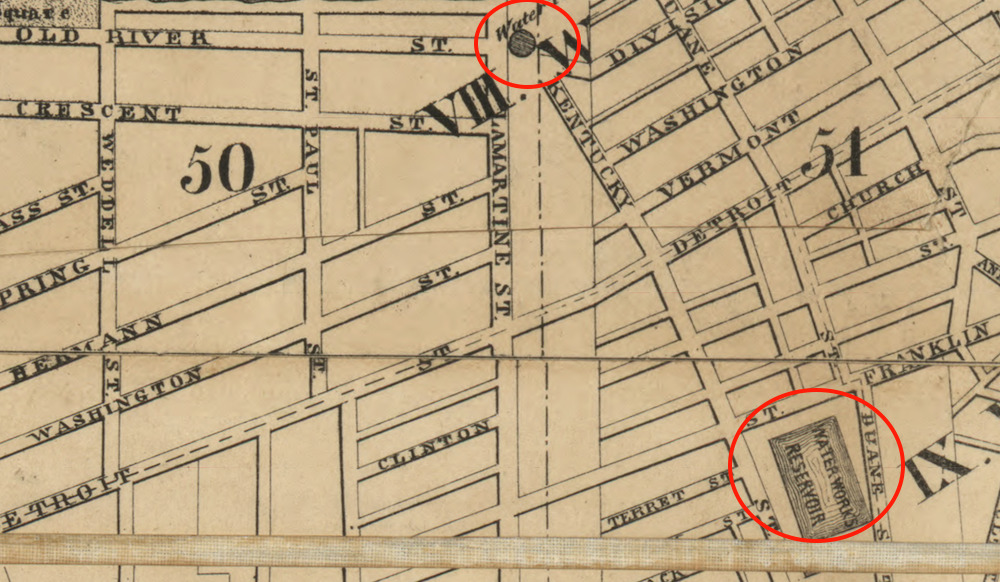

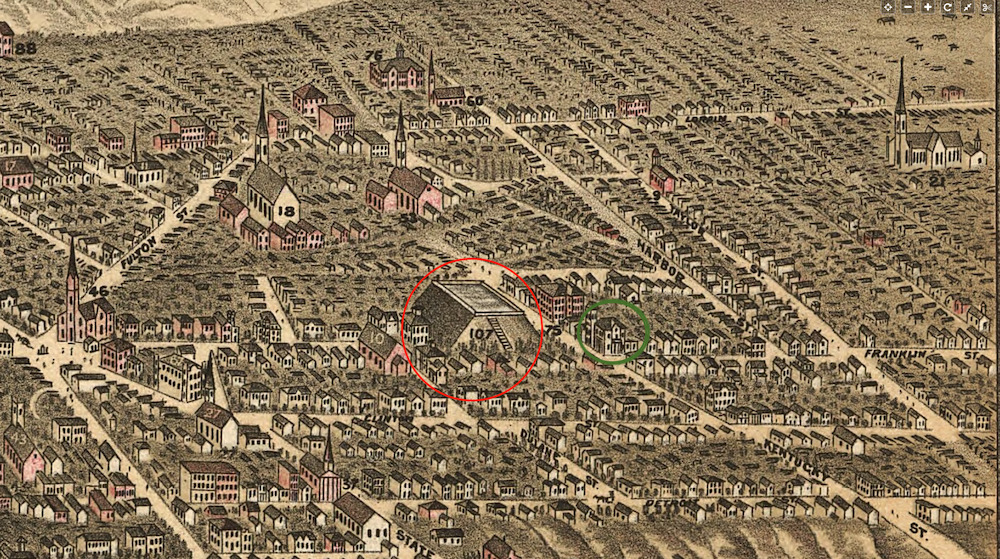

While Council's committee in 1852 had recommended that the reservoir for the new water works system be a masonry tower with an iron tank capable of holding one millions gallons of water, and that it be constructed on land near the intersection of Frontier (East 21st) Street and Euclid Avenue, Scowden instead recommended an earthen reservoir with a capacity of six million gallons, and that it be built not in Cleveland but across the Cuyahoga River in Ohio City. The site he recommended was a six-acre parcel of land located (north and south) between Franklin (Boulevard) and Woodbine (Avenue) Streets , and (east and west) between Duane (West 32nd) and Kentucky (West 38th) Streets. Scowden's reservoir recommendation appears to have been based on advice the City had received from local engineer George W. Smith, who was familiar with Cleveland's unique topography. According to newspaper accounts, Smith informed City officials that the higher elevation of the Ohio City site--it was 31 feet higher above the surface of Lake Erie than sites considered on the east side of the River--made it not only a safer engineering choice, but also a more cost effective one. While some had reservations over building the reservoir for the new water works system in another city, Council--perhaps anticipating that Ohio City would soon be annexed by Cleveland--approved Scowden's recommendations in a 6-2 vote on October 12, 1853.

