Allen-Sullivan House

A Largely Forgotten (and now Razed) Grand Euclid Avenue House

It is one of the last grand houses still standing on Euclid Avenue, once described as the most beautiful residential street in the world. And yet, inexplicably, this house has not been designated as an historic landmark, has not been put to any use for nearly two decades, and its chances for long-term survival in the redevelopment of Cleveland's Midtown Corridor, at this time, do not seem very promising.

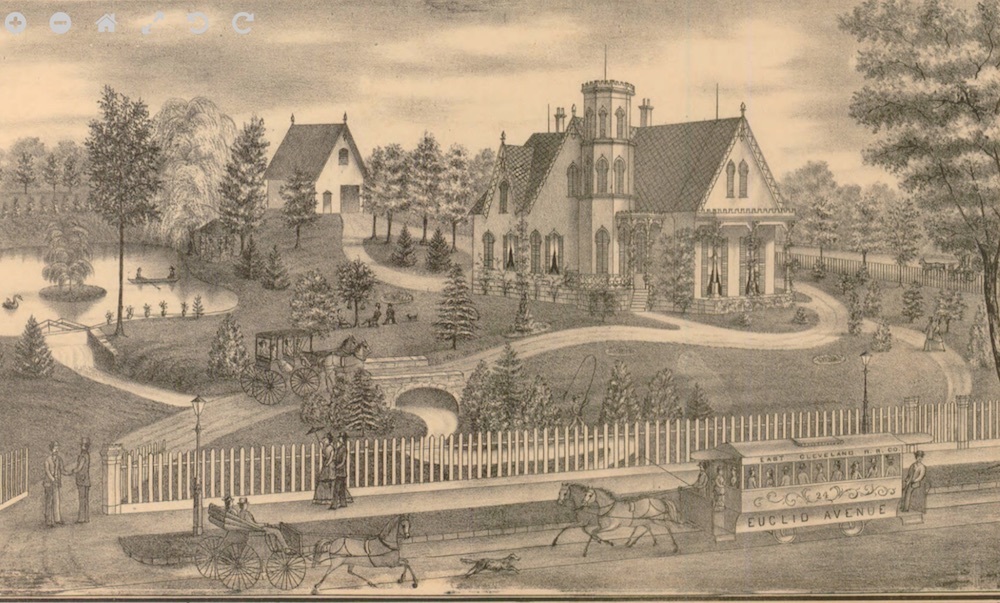

In the late nineteenth century, Cleveland's Euclid Avenue was considered by travel writers to be one of the most beautiful residential streets in the world, compared favorably to the grandest avenues in Europe. At the height of its grandeur, nearly 300 majestic homes graced its north and south sides from East 9th Street to East 90th Street. Only a handful--six or seven depending on your count--of those nearly 300 houses are still standing today. The Allen-Sullivan House (more commonly, but erroneously known as the Hall-Sullivan House--no one named Hall ever owned or occupied the house) at 7218 Euclid Avenue is one of them. And it is also the one most threatened by demolition.

Richard N. Allen (1827-1890) was a railroad engineer who invented the paper car wheel, which dampened wheel noise and vibrations, revolutionizing railroad passenger travel in the nineteenth century. The Massachusetts native, who had lived in Cleveland for a short period in the 1860s, returned to the city in 1881 after opening a factory near the Pullman Company's factory complex in Chicago. He did not move back because Cleveland was close to that factory. It was not. However, he may very well have decided to return because Euclid Avenue was here. It was then home to most of the richest men in America, and, as a result of his business successes, Allen, the former railroad engineer, was now a very rich man.

