On September 15, 1957, the congregation of Temple Beth-El gathered to dedicate the first built synagogue in Shaker Heights. Despite the city's substantial Jewish population, the physical development of civic associations in the suburb had only recently begun to be realized. Under the spiritual leadership of Rabbi David L. Genuth, Temple Beth-El would become a refuge for modern Orthodox Jewish religion, culture and education within Shaker Heights.

On July 29, 1951, more than 500 guests of Temple Beth-El convened at the Hotel Hollenden ballroom in downtown Cleveland to witness the dedication of the congregation’s Sefer Torah. Speakers at the ceremony included Rabbi David L. Genuth of Temple Beth-El, Ohio Governor Frank Lausche, and Mayor John W. Barkley of Shaker Heights. Rabbi Genuth, spiritual leader and founding member of the congregation, addressed the crowd with his vision for Temple Beth-El. “Our doors shall be open to all seeking a refuge and a haven from the troubles of the world, regardless of race, color or creed. Our temple shall be a sanctuary to the poor and the rich, the weak and the strong.” Governor Lausche followed, observing the long and enduring history of Jewish persecution. Mayor Barkley then welcomed Temple Beth-El to Shaker Heights, remarking “It is a people that make a city great. Your organization will make a valuable addition to our fair city.” While Rabbi Genuth founded Beth-El to cultivate traditions of Jewish Orthodoxy within Shaker Heights, it was fitting for the public ceremony to be held in the neighboring City of Cleveland. Efforts to institutionalize Jewish life in Shaker Heights had only recently begun to be realized. The physical development of Jewish civic associations in the suburb was noticeably overdue, as was the newfound municipal support for their creation.

Although not reflected in physical structures, Shaker Heights had long been home to an active Jewish community. As early as the 1920s, Cleveland’s many Jewish newspapers announced the births, deaths, bar mitzvahs, confirmations, business ventures, real estate purchases, and general comings-and-goings of the Shaker Heights community. Increasingly throughout the 1930s, Jewish clubs and organizations regularly met in Shaker Heights homes for a variety of events that included garden parties, tea socials, sewing circles, and discussion groups. While hosting events in homes was common during the era, official meetings and charity events of Jewish clubs such as Kinsman-Shaker B'nai B'rith, Shaker Heights Masada, and Hadassah branches were typically held outside the suburb’s boundaries.

As evidenced by these activities, a 1937 population study estimated that fifteen percent of the Shaker Heights population was Jewish. This accounted for over 3,600 individuals in 837 families. Fifty-seven percent of these Jewish families were members of congregations. Despite the presence of a substantial Jewish population, there were no dedicated houses of worship in Shaker Heights. This lack of grounded religious organizations was partly due to the community’s ties to synagogues in both Cleveland and, increasingly, Cleveland Heights. Although shrinking in size and influence, large Jewish communities centered in Glenville and along Kinsman in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood remained the hubs of religious and cultural life through the 1930s.

The dearth of Jewish institutions within Shaker Heights, however, can also be attributed to exclusionary real estate policies implemented by The Van Sweringen Company during the 1920s. Restrictive covenants in deeds issued following 1925 deterred property sales to Jews, African Americans and Catholics, and strict building standards discouraged types of religious architecture. While the deed restrictions did not explicitly deny home-ownership on the basis of religion or race, the covenants required the re-sale of a home be approved by the majority of neighboring property owners. Masked under the guise of community standards, the process discouraged both real estate agents and homeowners from entering into negotiations with non-white and Jewish prospective buyers. Despite a Supreme Court decision declaring restrictive covenants unenforceable in 1948, the practices were commonly employed and actively hindered access to housing in many Shaker Heights neighborhoods well into the 1950s.

Because many properties in the southeast region of Shaker Heights were developed outside the Van Sweringens’ control, restrictive covenants were less likely to impede Jewish home ownership in the Moreland and Lomond neighborhoods. A substantial Jewish community emerged near the intersection of Kinsman and Lee Roads during the 1940s, providing increased urgency for the development of religious institutions.

Three new Jewish congregations in Shaker Heights were chartered during this period of Jewish settlement. Established in 1947, the Temple of Shaker Heights was led by Rabbi Albert L. Raab of the N’Vai Zedek Congregation in Mount Pleasant. The congregation initiated fundraising for a $250,000 religious complex to be located in the Kinsman-Lee neighborhood, but the project was never realized. Temple Emanu El was founded that same year, holding both services and religious school at Moreland School. The Reform Jewish congregation moved their services to Plymouth Church of Shaker Heights within the year. Congregants continued to hold religious services and classes in Shaker Heights until 1954, when land was acquired to construct a synagogue in University Heights. The Suburban Temple, a splinter of Emanu El, was established in 1948. The congregation held services in the Lomond School Auditorium until securing land in Beachwood to construct a temple in 1954. At midcentury, the Emanu El and Suburban Temple congregations were in the process of raising funds to construct synagogues. While the city of Shaker Heights remained devoid of any permanent Jewish religious edifices, efforts were underway to ground religious life in the Kinsman-Lee neighborhood.

In the fall of 1950, four families gathered at the home of Rabbi David L. Genuth on Hildana Road for the purpose of establishing the “First Hebrew Sanctuary in Shaker Heights.” Aspiring to fill the “long apparent need” for Orthodox services in the suburb, the small group founded Beth-El. Aided by the Shaker Heights School Board, Orthodox services were quickly scheduled to be held at the Moreland School Auditorium on Saturday mornings. Within four weeks, the congregation was granted a charter by the State of Ohio.

Reputed for his philanthropic, civic and cultural endeavors, Rabbi Genuth quickly grew the Beth-El congregation. The Rabbi had long been an active and influential member of Cleveland’s Orthodox Jewish community. Between 1933 and 1950, he acted as spiritual leader of the Kinsman Jewish Center in Mount Pleasant. Modern Orthodox services were implemented under his guidance in 1937, and the congregation grew to over 400 families by 1940. The Rabbi had also been instrumental in the development of the Cleveland Zionist Society, and helped found both the Jewish Community Council and the Shaker-Kinsman B’nai B’rith. Like many congregants of the Kinsman Jewish Center, Rabbi Genuth relocated from Mount Pleasant to a home in Shaker Heights’ Kinsman-Lee district by the early 1940s. With the announcement of the new congregation in Shaker Heights, both loyalties to the Rabbi and a desire to worship within the emerging Kinsman-Lee community aided in its rapid growth.

In February, 1951, Beth-El celebrated its new charter at the Heights Jewish Center in Cleveland Heights. That August, the sacred Sefer Torah was presented to the congregation and blessed at the Hollenden Hotel celebration. Efforts were well underway to create a permanent space where Jewish religious life could be observed within the boundaries of Shaker Heights. A frame dwelling, rumored to be the oldest standing farmhouse in Shaker Heights, was acquired by the Beth-El congregation in July of 1951 at 15808 Kinsman Road. The grounds of the new property were consecrated, and the temple dedicated in August. Before a capacity crowd, a procession led the congregation’s Torah scrolls into the building. While the modest structure was only envisioned as a temporary home, Temple Beth-El was now equipped to provide for the educational, cultural and religious needs of the community.

Due to limited facilities at the farmhouse, High Holy Day Services were held in the Moreland School Auditorium in 1951. Beth-El histories recount these ceremonies as the first time in the history of Cleveland that “a modern Orthodox congregation held services where men and women sat side by side and worshipped together.” The years that followed witnessed a flurry of organizational and fundraising activities. A Sisterhood was organized, a Sunday School established, cemetery lands purchased in Mt. Zion Memorial Park, existing grounds renovated to meet city codes, and plans prepared for the construction of a new synagogue. Doors remained open to the surrounding community daily throughout these years, with Rabbi David Genuth offering counsel to all that entered the Temple in Shaker Heights.

On August 22, 1954, Rabbi Genuth stood before his congregation to perform groundbreaking rituals and initiate construction of Beth-El’s new synagogue. Below an open tent fronting the farmhouse, Mayor Barkley delivered the principal address to commemorate the establishment of the city’s first permanent Jewish temple. The Mayor was presented with a bound Hebrew and English copy of the Song of Solomon, which had been printed in the recently formed state of Israel. The turning of the soil symbolized the institutionalization of Jewish religious life in the community of Shaker Heights.

The successes of Temple Beth-El can in part be attributed to its close ties with the municipal government. While the City had already shown a willingness to work with the Jewish community in providing access to its schools for use in religious services during the late 1940s, a personal relationship between Rabbi Genuth and Mayor Barkley helped color the interaction between these two institutions. Upon news of John Barkley’s election in 1950, Rabbi Genuth had penned a letter of congratulations to the Mayor-elect. The written correspondence evolved into a friendship. From the outset, the congregation found city officials to be supportive of their ambition to build a Jewish sanctuary in Shaker Heights. Permissions were secured by both the Mayor of Shaker Heights and the Superintendent of Shaker Heights Schools to use the Moreland School Auditorium for forum meetings and religious services. Upon Barkley’s subsequent acceptance of invitations to participate in Beth-El’s public ceremonies, relationships were forged between the Mayor and numerous congregation members.

Through Mayor Barkley’s participation in public ceremonies, a precedent was set for the involvement of future administrations in Beth-El’s religious affairs. Personal ties would also be built by Rabbi Genuth with Mayors Wilson G. Stapleton and Paul K. Jones. The various Mayors participated in nearly all public events during these early years, including annual officer installations, construction-related ceremonies, ribbon-cuttings, and dedications. This eventually extended to their attendance at significant religious observations, and a tradition emerged that the Mayor of Shaker Heights visited services on High Holy Days. The friendship and goodwill between municipal leaders and the congregation proved beneficial through the many difficult years of inspections, planning and construction of Temple Beth-El’s new structure.

On September 15, 1957, Governor Frank Lausche and Mayor Wilson G. Stapleton of Shaker Heights convened to celebrate the dedication of Temple Beth-El’s House of Worship. The American colonial-type structure, situated at the rear of the historic farmhouse, was officially opened as the first built Synagogue in Shaker Heights. Designed to reflect the architectural motif of Shaker Square, the building merged traditions of the Jewish community and a historically exclusionary suburb. The dedication of a synagogue did not mark an end to the suburb’s troubled history of discriminatory real estate practices. The symbolic support offered by the City of Shaker Heights to Temple Beth-El throughout the 1950s, however, indicated the beginnings of an institutional shift towards inclusivity that would later become a cornerstone of the city’s identity. Fittingly, the banquet that followed the official opening of Beth-El was held in Naiman Hall of the new synagogue.

Under the leadership of David Genuth, Temple Beth-El continued to expand. The synagogue become a refuge for modern Orthodox Jewish religion, culture and education within Shaker Heights. The congregation grew to 450 members by its tenth anniversary, 80 percent of whom lived in the immediate vicinity of the neighborhood. Even as the Kinsman-Lee Jewish community dispersed to the outer-ring suburbs of Cleveland during the 1960s and 1970s, Temple Beth-El maintained many of its members and a full schedule of religious services. The historic synagogue regularly reached full capacity on High Holy Days. After nearly twenty-four years of service as the spiritual leader of Temple Beth-El, Rabbi Genuth passed away on February 23, 1974. The Shaker Heights congregation continued on its path of fostering the traditions of modern Orthodox Judaism for the next twenty-five years. Attrition, continued decline in the surrounding neighborhood’s Orthodox Jewish population, and the burdens of an aging structure impelled the sale of the synagogue to the City of Shaker Heights in 1998. Under the spiritual leadership of Rabbi Moshe Adler, the Beth-El congregation merged with 35 members of Beth Am to form Beth-El — The Heights Synagogue in January, 2000. The congregation is currently located in Cleveland Heights.

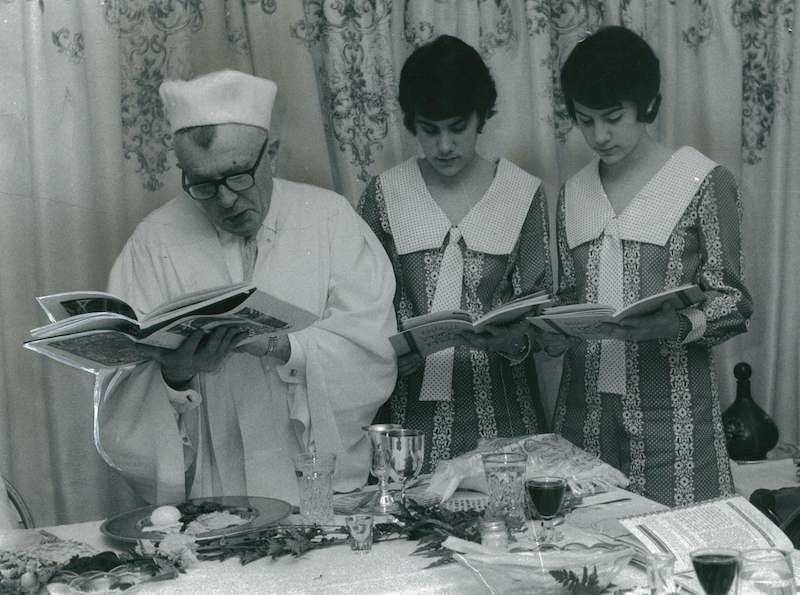

Images