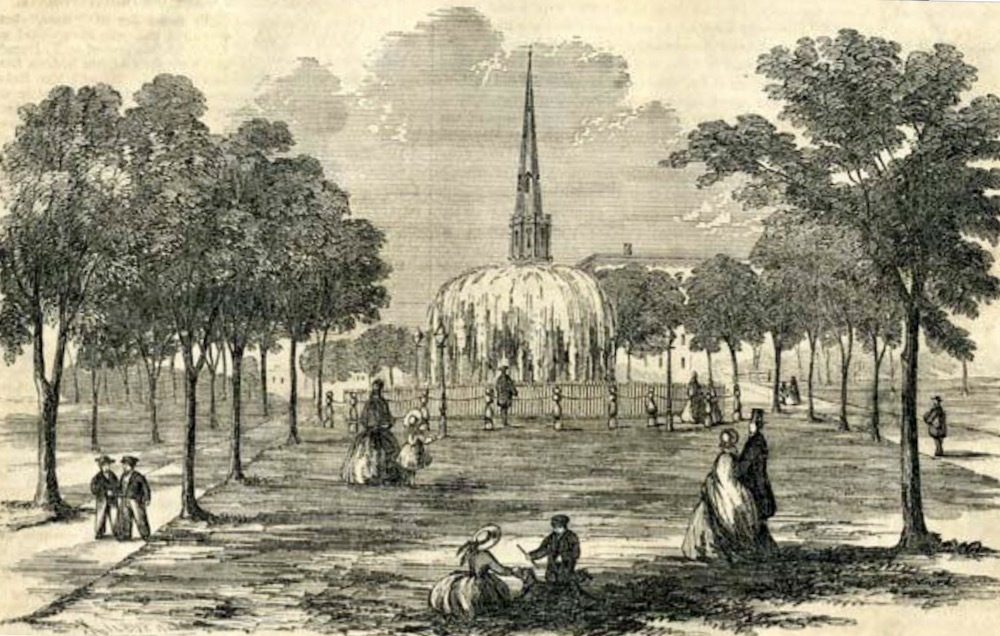

The Cleveland water works system designed by Theodore Scowden was constructed during the period 1854-1856. Its main components were an aqueduct located out in Lake Erie, 300 feet from shore and 400 feet west of the western terminus of the Old River Bed; an engine house on Old River Street (Division Avenue) near Kentucky Street, which featured two massive engines for pumping; the Kentucky Street Reservoir; and some 70,150 feet (13 plus miles) of pipeline on the east and west sides of the City, which, effective June 5, 1854, included the territory of the now annexed Ohio City. The total cost of the project was $500,000. During the construction of the water works system and in anticipation of the Ohio State Fair to be held in Cleveland in September 1856, the City also constructed a large stone fountain, 40 feet in diameter, at the center of Public Square. The fountain was fed water through a series of pipes that led from the Reservoir, down the hill to the Flats, then under the Cuyahoga River, and up Superior Avenue to the Square. The water works system was completed just before the Fair opened and the Public Square fountain, with its pure drinking water and its bursts of water some 30 to 50 feet into the air, became a big hit with visitors to the Fair.

The Kentucky Street Reservoir quickly became one of the most recognizable landmarks on the west side of Cleveland. It covered approximately four acres of the six-acre site upon which it was constructed and was built on a sloped 21-foot high, trapezoid-shaped embankment of sand and earth that at its base was 332 feet wide and 466 feet long. Atop this embankment was a 25-foot-high retention basin which was 100 feet wide at its base and 15 feet wide at the top. The exterior of both the retention basin and the embankment was covered with sod. At the top of the Reservoir--46 feet above the grade of nearby Franklin Street--was an eight-foot-wide gravel walk that encircled the basin and that was reached by ascending a flight of 70 steps on the Reservoir's north face. On the inside of the gravel walk-- known as the Promenade Walk--there was a wooden fence which enclosed the basin. A fountain in the basin jetted water into the air. The Reservoir's Promenade Walk, which at the time had the highest elevation of any man-made structure in the City, treated visitors to what people said was the best view of Cleveland and its surroundings. The Reservoir grounds themselves were beautifully landscaped with walks, shade trees and shrubbery.