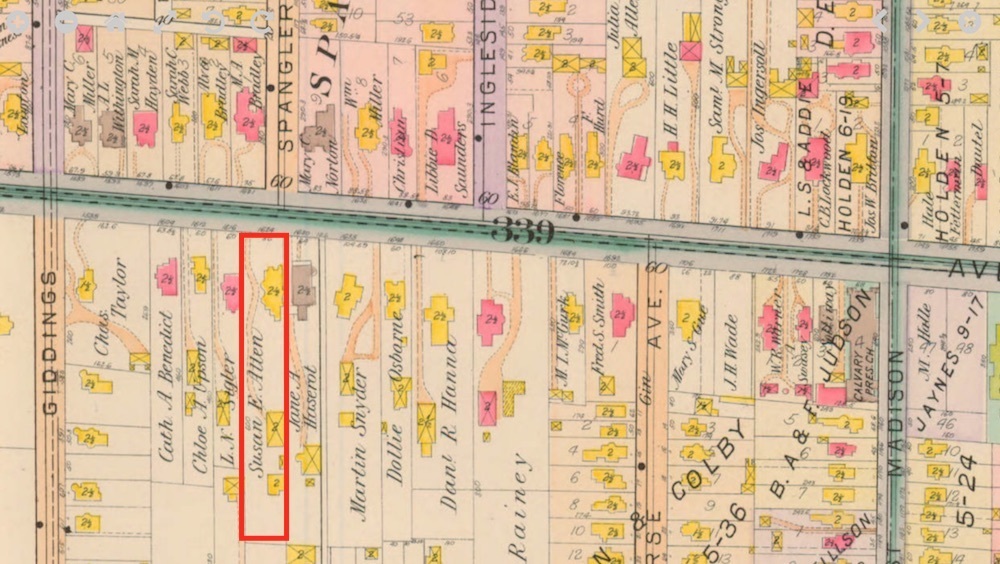

Allen and his wife Susan purchased a house on Euclid Avenue that had been owned by Ephraim J. Estep, a prominent Cleveland attorney. The house, likely built in the 1850s by one of the founders of the Joseph & Feiss Company, was located on the south side of the Avenue, just a few houses from Giddings Avenue (East 71st Street). While Euclid Avenue from Giddings to East Madison (East 79th Street) was not as grand and desirable a neighborhood as the more famous section between East 22nd and East 40th Streets, which in the early twentieth century became known as "Millionaires' Row," it was still a very grand and desirable place to locate indeed. Among the Allens' new neighbors were Morris A. Bradley (7217), heir to a shipping fortune and the father of future Cleveland Indians owner Alva Bradley; William J. Rainey (7418), said to be the largest coal and coke operator in the United States; Hiram Haydn (7119), pastor of the Old Stone Church and future President of Western Reserve University; Dr. Hiram Little (7615), a physician who became one of Cleveland's largest real estate developers; Edward Lewis (7706), a co-founder of Otis Steel Company and later a principal of Lake Erie Iron Company; and J. H. Thorp (7801), vice-president of Forest City Varnish Company.

In 1881, when the Allens arrived on the Avenue, there were nineteen grand houses on Euclid between East 71st and East 79th Streets. Less than two decades later that number had increased to thirty-six as several large lots were subdivided and sold to make more land available on the Avenue for Cleveland elites. Many of those new houses going up in those ensuing decades were of Queen Anne design, the most popular architectural style of the period. Queen Anne design is characterized, according to "A Field Guide to American Houses," by a "steeply pitched roof of irregular shape, usually with a dominant front-facing gable; patterned shingles, cutaway bay windows, and other devices used to avoid a smooth-walled appearance; and an asymmetrical facade with partial or full-width porch which is usually one story high and extended along one or both side walls."

Perhaps simply to keep up with the Joneses, Richard and Susan Allen tore down the old Estep House in 1887 and built in its place a new three-story Queen Anne house. According to local architectural historian Craig Bobby, this house, with approximately 9,000 square feet of living area, might be viewed today as "subdued" compared to other Queen Anne Houses that were built on Euclid Avenue in this period, but its massing is "robust." The house's boldest architectural feature is "an atypically wide, off-center bay . . . that rises up onto the roof, nearly becoming a turret." The house also features a true turret on the east end of its front facade, which is deemphasized by a front porch which embraces the off-center bay, and bay windows on its east and west sides.

