Clement and Katherine Folkman, immigrants from Eastern Europe, probably didn't know much, if any, of the history of the house at 4206 Franklin when they purchased it in 1923. So they, and their son Clement Jr. proceeded to make their own history there.

The house at 4206 Franklin Boulevard is one of only a few Second Empire style houses on Franklin Boulevard. It has approximately 3,000 square feet of living area and is notable for its hexagonal mansard roof, decorative window hoods and wrap-around single-story covered front porch. The house was built in 1866 and, while the name of the contractor who actually built it is unknown, it may have been Ferdinand Dreier (Dryer), a German immigrant and house carpenter by trade. Dreier built a number of houses on or near Franklin Boulevard in the late 1860s, including a somewhat similar Second Empire style house almost directly across the street at 4211 Franklin.

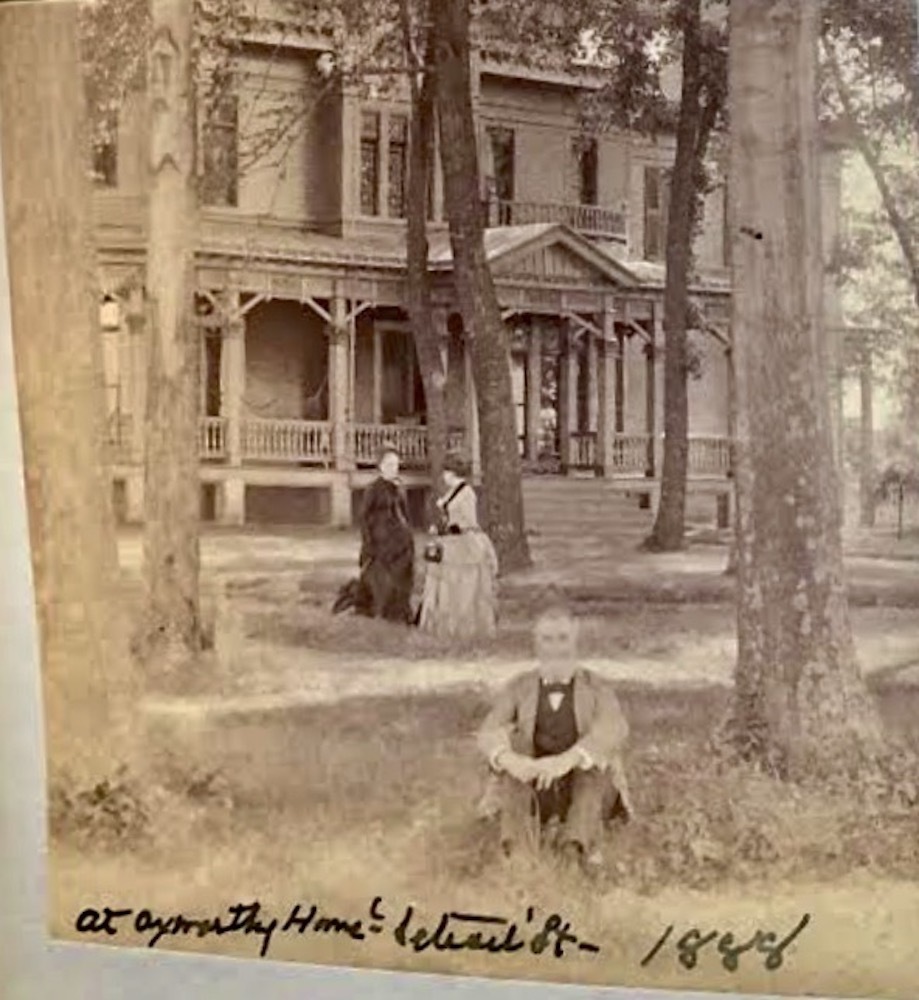

According to National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) records of the Franklin Boulevard Historic District, the house at 4206 Franklin is named for Thomas Axworthy, a nineteenth century coal merchant, who purchased it in 1873. Its original owner was Atherton Curtis, a liquor dealer, whose family only lived in the house for a year or so before moving to Huron County, Ohio. The family then rented the house out to tenants for several years before selling it to Axworthy, who lived in the house with his wife Rebecca and their three daughters for more than a decade.

