Fulton Road is one of seven streets that were originally designed to radiate from Franklin Circle in accordance with the 1836 subdivision plat created by Ohio City pioneer real estate developers Josiah Barber and Richard Lord. Starting at the Circle, it runs for one-half mile in a southwesterly direction, intersecting several grid streets at sharp angles, before terminating--at least until 1905--at Lorain Avenue (then, Lorain Street). It is unknown whether Barber or Lord envisioned it, but the original terminus of Fulton Road was destined to become one of the most commercially important corners on the west side of Cleveland in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Eighteen years after Barber and Lord recorded their 1836 subdivision plat, Ohio City was annexed to Cleveland, becoming that city's west side. At about the same time, German immigrants began arriving in Cleveland in large numbers and moving onto streets in the Barber and Lord and other residential subdivisions located on lands north and south of Lorain, and west of West 25th Street (then, Pearl Street). As the immigrant population swelled in these subdivisions, a neighborhood emerged and Lorain Street transformed into its commercial corridor. Retail merchants of German origin built and occupied store fronts along the street's north and south sides, and, before long, both sides of Lorain Street were lined with retail stores all the way to Cleveland's western corporation line which, in the post Civil War period, was just west of West 59th Street (then, Purdy Street).

A number of these early west side retail stores were built at or near corners of the intersection of Lorain with Fulton and nearby Willett Street, a north-south grid street which began on the south side of Lorain just across the street from Fulton Road's terminus. (In 1905, Willett Street would be renamed Fulton Road, creating the much longer version of the latter road that Clevelanders know today.) These two intersections (hereinafter, simply referred to as the Lorain-Fulton intersection) were from the start likely viewed by merchants as favorable places to conduct retail business. As noted above, the Lorain-Fulton intersection was just a half mile down Fulton from Franklin Circle, where the west side's elite were already beginning to build the mansions that would one day make Franklin Boulevard (then, "Franklin Street") the "West Side's Euclid Avenue." Moreover, the intersection was also just one-half mile down Lorain from the West Side Market, which had become, since it relocated to the northwest corner of Lorain and Pearl in 1859, a popular place where west siders gathered and shopped for their meat and produce.