The Kentucky Reservoir served as an important part of the Cleveland water works system for thirty years. It was abandoned as a reservoir in 1886 after completion of the new much larger Fairmount (80 million gallon) and the High Service (Kinsman - 20 million gallon) reservoirs on the City's east side. For a decade, the fate of the Kentucky Street Reservoir, unused and, according to neighbors, an eyesore and nuisance in the Franklin Avenue neighborhood, was uncertain. Some officials wanted to dismantle it and sell the property to a residential developer, but City lawyers warned that this could cause the land to revert to the heirs of its previous owner, Benjamin F. Tyler, from whom it had been appropriated for public purposes in 1854. Others wanted to preserve it as a storage facility for the Water Works Department.

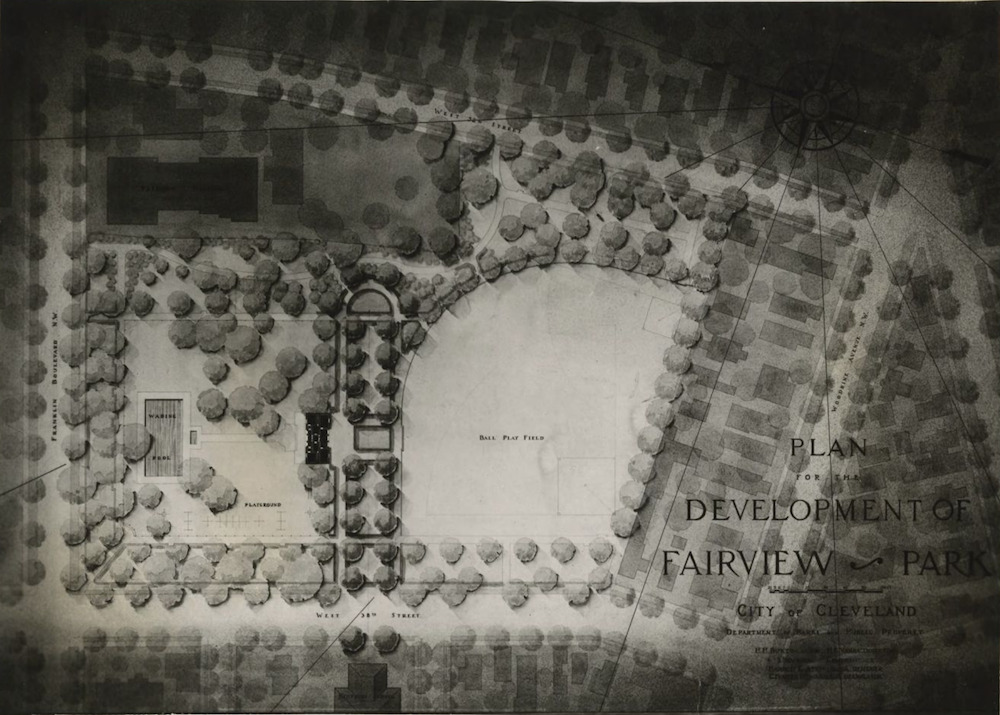

Finally, in 1897, the City decided to convert the old Reservoir into a city park after receiving a petition from the Western Improvement Association (WIA), an organization of west and south side residents formed in 1894 to advocate for public improvements to their neighborhoods. (WIA member Horace Hannum who led the drive was the owner of the Sarah Bousfield House which was located diagonally across Franklin from the Reservoir property.) Over the course of the next year, the Reservoir was razed, and dirt, sand and other materials from it were used to create a terraced park in its place. The new city park, which opened in April 1898, was dubbed "Fairview," because from its terraced hills visitors could get a "fair view" of Lake Erie. While the name stuck, its "fair views" were lost to park visitors after 1912 when the City flattened the hills and trucked away much of the dirt, sand and other materials for use in the construction of Edgewater Boulevard. In 1917, when World War I was creating much anti-German sentiment in the city, German Hospital located next door to the park was renamed Fairview Park Hospital, the name it is still known by, even though in 1955 it moved to its present day location on Lorain Avenue in the Kamms Corner neighborhood of Cleveland.

In the 1930s, Fairview Park was extensively redeveloped during the administration of Mayor Harold Burton. A playground and wading pool for children--many undoubtedly students attending nearby Kentucky Elementary School--were added in 1938. Walking paths and a baseball diamond were also added to the park during this period. A section of the park was also set aside during this period as a vegetable garden which was tilled for decades by school children under a Cleveland public schools agricultural program. In the 1980s, this school garden became a community garden for residents of the Ohio City neighborhood. Today, the former site of the once famous Kentucky Street Reservoir is home to both the community garden known as Kentucky Gardens, located on the northern part of the old Reservoir property, while what is left of the original Fairview Park now occupies only the southern part of the historic site.

Images