Thomas Axworthy was an interesting figure who left his mark on Cleveland city government, although not in the way you might think. An English immigrant, Axworthy became involved in Cleveland politics in the 1870s, serving in that decade as a city fire commissioner as well as president of the "West Side Democracy," a political club for Democrats living west of the Cuyahoga River. In 1883, while his star was still rising, Axworthy was considered to be a likely candidate for city mayor, but he ran instead for city treasurer and was elected in a close race. He was re-elected to the office in 1885 and again in 1887. By the time he was re-elected the second time, he had already sold the house at 4206 Franklin, moving, like many other Franklin Boulevard residents during this period, to the city's far west end. There, he built a grand house on Lake Avenue, not far from where political kingmaker Marcus Hanna, also a Franklin Boulevard resident, would build his Lake Avenue mansion just a few years later.

In October 1888, Thomas Axworthy's political star crashed and burned when the Cleveland Leader broke the news that he had fled the city after embezzling some $440,000 from the city treasury. (To appreciate the size of his embezzlement, that sum would be almost $13 million in 2022 dollars.) The papers, not only in Cleveland, but across the country, were abuzz for months with stories of Axworthy's whereabouts, the efforts made by Cleveland to recover the funds he had stolen, and the inevitable litigation that followed. The person who headed the effort to locate Axworthy was attorney Andrew Squire, who just two years later would co-found Squire, Sanders and Dempsey, for many years one of Cleveland's largest and most prestigious law firms. Squire also happened to be a former neighbor of Axworthy, having lived just three houses down the street from Axworthy during the years that the latter resided on Franklin. Squire doggedly searched for Axworthy, located him in London, and traveled all the way there to confront the disgraced treasurer who was living in England's capital under an assumed name. Squire successfully negotiated a settlement with Axworthy which required him to surrender all of the cash and bonds still in his possession, and agree to sell properties that he still owned back in the States--which included Colorado and Tennessee as well as Ohio--to cover much of the rest of what he had stolen. In the end, after bondsmen made up the difference, the City of Cleveland was fully reimbursed for its loss.

After the Axworthy family moved from the house at 4206 Franklin, it was next owned and occupied by the family of a district passenger agent for the Erie Railroad and after that by a treasurer of a trucking company. In 1919, the house was purchased by a Hungarian immigrant whose family lived in it for four years before selling it to Clement and Katherine Folkman in 1923. Clement, a German immigrant who worked in Cleveland as an auto body builder, and his wife Katherine, a Hungarian immigrant, were among a large number of German and Hungarian immigrants who settled on and around Franklin Boulevard in the second and third decades of the twentieth century. A number of them, like the Folkmans, purchased grand houses on Franklin that had once been occupied by the West Side's wealthiest families, and then converted them into multi-family dwellings or rooming houses. The Folkmans created three suites in the house at 4206 Franklin, living in one themselves and renting out the other two.

