Following five years of land acquisitions, demolition and construction, the Sutton Place townhouse development opened for sale to the public in May of 1971. The experimental, aluminum-based housing project was designed to draw middle- and upper-class professionals into the Moreland neighborhood. The new housing emerged from a controversial urban renewal project headed by the City of Shaker Heights during the late 1960s, and was greeted with picket signs by the Cleveland Association of Real Estate Brokers. Learn why...

Standing before a crowd of 200 community members in the fall of 1968, City of Shaker Heights Mayor Paul K. Jones offered his assurances to constituents gathered at Shaker Heights High School Auditorium. An urban renewal plan had sparked public debate over the future of Shaker Heights’ Moreland neighborhood, and the role that the City would play in shaping its landscape. Mayor Jones urged those in attendance to support the passage of bond issues totaling $7.25 million in an upcoming November election to help the “maturing city regain its youth.” The proposed development, however, went beyond cosmetic adjustments for an aging infrastructure. Both homes and commercial structures would need to be razed for the construction of a new service center and townhouse project. Over 200 families would be displaced.

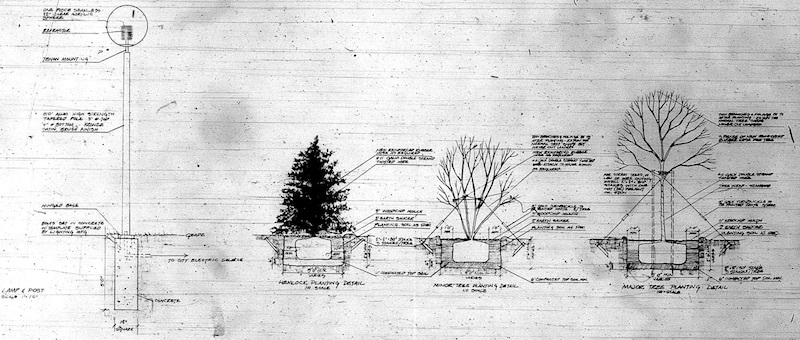

The urban renewal efforts were dependent on the public’s approval of three bond issues by a 55 percent majority vote. A $4 million bond would finance the construction of a service center on Chagrin Boulevard between Ludgate and Menlo Roads. The installation of 41 traffic signs, the relocation of city utilities for townhouses, and the widening and improvement of over a dozen streets was attached to the passage of a $3 million bond. A $250,000 park improvement bond funded the creation of a semi-public green space for the townhouse site, as well as providing for the creation of additional public spaces in Shaker Heights’ southwestern region. The proposed park and townhouse project, which would later be named Sutton Place, encapsulated the goals of this urban renewal effort: to physically recreate the Moreland neighborhood as a way of stabilizing property values and promoting the “re-integration” of white residents.

The projects, and their supporting bond issues, grew from an ambitious and highly controversial redevelopment plan created by Leonard Styche and Don Hisaka for the City of Shaker Heights. Their focus on the Moreland neighborhood was prompted by efforts to stabilize the community. During the 1960s, homes in Moreland had been placed on the resale market at an alarming rate and the community transitioned from nearly all white to over two-thirds African American. Concurrent efforts to shape and support these urban renewal plans were spearheaded by the Shaker Communities Housing Office.

Funded by both the City’s government and school system, the organization was established in 1967. Four housing coordinators were hired from the membership of the Moreland, Ludlow, Lomond and Sussex community organizations in order to aid realtors with selling properties in their respective neighborhoods. The Housing Office worked in collaboration with and generally towards the same ends as the community organizations. The group expressed concerns that if the Moreland community became exclusively African American, then other neighborhoods would follow “one by one.” While the community associations were a positive force in advocating for integration and promoting diversity as a value of Shaker Heights’ collective identity, their work during the late 1960s often focused on attracting white homeowners to the Moreland neighborhood. Support of the park-townhouse project was one such effort.

The gathering at Shaker Heights High school was not the first public meeting over the proposed redevelopment efforts. Since the Styche-Hisaka Plan was announced in February of 1967, objections, suggestions and revisions had been discussed at length by local community associations, block clubs, the Housing Office, concerned citizens and government representatives. Plans for a Civic Center in the Moreland neighborhood had been scrapped, and new emphasis was placed on diverting traffic flow away from residential neighborhoods and creating green spaces at the request of the public. The Mayor also promised that the City would assist with the relocation of those impacted by the urban renewal efforts.

A revised master plan was now on the table for a public vote. A representative of William Gould & Associates, the architectural firm employed to design Sutton Place, manned a slide projector to accompany Mayor Jones’ pitch to the concerned citizenry. Maps and photos offered those in attendance a glimpse at a possible future for the Moreland neighborhood’s townhouse and park space. The housing stock and grid layout, both of which developed outside of the control of the Van Sweringen Company during the 1920s, would be revamped with curvilinear streets and low-density housing.