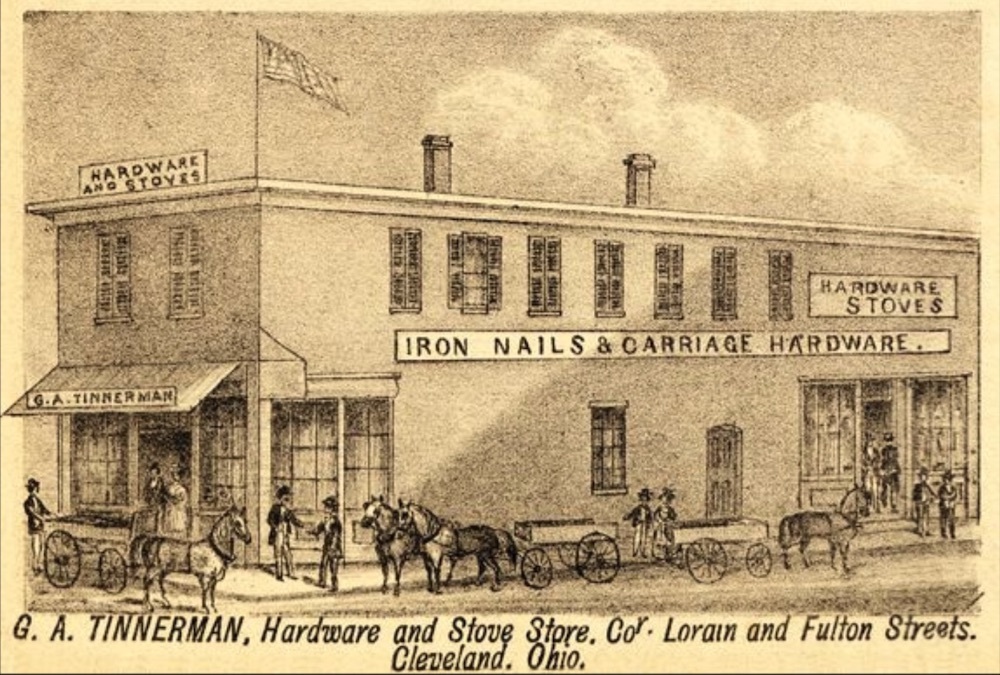

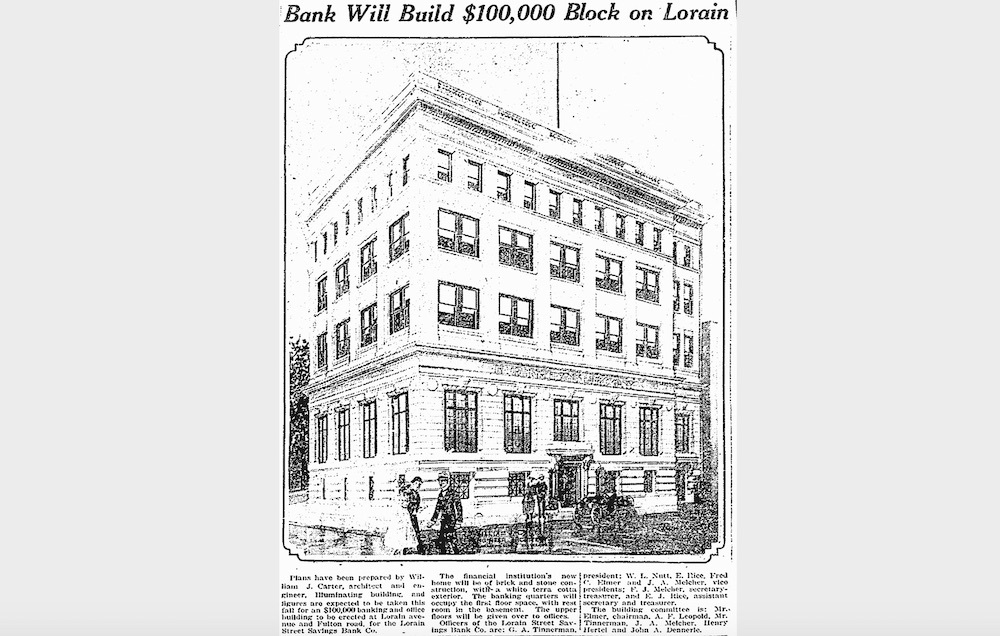

The early retail merchants who located their businesses at or near the Lorain-Fulton intersection included grocers, butchers, shoe makers, saloon keepers, tobacconists, bakers, confectioners, milliners and tailors, to name just a few. A survey of period directories suggests that business failures among these merchants were frequent and it wasn't unusual for a merchant to sell one type of product one year and then an entirely different one the next. Two of the early merchants who located at or near the intersection, however, are noteworthy for establishing retail businesses that thrived for decades. One was Henry Leopold, a German immigrant from Hanover, who, in 1859, opened up a store near the southeast corner of the intersection where he initially manufactured and sold furniture and caskets. Eventually, his company would leave the casket business and devote its full attention to making and selling furniture. Leopold's store was a neighborhood fixture until the 1940s when it relocated to Cleveland's West Park neighborhood and, after that, to the suburb of Brecksville where it is still in business today. The other notable early merchant at this intersection was George Tinnerman, a German immigrant from Bavaria, who opened a hardware and stove store on the northeast corner in 1868. Tinnerman later developed a steel range stove which became so popular that, after operating his retail business at the Lorain-Fulton intersection for almost four decades, he finally closed it in 1915 to focus exclusively on manufacturing steel range stoves at a factory he built on Fulton Road just south of the Lorain-Fulton intersection.

In 1879, the businesses of Henry Leopold, George Tinnerman and the other merchants engaged in the retail sale of products or services at or near the Lorain-Fulton intersection were boosted when the West Side Street Railway (WSSR), then controlled by Marcus Hanna, bested Tom Johnson's Brooklyn Street Railway and secured a license from Cleveland City Council to build and operate a new branch of the WSSR streetcar system on tracks which soon ran south on Fulton from Franklin Circle to Lorain and then west on Lorain Chestnut Ridge (today, West 73rd) Street. Later, that new branch was additionally connected to the WSSR main line by a separate track which ran from the Lorain-Fulton intersection to Pearl Street. As more and more streetcar riders hopped on, got off or waited for a transfer at the Lorain-Fulton intersection, the businesses of nearby merchants grew as evidenced by the construction of many larger and more grand commercial buildings at or near the intersection in the decades that followed.

In the early twentieth century, another change came to the Lorain-Fulton intersection that reflected its continued vitality and key location on Cleveland's west side. Between 1903 and 1905, the Cleveland Public Library, armed with a promise of funding from Andrew Carnegie, conducted a search for a site for its new West Side branch library. A number of sites at or near prominent West Side intersections were considered, including one at the intersection of Lorain and West 25th near the West Side Market and another at the junction of Lorain and Clark Avenues. The Board, however, ultimately chose a site on Fulton Road less than a tenth of a mile north of the Lorain-Fulton intersection. The new Carnegie West branch library opened in 1910. It was then, and still is today, the largest of Cleveland Public Library's branch libraries.

In the same year that the new library opened, the City of Cleveland, spurred by the example of New York City, began naming a number of its more notable diagonal intersections "squares." (For example, the diagonal intersection of Huron Road and Euclid Avenue in downtown Cleveland was named "Euclid Square" in1910. It was later renamed "Playhouse Square" in 1921 when theaters began to locate there.) While it is not known whether the City of Cleveland ever officially named it a square, the Lorain-Fulton intersection became popularly known on the West Side as "Lorain-Fulton Square" in this decade, likely as the result of a number of actions taken by merchants with stores located at or near the intersection. In 1914, a number of these merchants, including George Tinnerman and Henry Leopold's son August, formed the Lorain-Fulton Square Business Association to further their mutual business interests and promote the area as a great place for west siders, including those on west side street cars, to shop for all of their family and other needs. In 1915, the merchants sponsored a contest to create a slogan for their business area. The winning slogan was "The Hub of the West Side." The merchants later used that slogan repeatedly in "Opportunity Ads" that promoted their stores and advertised their "bargain" sales.

The 1920s opened with another sign of the continuing commercial vibrancy of the Lorain-Fulton intersection. On December 25,1921, John and Bertha Urbansky opened their beautiful new Lorain-Fulton Theater at 3321-3409 Lorain Avenue, adjacent to Leopold's four-story furniture store on the intersection's southeast corner. The theater seated 1,400 patrons; had a dance hall on the second floor; and had storefronts for retail businesses. In the years that followed, the intersection remained an active and busy commercial area, but as streetcars declined and automobile traffic increased, as upper- and middle-class residents (and the businesses that catered to them) moved to the suburbs, and as the city's deindustrialization began in the post World War II era, Lorain-Fulton Square began to lose many of its shoppers. By the 1950s, historic commercial buildings at or near the intersection were already beginning to show signs of deterioration and neglected maintenance. A number of them were torn down and replaced by parking lots, gas stations or fast-food restaurants which better served the needs of the more mobile--and more transient--population now frequenting Lorain-Fulton Square.

At least since 1993, when the Cleveland Landmarks Commission cataloged historic buildings on Lorain Avenue between West 32nd and West 58th Streets during the process that created the Lorain Avenue Commercial Historic District, the City has been aware of the extent of the deterioration and loss of historic buildings at or near Lorain-Fulton Square. Before Landmarks Commission intern Don Petit walked up and down Lorain Avenue in that year, snapping photos of the historic buildings, many historic buildings were already lost--burned down, torn down or perhaps blown down in the 1953 Tornado. The photos he took were part of a City effort to save the remaining historic buildings. Many of the buildings that were still standing at or near the intersection of Lorain and Fulton when Petit walked the area in 1993, no longer are. Lorain Fulton Square has become a very different place than it was one hundred or even thirty years ago.

While other prominent West Side intersections such as Detroit Avenue -West 25th Street and Lorain Avenue -West 25th Street have for decades garnered attention from redevelopers resulting in the preservation of a number of historic buildings in those areas being saved, Lorain-Fulton Square has not. In 2022, however, there is reason for hope as Lorain Avenue west of West 25th Street is beginning to get redevelopment attention. While little of that attention has yet come to Lorain-Fulton Square itself, it seems inevitable that it soon will. It would be fitting to honor the rich commercial history of this historic intersection with redevelopment that recalls and reflects some of the height, massing and location of significant historic buildings. This would seem to be good for business branding. It would also instill some pride in new business owners operating there, as well as new residents choosing to live there, as they came to learn that Lorain-Fulton Square was at one time, and for good reason, known as the "Hub of the West Side."

Images