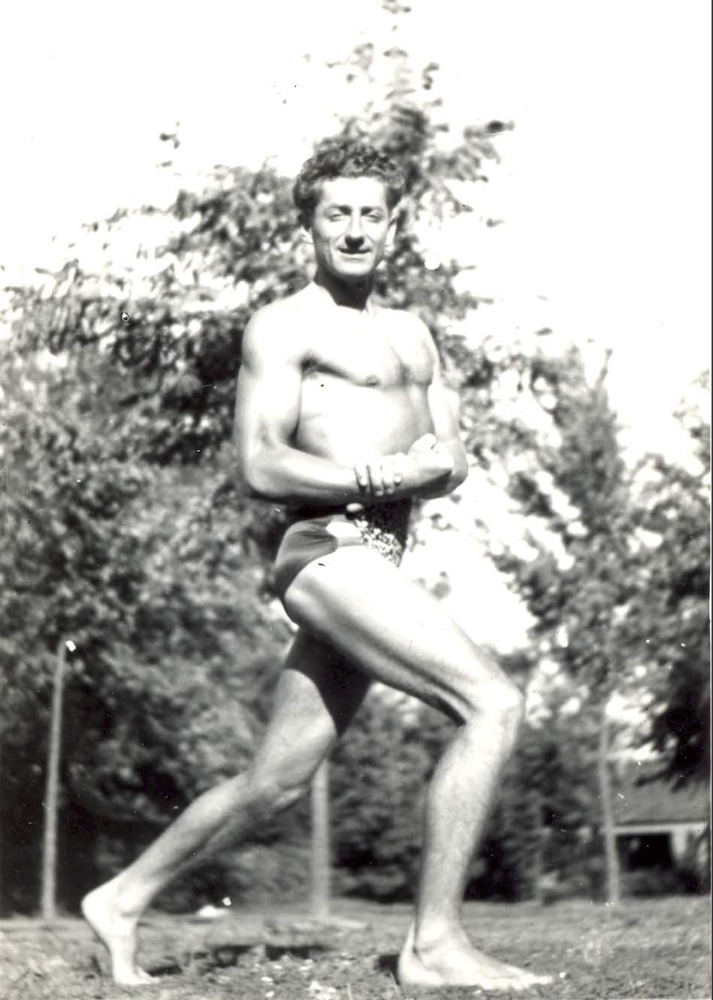

Clement and Katherine Folkman's son Clement, Jr., who was sixteen years old when his parents bought the house at 4206 Franklin, initially entered the workplace as an auto body builder like his father. In 1936, however, when he was 29 years old, he decided to become a different type of body builder. "Clem," as he was referred to by his family, was an adherent of the "physical culture" theories of Bernarr McFadden, an American entrepreneur who, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, advocated physical fitness through weight lifting regimens. McFadden later published a series of popular magazines which may have caught young Clem's eyes. With his father's help, Clem built a gymnasium in the two-story carriage house that stood in the rear yard of their property. An avid weightlifter himself, Clem soon was training young men in the neighborhood at his Folkman's Athletic Club, which he later renamed Folkman's Physical Culture Studio. By October 17, 1938, when an article about his gym appeared in the Plain Dealer, he was training 50 young men, ages 20 to 30, who came to the gym three times a week, some with Olympic medal aspirations.

For decades, Folkman's Physical Culture Studio was a popular gym and rare commercial enterprise on historically residential Franklin Boulevard. The Folkman family at some point in time built another two-story building on the property, the first story of which served as a garage, and connected the new building to the old carriage house, which itself was extensively remodeled to accommodate Clem's growing business. The gym was located on the second floor of the remodeled carriage house, and a locker room, sauna, and massage room on the first. A large round clock was also installed on a pole in the front yard that for years reminded passers by on Franklin that it was "Time To Exercise." The gym was still thriving in 1967 when legendary Plain Dealer reporter Bill Hickey paid a visit to Folkman's gym. By this time, Clem's son Ronald, a Cleveland firefighter, was also working part-time at the gym as a masseuse. Bill Hickey referred to the two of them in an article that appeared in the Plain Dealer on March 30, 1967, as "the Squires of Franklin Boulevard." When Hickey reminded Clem that he had been exercising at the gym for years, Clem, according to the article, took one look at Hickey's body and responded, "Please don't tell anybody that. It will ruin me."

In 1986, the Folkman Physical Culture Studio had been operating at 4206 Franklin Boulevard for 50 years. Cleveland Plain Dealer reporter James Neff visited the property in August of that notable anniversary year to interview Clem Folkman. When he arrived, he found an elderly man who was gravely ill and reliving past glories, and a gymnasium that was literally falling apart and papered with city building code violation notices. Clem Folkman died just three months after this interview. After the death of Clem Folkman, one of his grandsons attempted to revive the business, but was unsuccessful. In 1991, the house at 4206 Franklin Boulevard was sold to a new owner, and one year after that the buildings on the rear of the property, which had housed Folkman's Physical Culture Studio for more than a half century, were unceremoniously torn down.

Today, no evidence remains of the Folkman Physical Culture Studio where Clem Folkman trained so many Clevelanders for so many years in the theories, methodologies and regimens of Bernarr McFadden. The Thomas Axworthy House, however, now nicely renovated as a three-family dwelling, and celebrating its 156th birthday in 2022, still stands at 4206 Franklin Boulevard.

Images