The proposed Sutton Place development not only aimed to aesthetically unify the area with surrounding Shaker Heights neighborhoods, but to act as a physical barrier between the City of Cleveland and the inner suburb. The neighborhood grid was reshaped with a cul-de-sac that encircled the townhouse and park, and blocked incoming northern traffic from Kinsman Road in the City of Cleveland. In addition to new traffic patterns, 85 homes on six acres would be replaced with 15 townhouses that half-encircled open park grounds. While not yet approved by voters, the City began its efforts to acquire properties within the area beginning in January, 1966.

With support from the City’s community organizations, Shaker Heights voters overwhelmingly approved all three bond issues on November 5, 1968. The demolition of properties on Sutton (East 150th Street) and Colwyn (East 152nd Street) Roads began in January, 1969. Only one house remained at the western edge of the proposed development by November. Through its efforts to provide assistance with relocation, the City tracked 85 of the 140 families displaced by the townhouse project. Forty families relocated within Shaker, and 16 moved to Cleveland. Twenty-six single family homes and 59 duplexes were removed from the grounds. In their place, a townhouse complex emerged.

Sutton Place grew from a proposal in the Styche-Hisaka Plan to provide alternative housing options that retained “the characteristics of a fine residential community” for potential middle- and upper-class homeowners. A planned townhouse development offered “the amenities and advantages of home ownership and the conveniences of apartment living.” Designed by William Gould & Associates for Alcoa Constructions Systems, Inc., the project was an experiment in using aluminum for residential construction. Structural components, as well as windows and exterior siding, were forged of aluminum to create durable, energy efficient and weatherproof residential housing.

The City of Shaker Heights Planning Commission approved plans for the Sutton Place Townhouse Development on July 20, 1970. Construction began soon after. While the City acquired the grounds, the townhouses were built and sold under Alcoa Construction Systems, Inc. Plans for the two-story townhouses centered on the park space. Living and dining areas opened up to patios at the rear of the entrance, which faced outwards towards the semi-public grounds. Thirty townhouses comprised the park-townhouse development at completion, and prices ranged between $35,500 to $37,000 (corresponds to $235,000 in 2018). The townhouses opened for display to the public in May, 1971.

The construction of mid-priced, modern townhouses in Shaker Heights was an effort to promote integration in the Moreland neighborhood. Prior studies by the Moreland Community Association noted that white families were willing to rent in the neighborhood, but not buy homes. This was attributed to the unmodern look and interior layout of the aging housing stock. Joseph Laronge, Inc., the real estate company handling sales of Sutton Place for Alcoa, noted, “we plan Sutton Place to be a special way of living, we hope to have true integration here in a way that will make this a model community.” The new housing, however, predominately attracted upper-income, professional African Americans. The park and townhouse project still succeeded in its goals. The landscape had been reshaped and clearly delineated as a Shaker Heights community. The upper Moreland neighborhood was visually and physically set apart from the City of Cleveland at its western and southern boundaries. The neighborhood’s population density fell, and urban housing stock was replaced with green space and contemporary residences. Despite the successes of the Sutton Place project, public debate over the redevelopment and re-integration of the Moreland neighborhood continued.

Upon opening its model home to potential buyers in 1971, the Sutton Place townhouses also attracted picket signs of the Cleveland Association of Real Estate Brokers (CAREB). The African American association demanded the right to have a real estate agent on premises at Sutton Place, and to present qualified candidates for sales. Alcoa had previously extended exclusive selling rights to the white-owned Joseph Laronge, Inc. While CAREB was eventually invited to be on site during sales, and an uncharacteristic 50-50 split of commission was proposed by Joseph Laronge, Inc., the offers were refused. CAREB rejected on the grounds that African American real estate agents would not be able to go into a white community and sell new housing under similar conditions. They demanded full commission. While this request was denied by Laronge, the protest by CAREB reflected a larger, ongoing public debate over both the City’s urban renewal plans and reintegration efforts in the Moreland neighborhood. The role of the City and the community associations in both refashioning the physical landscape and promoting the reintegration of white residents in African American communities increasingly came under fire from the public during the 1970s and 1980s. These debates eventually advanced a more nuanced, balanced and self-reflective approach to advocating for integration in white and African American neighborhoods by the City of Shaker Heights and its neighborhood community associations. The City of Shaker Heights has continued to promote integration and pursue redevelopment projects that diversity housing stock within its southern neighborhoods. A new townhouse development, The Van Aken Townhouses, opened for sale in 2018 and is planned to include 33 new-construction townhomes near the intersection of Sutton Road and Van Aken Boulevard.

Images