Librarian William H. Brett established the open shelf system at Cleveland Public Library, the first metropolitan library in the United States to do so. Despite the main library then operating in cramped quarters, he found a way to create Cleveland Public Library's first children's room. And he fought back against local leaders who opposed the library's purchase of fiction novels for the reading public. Brett's biggest challenge, however, may well have been building the Carnegie West branch library.

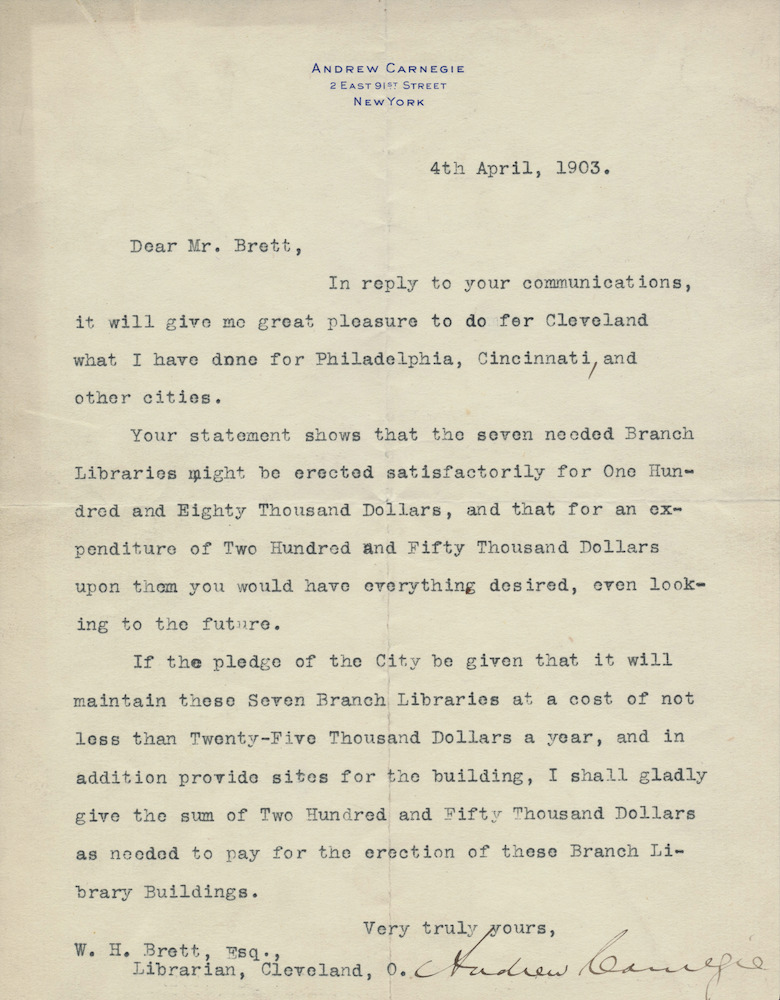

In 1903, "Steel King" Andrew Carnegie pledged $250,000--today's equivalent of eight million dollars--for seven new branch library buildings in the City of Cleveland. One of the existing branches that was intended to benefit from the pledge was the West Side branch library. Opened in 1892, it was Cleveland's first branch library. Since 1898, it had occupied a building on Franklin Boulevard near Pearl (West 25th) Street. The building--still standing and known today as the "Cinecraft Building"--had been designed and built for the branch, but was owned by People's Savings Bank which leased it to Cleveland Public Library.

Just two days after the newspapers reported Carnegie's pledge, a Cleveland Plain Dealer article pointed to the Cleveland Public Library Board of Trustees' plan to use part of the donation to relocate the West Side branch to the northwest corner of Pearl and Lorain Street (Avenue), where the old Pearl Street Market stood. The City of Cleveland was in the process of planning to construct a new West Side Market right across Pearl Street from old one, and the Library offered that, if the City would donate the old market property to it, the Library would expend $50,000 of the Carnegie funds to construct a new library building on the property that would feature a large auditorium for the public.

The Library's proposal to site the new West Side branch library across the street from where the new West Side Market was to be built drew an immediate and negative public response. At least four different groups of residents and/or business owners protested the proposal and recommended various other locations for the new branch library. One of these groups felt so strongly that, on June 8, 1903, two hundred of its members traveled downtown to Cleveland Public Library's main building, which then stood on the southeast corner of Wood (East 3rd) Street and Rockwell Street (Avenue). There they protested outside--while the Board held a meeting inside--each member wearing a silk badge that read: "Branch Library, Corner Clark Avenue and Lorain Street."