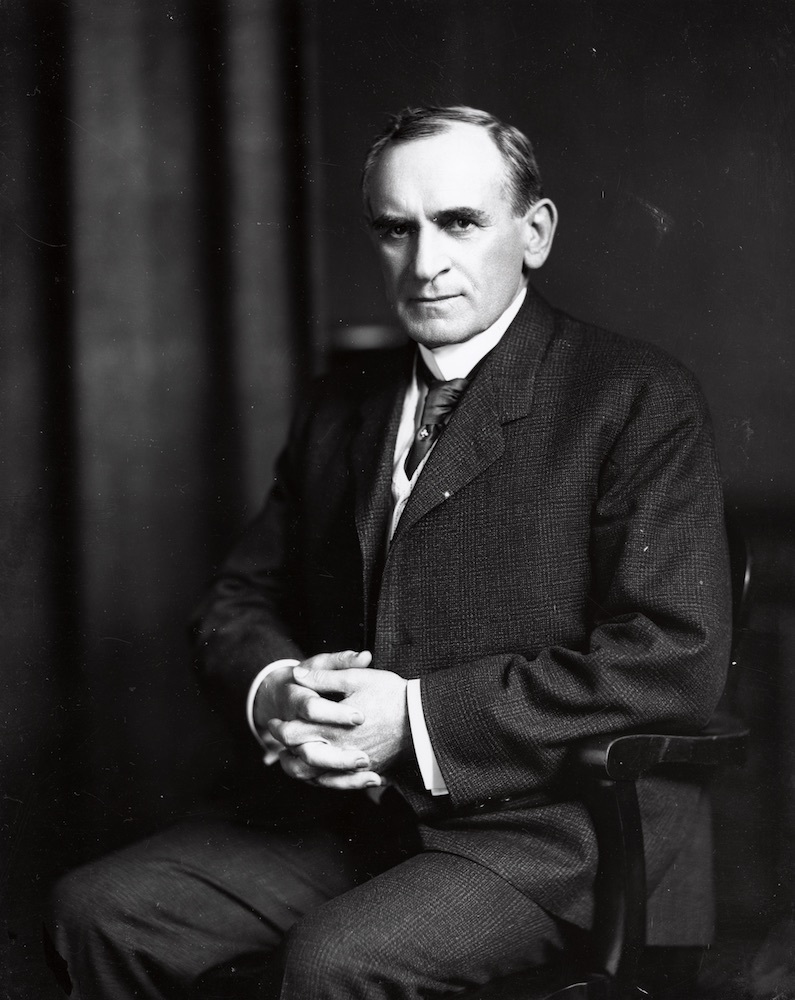

Richard Allen did not live very long after his mansion was completed. He died suddenly in 1890 at the age of 63. His widow Susan lived in the house until 1898, when she decided to move back to their native Massachusetts. The house was then sold to Jeremiah J. Sullivan, a prominent Cleveland banker. Sullivan, an Irish immigrant who moved to Cleveland in the early 1890s, was the founder of Central National Bank, which was one of Cleveland's largest banks in the twentieth century. In 1968, it erected the Central National Bank Building on the southwest corner of East Ninth and Superior. The 23-story building--today known as the AmTrust Financial Building--was at the time the fifth tallest building in downtown Cleveland.

When the Sullivan family moved onto Euclid Avenue in 1898, the Avenue was at its peak of wealth and elegance. Joining the Sullivan family as new residents of the East 71st-East 79th section of the grand Avenue in this decade were other prominent Clevelanders, including Dan Hanna (7404), the son of iron magnate and presidential kingmaker Marcus Hanna, and the future owner and publisher of the Cleveland Leader and the Cleveland News; David Z. Norton (7301), a Cleveland banker and principal of Oglebay Norton & Co., a large iron ore mining and shipping company; and Worchester Warner (7720) and Ambrose Swaney (7808), founders of machine and tool industrial giant, Warner and Swasey, and also life-long friends who built their Euclid Avenue houses next door to each other, just west of East 79th Street. These families were all witnesses not only to the zenith of the Avenue, but also to the beginning of its decline as a grand residential street. By the time the Sullivan family moved out of their house in 1923 shortly after Jeremiah's death, Cleveland's elite were already fleeing the Avenue, as a result, according to Euclid Avenue historian Jan Cigliano, of encroaching commercial businesses, the running of streetcars up and down Euclid Avenue, and a growing nearby African-American ghetto. By 1930, only two elite families still resided on the section of Euclid Avenue between East 71st and East 79th--octogenarian Ambrose Swasey, who lived in his house until his death in 1937, and the son of David Z. Norton, who left the family's Avenue mansion for Cleveland Heights in 1939.

