On June 11, 1928, the Cleveland Plain Dealer ran a front page article criticizing the decision of Cleveland City Council to abandon the proposed extension of Chester Avenue to University Circle just months after recent construction had made it a continuous street from East Ninth to East 55th. The article's lengthy headline reflected both the paper's opposition to and its frustration with the decision: "$1,000,000 Spent On Chester--Why? Proposed Traffic Artery Now May Sink to Status of "White Elephant." After Two Years of Work, Councilmen Call City Project Dead." When you examine the long construction history of Cleveland's Chester Avenue, you can't help but at least empathize with the Plain Dealer. City Council's decision, however, turned out to be just another bump in the road of that long history.

The construction history of Chester Avenue dates back to the early nineteenth century when several residential streets named after trees were constructed off Erie (East Ninth) Street north of Euclid Street (Avenue). By the time legendary surveyor Ahaz Merchant drew his now famous map of Cleveland and its Environs in 1835, Chestnut Street, as Chester Avenue was originally called, already existed from Erie Street to Cleveland's eastern boundary (East 13th Street today). In 1859, several years after Cleveland had expanded that boundary by annexing the ten-acre lots to the east, the heirs of Samuel Dodge, a Cleveland pioneer and early Euclid Avenue resident, extended Chestnut Street to Dodge Street (East 17th Street) in order to provide access to a new residential subdivision they were developing on the northern section of their father's land, near Superior Street (Avenue). Later in the second half of the nineteenth century, two more streets were laid out east of the terminus of Chestnut Street that would one day become parts of Chester Avenue. In 1874, Windsor Street was constructed from Willson Avenue (East 55th Street) to Case Avenue (East 40th Street) and, in 1890, East Chestnut Street—it was so named at the insistence of Cleveland Mayor George Gardner to distinguish it from Chestnut Street—was constructed from North Perry (East 21st) Street to Sterling Avenue (East 30th Street). Thus, by 1890, segments of future Chester Avenue existed from today's East Ninth to East 17th, from East 21st to East 30th, and from East 40th to East 55th.

In the 1890s, during the era of the City Beautiful movement, Cleveland 's Park Commission and a number of civic leaders, including John D. Rockefeller, began actively planning for the development of an extensive east side park system, one that would eventually include, among others, Gordon, Rockefeller and Wade Parks, all part of the City of Cleveland as the result of the annexation of East Cleveland Village in 1872. The plan, as originally envisioned, included transforming grand residential Euclid Avenue into a park boulevard that would lead directly into that east side park system. In order to create that boulevard, the Commission proposed to remove streetcar tracks and other traffic fixtures from Euclid Avenue (from Case Avenue (East 40th Street) eastward), and relocate them to two east-west thoroughfares to be built to the north and south of Euclid Avenue. Members of the Commission believed that building these new thoroughfares to the City's "east end," as the area was then known, was necessary to insure that ordinary Clevelanders—not just the city's elite—would have direct and easy access to the new park system whether they took a streetcar, drove a carriage or rode there on the latest craze, the "safety" bicycle. From the start, an extension of Chestnut Street was considered by many to be the most viable route for all or at least part of the northern thoroughfare, but there were other streets in contention too, including Hough, Payne, Perkins and Wade Park Avenues. Discussions of whether and how far Chestnut Street (later, Chester Avenue) should be extended would continue on and off during this decade and the next four, but, prior to 1919, no extensions were constructed. Before 1912, this was largely because city officials were not able to secure state approval for financing such a project. After 1912, following the enactment of the Home Rule Amendment to the Ohio Constitution and the passage of Cleveland's first city charter, the project ran into a different type of financial roadblock when Cleveland voters rejected several road construction bond issues, many considering such projects to only benefit people who lived in the suburbs. During the years 1910 to 1915, while the fate of its extension lay in planning limbo, Chester Avenue from East 21st to East 28th Street, lying directly north of Millionaires' Row, was used by Cleveland's elite during the winter months as a race track for competitive sleigh rides. It became known during this period, somewhat ironically, as the Chester Speedway.

