The Cleveland Public Library comprises one of the largest collections in the United States: nearly ten million items. The Library’s two buildings on Superior Avenue (the main structure, 1925) and the Stokes Wing (1997) command an entire city block between East 3rd and East 6th Streets. The exceptional collection and iconic buildings demonstrate both the institution's importance as a symbol of democracy and—at a more pragmatic level—the library's popularity.

The development of the Cleveland Public Library mirrored a larger movement in the United States: merging practices from tax-funded school-district libraries with early circulating libraries that required fees or membership dues. Heavily laden in classist ideals of democracy, these early public libraries became increasingly popular in the last decade of the 19th century. The advancement of publicly funded libraries also was a response to rapid social changes—particularly industrialization and a tidal wave of immigrants. Thus public lending institutions focused largely on maintaining large collections of educational materials, even though limited operating hours and a closed-stack system limited their accessibility.

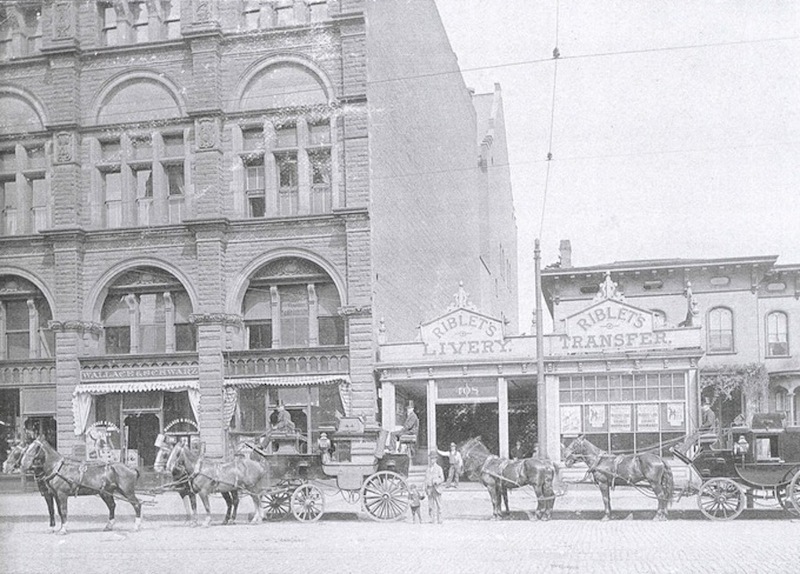

Cleveland's first public library was founded in 1869, following the passage of a law providing library funding as part of the Cleveland school system. Known until 1883 as the Public School Library, the new institution on the third floor of a building off West Superior Avenue was estimated to have 5,800 books on its opening day. Visitors to the 20 x 80-foot room had to submit their requests at a main counter. The item would then be retrieved from the stacks by an employee of the library. This system remained in place until 1884, when William Howard Brett was appointed librarian. Under Brett's direction, the institution became a model for progressive, service-oriented libraries throughout the United States, a fact that led to its popular nickname "The People's University."

The notion of accessibility lay at the core of Brett’s innovations. He made all materials in the adult sections available to the public. Cleveland Public Library also became the first large urban library to institute an open-shelf policy. In addition, Brett developed programs and collections for children, instituted a classification system to group books of similar subject matter, opened Cleveland's first branch libraries, created library stations throughout the city, expanded the collection of fiction, and created the city’s first stand-alone children's room. This trailblazing librarian helped secure both the land and funding for the Cleveland Public Library's permanent home in the city's emerging civic district east of Public Square.

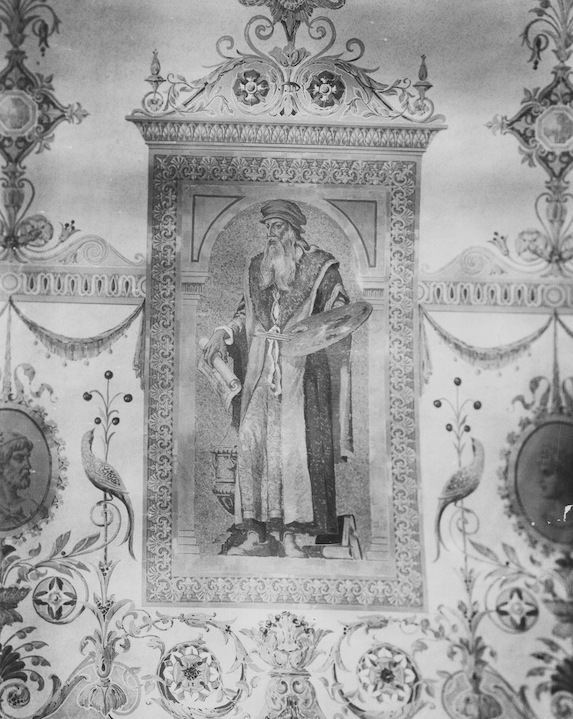

And what a home it is. Designed by the prominent architectural firm of Walker & Weeks, the five-story facility was completed in 1925 for about $5 million. It is one of six buildings conforming to the Group Plan, an ambitious 1903 city-planning scheme built around a massive three-segment public park (the Mall) northeast of Public Square. Like most of the Group Plan buildings, the library reflects a Beaux Arts, neoclassical design. Its interior was modeled in a Renaissance style, making ample use of Italian marble. Vaulted ceilings are adorned with paintings of mythological and historical figures, while grand staircases carved in Botticino marble and elaborately decorated passageways invite visitors to explore the library's various departments.

Library functions were sorely tested during the Great Depression, when restrictions on public taxation reduced funding to libraries. Salaries were reduced, staff was let go, and the acquisition of new materials dropped drastically, even as library usage increased by up to 20 percent. Fortunately, Franklin D. Roosevelt's Public Works programs included the Cleveland library: WPA employees made building repairs, cleaned, painted, and even copied musical scores. In the 1930s, the library also was a recipient of federally funded art. In addition to countless prints and paintings, three WPA murals adorn the main Library’s walls to this day. Six additional murals were painted for branch libraries.

The late 1990s were a busy and productive time for the Cleveland Library system. Massive renovations were made to the building. A second structure—named after former U.S. Congressman Louis Stokes—was built in 1997 on the former site of the Cleveland Plain Dealer which, since 1957 had been used by the library as an annex. Focused largely on science and technology, the Stokes Wing has 11 floors totaling 267,000 square feet and more than 30 miles of book shelves for a capacity of 1.3 million books.

The two buildings are connected by an underground corridor below the outdoor Eastman Reading Garden, named after Linda Anne Eastman (1867–1963), the first woman to head a major U.S. city library system and a pioneer in the modern library system. The garden that bears her name was designed by landscape architecture firm OLIN, and includes sculptures by Maya Lin and Tom Otterness. The garden provides space for concerts, garden shows, book displays, and public art exhibits. Think of it as the center of a cultural sandwich—part of a block-long demonstration of Cleveland’s prowess and historic leadership in the arts and humanities.

Today, the Cleveland Public Library operates 27 branches throughout the city, a mobile library, a Public Administration Library in City Hall, and the Ohio Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. Among the main facility’s special collections are the Mears and Murdock baseball collections, the Cleveland Theater collection, 130,000 volumes of children's material, a 74,000-volume rare book collection, 1.3 million photographs, and the John G. White Chess Collection—believed to be the largest and most comprehensive chess library in the world. In 2009, CPL became the first library in the United States to offer e-book downloads.

Video

Images