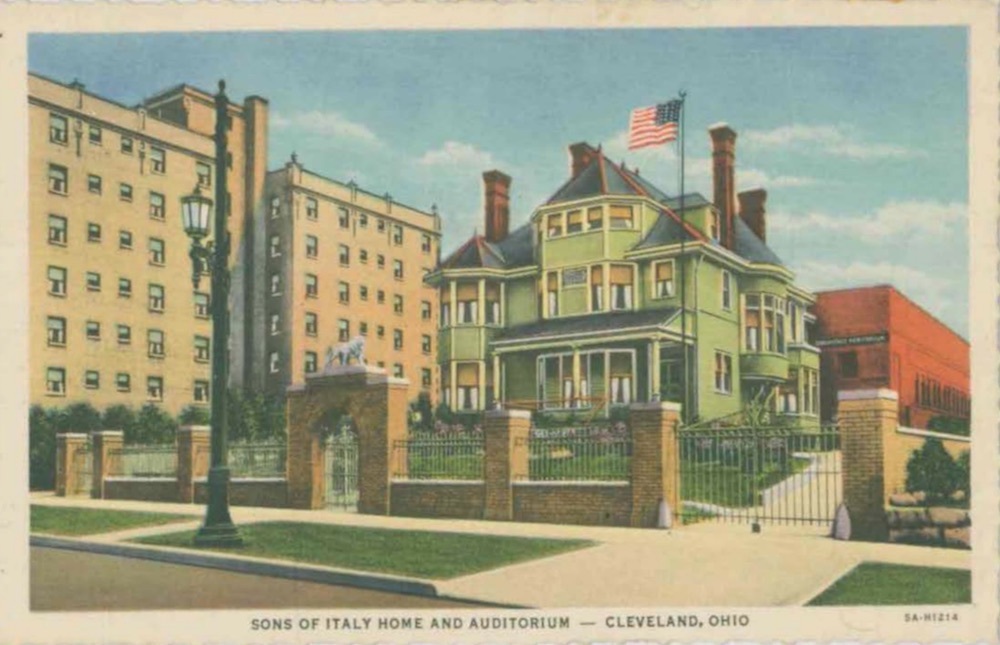

As Euclid Avenue declined as a residential street in the twentieth century, many of its grand houses were torn down, but others were put to different uses, sometimes commercial, sometimes multi-family, and sometimes institutional. The Allen-Sullivan House was one of those put to other use. After the departure of the Sullivan family, it first served, from 1923 to 1931, as an upscale furniture store known as The Josephine Shop. Then, in 1934, during the Great Depression, the house was purchased by the The Grand Lodge of Ohio, Order Sons of Italy (SOI) in America, an Italian-American fraternal organization. The SOI made it their Ohio Grand Lodge, adding an auditorium onto the rear of the house. On June 2, 1935, the organization held a dedication ceremony on the site, attended by many local, state and foreign dignitaries, including the Italian ambassador. It was the first time that an ambassador from Italy had visited the State of Ohio.

The SOI occupied the Allen-Sullivan House until 1946 when it sold it to the American Society of Heating and Ventilating Engineers (today known as ASHRAE--the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers). ASHRAE opened a national research laboratory on the site, operating it there from 1946 until 1961, when the laboratory closed. The property was then sold in 1964 to Mary Fisco, spouse of Benjamin Fisco, an Italian immigrant who restored the house to its condition existing during the period when it was owned by the Sons of Italy. Fisco operated a party center there known for years as the Coliseum (or Colosseum) Party Center. The party center closed in the late 1990s, several years after the death of Benjamin Fisco.

Since the year 2000, according to City of Cleveland officials and others, the house has been vacant except for an onsite caretaker. In that same period, a new owner purchased and assembled five sublots on and off Euclid Avenue near East 71st Street, including that upon which the Allen-Sullivan House sits. According to officials at MidTown Cleveland, Inc., the owner of those properties has listed them for sale with an asking price of $3 million. Given this owner's desire to sell, and the City of Cleveland's desire to continue redevelopment of its Midtown Corridor along Euclid Avenue, the future of the Allen-Sullivan House is precarious and it might not avoid demolition without an effort on the part of the City and/or the future developer to save it.

Meanwhile, ASHRAE has been waging a campaign since 2017 to have an Ohio historical marker placed in front of the Allen-Sullivan House to commemorate the national research laboratory that its organization operated there from 1946 to 1961. When you consider all the history that was made at this, the last-standing Queen Anne-style house on the once grand residential Euclid Avenue, an historical marker alone is not enough. The grand house itself should be saved too.

UPDATE: On June 21, 2021, time ran out for the Allen-Sullivan House. No savior was found. The house was torn down to make room for a city-approved apartment complex.

Images