As a result of the widespread public opposition, the Library abandoned its Pearl Street market site proposal and instead referred the matter to a committee for additional study and recommendations. Nearly two years passed before the Library's Board of Trustees, after reviewing its committee's recommendations, decided in 1905 to site the new West Side branch library on Fulton Road (then, Rhodes Avenue), just north of Lorain Avenue. This was then a central location in a fast growing area of the West Side that was centered upon the Lorain Avenue commercial corridor. In a few years, the intersection of Lorain and Fulton would become known as Lorain-Fulton Square. The Board purchased three lots on Fulton, no more than 100 feet from Lorain, and was prepared to begin the construction process when, once again, the West Side public intervened.

In the same month that the Library completed the purchase of its lots on Fulton, the West Side Improvement Association (WSIA), an organization of business owners and other prominent West Side individuals, held a meeting at the Catholic Club, on Bridge Avenue just west of historic St. Patrick Catholic Church. Some 400 people, including Librarian William H. Brett, reportedly attended. There, a proposal was made for the City to purchase additional land on Fulton north of the lots that the Library had purchased; use the Library's lots to extend Kentucky (West 38th) Street from Bridge to Fulton; and then create a park in the resulting triangular-shaped piece of land where the new West Side branch could then be sited. Ward 3 Councilman Thomas Croke, in whose ward the library and park would be located, agreed to introduce a City Council resolution to direct the City administration to explore the feasibility and cost of such a plan.

Cleveland City Council adopted the WSIA park proposal resolution, and ultimately, it resulted in an additional two and one-half years of delay in the siting and building of the new West Side branch library. During that period, City Park Engineer William Stinchcomb, who later became known as the "Father of the Cleveland Metroparks," floated an idea of making the proposed library park a "civic center" where statues of prominent literary figures could be placed. He suggested that the Schiller-Goethe monument, which stood in the way of the soon-to-be-built Cleveland Museum of Art, could be moved from Wade Park to the new library park to represent Germany's contributions to world literature. Stinchcombs' proposal, a forerunner to the Cleveland Cultural Gardens, was never acted upon and the Schiller-Goethe monument was destined to remain where it was until it was relocated to the German Cultural Garden in 1929.

By 1907, the delay in planning and constructing the new West Side branch library was not the only problem facing the Library. It had exhausted nearly all of Andrew Carnegie's 1903 donation in building the first five of the proposed seven new branches, and now, moreover, there were substantial additional expenses projected to be incurred by the City and Library in purchasing the land needed for the library park, building the Kentucky Street extension, creating the park in which the library would be located, and then actually building the new branch. These expenses easily could have doomed the project. However, in a sign of how much he valued both the branch library project itself and Librarian Brett as a resource, Andrew Carnegie stepped in and made additional donations to ensure that the new West Side branch library would be built.

After learning from Brett that building the first five branches had exhausted the original donation, Carnegie agreed to donate an additional $123,000 to construct the last two branches--the new West Side Branch library and new South Branch library. In 1908, in order to ensure that there were sufficient funds to enable the City to purchase the land for the park and the Kentucky Street extension, he donated an additional $110,000. Without these last two donations, it is questionable whether the West Side branch library would ever have been built, let alone in the grand form of the building that sits on Fulton Road today. James Bertram, Andrew Carnegie's personal secretary, noted how extraordinary the first of these two additional donations were in a letter he wrote to the Library on July 2, 1907: "Mr. Carnegie congratulates Cleveland upon exceeding even Pittsburg in proportion to the amount of population, in Library appropriation, placing Cleveland first of all."

With the all-important land acquired, construction of the new West Side branch library (appropriately renamed Carnegie West in a nod to Carnegie's 1908 donation) began in the Fall of that year and was completed in the spring of 1910. Designed by New York architect Edward L. Tilton in a modified Renaissance style with classical elements, the new branch was built in a triangular shape, with a facade composed of red brick, limestone and terra cotta. It has banded and fluted columns and pilasters in the Ionic style. With an interior covering 25,000 square feet of space, Carnegie West was Cleveland's largest branch library building. It had weathered oak finish and walls adorned with carbon prints of famous pictures and noted buildings. A majority of the rooms also had plaster friezes. There were balconies in the children's and reference rooms. An auditorium in the basement seated 650 persons. The new library was dedicated and officially opened to the public in May. Several months later, library experts from the American Library Association visited Cleveland to see the new branch library. According to an article appearing in the Plain Dealer on July 29, 1910, they unanimously declared, "for general attractiveness, facilities for circulating books, up-to-date interior equipment, method of handling the books and the ability of those on the staff, the West Side institution, for a branch library, stood without a peer anywhere in the United States."