Planning for the Chester Avenue extension and other Cleveland road projects took a more professional turn when the City Plan Commission was established in 1915 and a platting engineer hired three years later in 1918. By this time, Cleveland was fast on its way to becoming the fifth most populous city in the United States, and its streets were just as fast becoming crowded with streetcars and automobiles. In 1919, the Plan Commission began a study of the City's streets and traffic, which resulted in the Commission's Thoroughfare Plan of 1921. It proposed to address the City's traffic problems by widening 180 miles of streets and opening or extending another 30 miles of streets. While the study was still underway, the City undertook to construct a first extension of Chester Avenue, from East 17th Street to East 21st Street, to divert automobile traffic off Euclid Avenue and onto Chestnut/Chester Avenue. It had an eighty-six foot wide right-of-way (ROW) with four lanes for traffic, and, when completed in 1921, it provided Cleveland motorists with a continuous roadway out of downtown from East Ninth to East 30th Street. Businessmen recognizing that Chester Avenue would soon become a popular route for motorists, began locating gas stations, tire stores, and other automotive service shops on Chester between East 21st and East 30th Street, even before the new extension was completed. Soon, the former Chester Speedway acquired a new nickname: Automobile Row.

In 1927, a second extension of Chester Avenue, from East 30th to East 40th Street was completed, connecting it to the soon to be formerly named Windsor Avenue and making Chester Avenue a continuous roadway from East Ninth Street to East 55th Street. In early 1928, when a third extension, from Euclid Avenue across East Boulevard to East 107th Street, was underway, the expectation of many in the city, including the editors of the Plain Dealer, was that Chester Avenue at East 55 Street would soon be extended to University Circle, but instead, as noted above, in June of that year Cleveland City Council announced that it was abandoning the rest of the project. While the Plain Dealer jeered the announcement, City Council's decision in retrospect was understandable. In that decade all road projects in Cleveland were funded entirely by the City and throughout the decade of the 1920s it had been a struggle for the City to find sufficient funding for both land acquisition and the road construction itself. The land acquisition and construction delays which routinely followed as the City placed bond issues on the ballot or attempted to find funding elsewhere often resulted in the City ultimately paying prohibitively high costs to complete its road projects, especially in a time when Cleveland land values were on the rise. One notable example of this arose in 1928. The City was without sufficient funds to purchase a vacant lot on East 97th Street that lay in the path of a proposed extension of Chester Avenue extension west from East 107th Street. Electing to stall for time, it issued an order denying the property owner a building permit to build on the land. The owner went to court, won, and then erected on the lot the four-story, 58-suite Traybird apartment building. Three years later, in 1931, when the city had funding available to purchase the land for the extension, it had to pay the owner four times what it would have paid him in 1928. Moreover, even after the owner was paid, he delayed three additional years moving the mammoth building--believed to be the largest building moved to date in Cleveland--to what would soon be the southeast corner of East 97th and Chester Avenue, costing the City more time and dollars.

The City's challenge of financing road improvements improved markedly in the 1930s when Cuyahoga County agreed to partner with the City in the funding of a number of the more important projects in the Thoroughfare Plan, including the Chester Avenue (now US Route 322) extension to University Circle. With the City responsible for land acquisition and the County for construction costs, three additional sections of the Chester Avenue extension were constructed during the 1930s, some with the help of Works Progress Administration (WPA) labor. In addition, several older sections of the Chester Avenue ROW were widened during this period from 60 and 70 feet to 86 feet to match newer sections constructed since the inception of the Thoroughfare Plan. The first joint project between the County and the City was the completion of the extension from Euclid Avenue west to East 107th in 1930. The financial impact of the Great Depression on the City and County delayed the next extension, from East 107th Street to East 97th Street, which was not completed until 1935. A third and smaller extension from East 97th to East 93 Street, which had been urged by local merchants and sponsored by then Ward 10 Councilman Ernest J. Bohn, was completed in 1939. With the completion of these three new sections of roadway, Chester Avenue was now a continuous roadway east from East Ninth Street to East 55th Street and west from Euclid Avenue, across East Boulevard, to East 93rd Street. All that remained to be done to complete the long envisioned northern thoroughfare from downtown to University Circle was to construct a final section from East 55th Street to East 93rd Street. Even though a bond issue that would have provided for land acquisition for the final section was passed in 1941, America's entry into World War II later that year, and then a postwar housing shortage that followed, put a halt to that land acquisition.

