Karamu House, originally the Playhouse Settlement, is the nation's oldest African American theater. Its development reflected its members' experiences not only in the segregated city from which it grew but also at a rustic retreat hidden away in Brecksville Reservation.

Since the establishment of the Cleveland Metroparks in 1917, many a sojourn in the wilderness has been highlighted by the warmth, flickering light, and crackles of a campfire. As recounted by founding co-director of Karamu House, Rowena Woodham Jelliffe, the impromptu exhibition was credited as the inspiration for the institution's acclaimed modern dance program:

I… remember one night when youngsters who had been toasting marshmallows moved back in the meadow behind the circle where people were sitting, and did this very interesting, exciting dance in the dark – with their glowing sticks outlining what their hands and bodies were doing… After this one night… the thing that was said was "Tomorrow, let's meet on the plateau and do these same things and see what they look like in daylight."

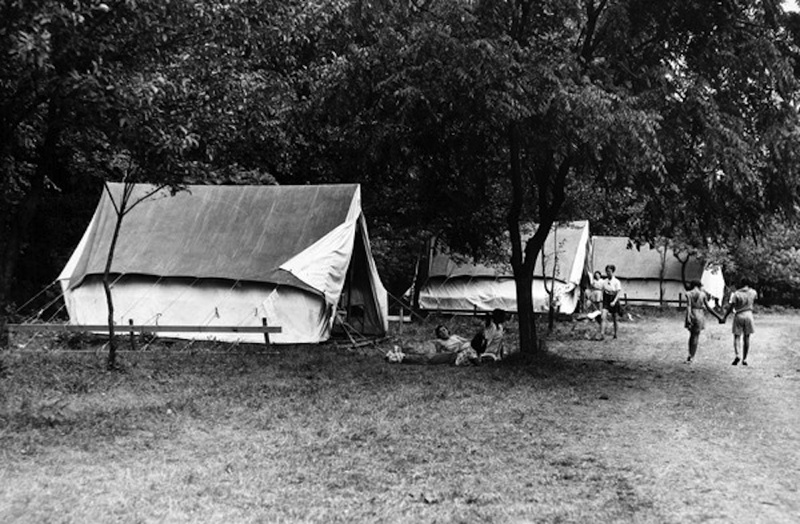

The evenings spent around the fire at the annual Karamu House summer camp in Cleveland Metropolitan Park District's Brecksville Reservation provided camp-goers more than burnt treats and a chance to wield flaming swords. As an extension of the settlement house, campers could partake in variety of educational classes including nature study, First Aid, sex education, music, crafts, and dramatic arts. Days were spent building boats, swimming, hiking, learning camp songs, and identifying plants, animals and rocks. The camper's activities were supplemented with ample portions of food, exercise and rest. These excursions into nature embodied the missions of the Cleveland's settlement houses and Park Board. The natural world was believed to offer an environment that could stimulate minds and promote good health in urban dwellers, as well as inspire morality, hope, imagination and calmness.

Health, calmness and hope were often in short supply for Clevelanders crowded into the confines of the city's ethnically and racially segregated neighborhoods. The settlement house movement took hold in Cleveland at the turn of the century to address problems that accompanied the rise of industry and urbanization. Progressive reformers worked within neighborhoods to provide educational and charitable resources to the community, and battled against substandard living and working conditions, poverty, and disease. By 1910, private philanthropic organizations financed ten settlement houses in Cleveland.

Social reformers were especially keen on transplanting city children into rural-esque environments as a means to promote physical and spiritual renewal. Romanticized ideals of nature were pitted as an antithesis to the city and its corruptive influence. Goodrich Social Settlement, Hiram House, and the Salvation Army were among the many benevolent institutions with camps scattered around the outskirts of Cleveland in the early 1900s.

The origins of the Karamu House and its summer camp reach back to this Progressive era social settlement movement. The Men's Club of the prosperous Second Presbyterian Church conceived the relief project in 1915. Located at E. 30th Street and Prospect Avenue, the church group wished to provide services to an adjacent neighborhood devoid of recreational and welfare organizations. Drawn to the socially progressive reputation of Oberlin College, the Men's Club presented alumnus Russell and Rowena Woodham Jelliffe the opportunity to develop and lead their relief effort. The young couple had recently finished graduate school at the University of Chicago, where they performed field work at the Chicago Commons and Hull House social settlements. Two homes were acquired near Central Avenue on East 38th Street; one served as the residence of the Jelliffes, and the other as a base for settlement operations.

This east-side community was undergoing a dramatic change at the time. German, Austrian and Jewish residents were moving away en-mass, succeeded by working class Slavic, Italian and African American settlers enticed by the temporary availability of war-time factory work. The demographic shift escalated just as the settlement house took root in the community. Following 1917, African Americans emigrants from the South flooded into the neighborhood. As one of the few refuges available to these settlers within an increasingly segregated city, overcrowding and poverty quickly followed. Multiple families commonly shared cramped living spaces, while unemployment, crime, discrimination, racial tension, and inadequate sanitation presented challenges to the area's newest residents.

Fashioned after similar Progressive era welfare agencies, the church-sponsored agency provided a variety of educational classes, social services and recreational actives to the surrounding community. As the only integrated settlement house in Cleveland, it quickly became a bustling center of the neighborhood. The home hosted popular lawn fetes, a milk station, basketball and football games, and Friday night dances. Reading and game rooms were opened to residents, and instruction was provided in topics such as citizenship, cooking, shopping, and using street car services. As time passed, the Jelliffes veered from traditional settlement-style charitable actives and directed their efforts on providing educational and cultural opportunities to the community. Sponsorial ties to the Second Presbyterian Church were cut, and the Playhouse Settlement of the Neighborhood Association was incorporated in 1919.

This transition from a settlement house to a neighborhood association, and the creation of its summer camp, was facilitated by a change in the way relief was subsidized in Cleveland. Previously, most charitable institutions relied on the direct philanthropy of Cleveland's prominent citizenry. During the second decade of the 1900s, community fund drives garnered popular favor. These relief organizations aggregated donations, and disbursed funding to vetted charitable groups. The newly established Playhouse Settlement fell under the umbrella of relief efforts sponsored by the Welfare Federation of Cleveland, and was financially backed by contributions to its Community Fund. The organized model for charity both simplified and promoted relationships between Federation committees and civic agencies.

A long-standing collaboration between the Cleveland Welfare Federation and Cleveland Metropolitan Park Board began in 1923. Brought together by a shared belief that nature provided a necessary counter weight to urban ills, sections of newly acquired park grounds were opened to social organizations for camping, education and recreation. The Welfare Federation handled applications for permits, coordinated resources, evaluated staff, and monitored the safety of camp facilities.

The Jelliffes wasted no time in taking advantage of the new partnership. On June 25, Playhouse Settlement opened Chippewa Valley Camp in Brecksville Reservation along River Road and Chippewa Creek. Brecksville Reservation remained the vacation grounds of Playhouse Settlement — later renamed Karamu House — until the camp closed in 1947.

The rustic retreat presented thousands of children a chance to explore and study nature in the Cleveland Metroparks, and was one of only a few summer camps in the Cleveland area available to the city's growing African American population. Just as a moonlit campfire dance helped guide the trajectory of cultural programming at Karamu House, the collaboration between the Park Board and community agencies to open summer camps during the early 1920s blazed a path for promoting educational and recreational programming in the Cleveland Metropolitan Park District during the next half century.

Images