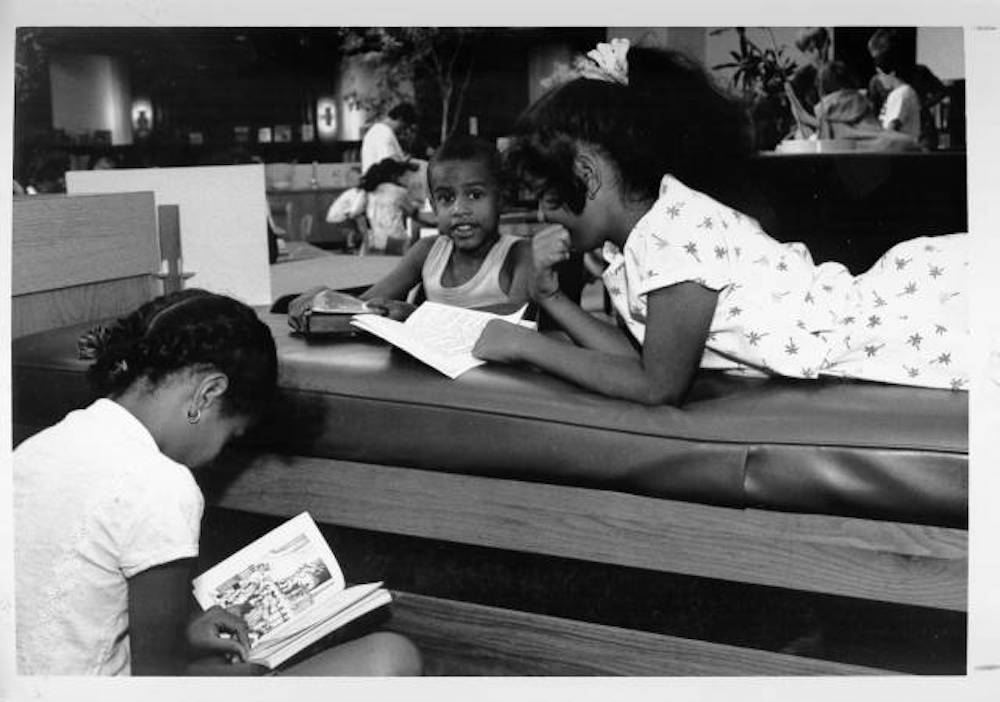

In the course of its long history, one of the library's most endearing traditions has been its service to the segment of the neighborhood population with the greatest educational needs, viz., immigrants and other non-English speakers. When the branch library opened in 1910, that group was largely composed of Hungarian immigrants who had been moving into the neighborhood since the late 19th century. Carnegie West staff welcomed them by providing books in their native language, sponsoring their cultural events at the library or in Library Park, and by offering classes in English. When World War I intervened and caused many Americans to question the loyalty of Hungarians and other recent immigrants from eastern and southern Europe, the Cleveland Public librarians, including those at Carnegie West, responded with their own version of "Americanization," which showed a respect for the culture, language and traditions of the newcomers and offered their services and materials to help them navigate their new life in this country.

In the second half of the 20th century, Puerto Ricans and other Spanish speaking people began to move into the Ohio City neighborhood, gradually replacing the Hungarian-Americans as the largest ethnic group of non-English speakers. Just as it had for Hungarian residents, Carnegie West provided books in their native language and offered the library as a place to hold cultural events. In 1992, when Carnegie West celebrated the 100th anniversary of the opening of the first West Side branch library, the celebration included a demonstration of traditional Hispanic and Hungarian dances.

As the library aged in the second half of the twentieth century and the population of the Ohio City neighborhood shrank, the Library Board of Trustees was forced to weigh whether to retain the large library building or tear it down and replace it with a smaller building "better sized" for the neighborhood. When this was proposed in 1979, West Side residents turned out in opposition to the proposal just as they had some seven decades earlier. Cleveland Public Library listened and decided instead to renovate and remodel the historic building, reducing its interior space in half, even though the cost of doing so was greater than that of constructing a smaller replacement. In the ensuing years, other major repairs and renovations have been made to the building, including the 2004 repainting of the interior walls to their original colors. Today, 113 years after it first opened to the public, Carnegie West remains an architectural jewel in the Lorain-Fulton area and an important civic and cultural center for the entire Ohio City neighborhood.

Images