Planning for the roadway, however, continued and was expanded to include a new financing partner in the project, the State of Ohio, as well as two new planning bodies. Agreements between the State and Cuyahoga County provided for the County to pay land acquisition costs and the State to pay road construction costs with state and federal funds. Much of the planning for the extension during this period was conducted by Cleveland's new Planning Commission, which came into existence in 1942 following the voters' approval of a new City Charter. The State, County and City also received planning assistance during this period, and earlier, from the Regional Association of Cleveland (RA), a private nonprofit organization incorporated in 1937 by Cleveland Councilman Ernest J. Bohn. According to a January 14, 1967, Plain Dealer article, the RA was established "to study, thoroughly and scientifically, the means by which property values may be maintained and enhanced in Greater Cleveland." The new organization was headed by Abram Garfield, an architect, son of the former United States president and former Chair of the City's Plan Commission. Among the planning recommendations that the RA made to the City in the late 1930s was one to create a system of freeways in and out of, and around, Cleveland that would improve the flow of automobile traffic. The freeways proposed in, and eventually built from, this plan included the Willow Freeway, the Lakeland Freeway, the Innerbelt, and the Chester Avenue Extension, which was sometimes referred to as the "Chester Freeway," but more often as a "semi-freeway." Bohn himself, who had decided not to run for re-election to City Council in 1940 in order to devote more time to his work in public housing, became involved in the planning of this freeway system when he was appointed the first chair of the new City Planning Commission in 1942. There, he made an effort to ensure that the proposed new Chester Freeway, routed through the Hough neighborhood which he once represented as a councilman, was designed as a divided highway with plantings and other buffers sufficient to protect residents living near it.

In 1948, after the postwar housing shortages in Cleveland had abated, the State authorized Cuyahoga County to proceed with the Chester Freeway. Land acquisition was completed that same year and construction of the roadway—with a 150-foot-wide ROW and six lanes for traffic—was completed in 1949. On October 23, 1949, the new Chester Avenue extension was opened with a ribbon-cutting ceremony attended by Governor Frank Lausche and Cleveland Mayor Thomas Burke, and a large parade that marched up and down the City's new "freeway." Chester Avenue had now been extended all the way from East Ninth Street to University Circle, as envisioned by city officials in the nineteenth century. However, because it was six lanes only from East 55th to East 93rd Street, severe traffic bottlenecks soon developed on the road to the east and west this section of the road during rush hour. Resolving this traffic problem would require widening those other sections of Chester Avenue, primarily between East 13th and East 55th Streets, which included rebuilding the Conrail Bridge just west of East 55th, and from East 93rd Street to Euclid Avenue, which included building two one-way streets from East 107th Street to Euclid Avenue. Consistent with the long construction history of this road, it took the City another three decades to complete these widenings. The last of them—from East 30th to East 55th Streets—was not completed until 1979. It was only then that one could finally say that the City, with assistance from Cuyahoga County and the State of Ohio, had finally completed the northern thoroughfare from Downtown to University Circle that had been first imagined during the City Beautiful Movement nearly nine decades earlier.

Images

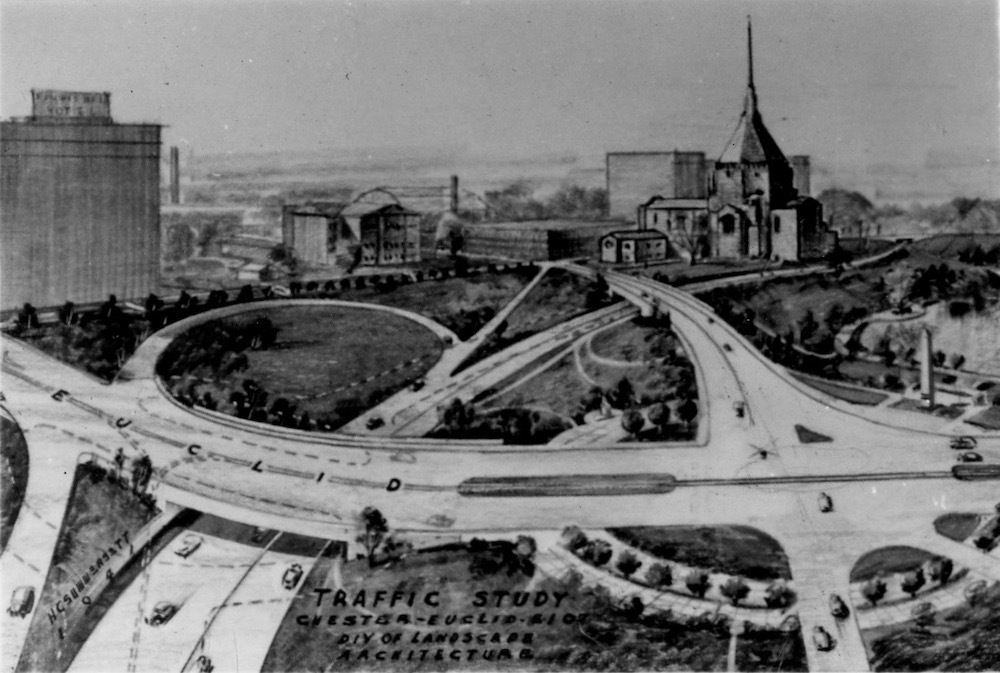

This aerial photograph taken in 1957 shows the recently completed two separated one-way Chester Avenues through University Circle. Source: Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections