The William F. Cody Lawsuit

Buffalo Bill's Failed Attempt to Recover His Grandfather's Euclid Avenue Property

He hunted buffalo on horseback. He was a top scout for the United States Army. He created and starred in his own magnificent Wild West Show which played to huge crowds all across America and before the crowned heads of Europe. However, in 1882, William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody was simply no match for Cleveland's justice system.

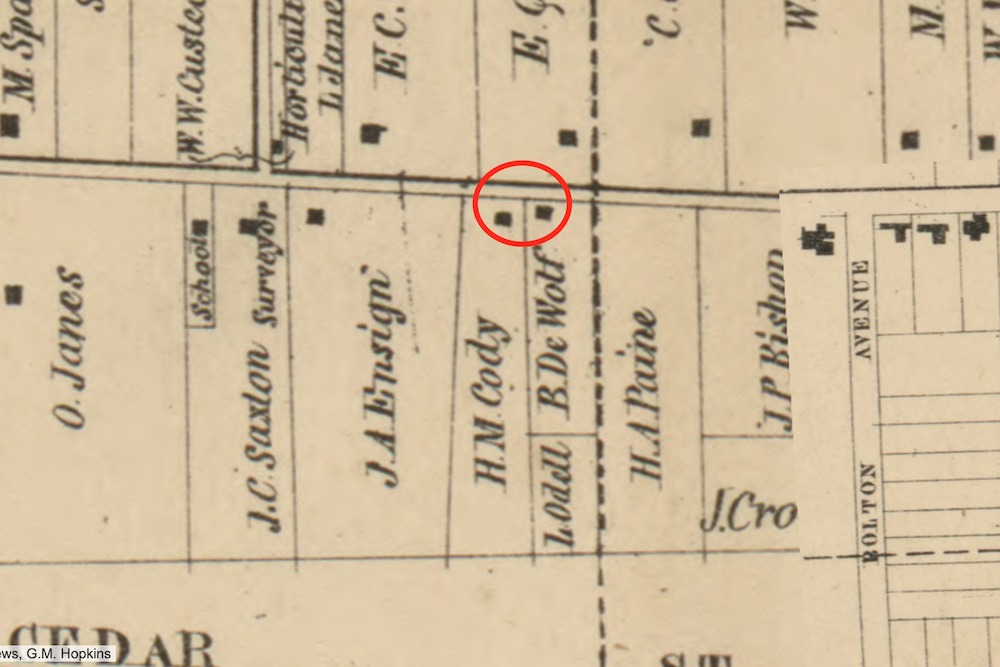

Philip Cody, the grandfather of Buffalo Bill Cody, was one of Cleveland's pioneer settlers. A Massachusetts native, he lived much of his life in Toronto, Canada, where he became wealthy operating a tavern and speculating in real estate. In about 1830, when he was 60 years old, Cody, his wife Lydia, and nine of their 11 children, moved to Cleveland, then a small village on the south shore of Lake Erie. According to Cody family tradition, they moved here because of political unrest in Canada and because of business opportunities in Cleveland, which was beginning to boom as the result of the construction from 1825 to 1832 of the Ohio and Erie Canal . Cody settled on a 55-acre farm in what was then Cleveland Township. (It became East Cleveland Township in 1845, and in 1872 was annexed to the City of Cleveland.) The farm had 342 feet of frontage on the south side of Euclid Avenue just west of what is today East 86th Street, and stretched all the way south to Quincy Avenue in what is today Cleveland's Fairfax neighborhood. Philip Cody lived on this farm for almost twenty years, continuing to engage, as he had in Canada, in real estate transactions, many of them with members of his family who lived nearby. In or about 1847, the year Lydia died, he moved in with his daughter Sophia, whose husband Levi Billings operated a tavern near Doan's Corners, just a half mile or so east of the Cody farm. A few years later, on January 2, 1850, at the age of 80, Philip Cody died.

And that might have been the end of this story except for two developments which occurred in the Cody family almost three decades after Philip's death. First, according to newspaper accounts, in October 1878, Joseph A. Cody, a son of Philip Cody who had lived with or nearby his father during the 1840s, confessed on his deathbed to his nephew Lindus Cody that he had forged deeds and swindled his siblings and their descendants out of their share of Philip's farm. And second, the story about Joseph Cody's deathbed confession eventually reached the ears of Lindus' cousin, William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody, who by this time had become one of the most famous celebrities in late nineteenth century America.

"Buffalo Bill" Cody was born near LeClaire, Iowa in 1846. His father, Isaac, was one of Philip Cody's 11 children. Isaac had come to Cleveland with the rest of the family, but had left the area around 1840, following his brothers Elijah and Philip Jr. west to Iowa, before eventually moving to Kansas in 1854. Shortly after his arrival there, Isaac was stabbed twice in the chest while giving a speech opposing the extension of slavery in the state, suffering injuries from which he never fully recovered. When he died in 1857, his 11-year old son Bill had to go to work, according to biographers, in order to help his mother and four sisters. He became a wagon train messenger, a pony express rider, a buffalo hunter, and finally a scout for the U.S. Army. By 1870, his western exploits caught the attention of Edward Judson, who, under the pseudonym "Ned Buntline," began writing a series of dime novels about "Buffalo Bill" Cody which soon made him a household name in America. Capitalizing on his newfound fame, Cody, when he was not scouting for the Army, began starring in plays (called "combinations"). His performances in these plays, which were based upon his reputed feats in the Wild West, further enhanced his fame, especially back East. Then, in 1883, Cody, with the assistance of his publicist John Burke and others, created Buffalo Bill's Wild West, a show, which, unlike the plays in which he appeared, featured real cowboys engaged in rodeo events, reenactments of buffalo hunts, feats of marksmanship (starring, among others, Ohio's Annie Oakley), and amazing tricks performed on horseback (some by Adele von Ohl Parker, who later created her own Wild West Show on Parker Ranch in Norh Olmsted, Ohio), all performed in outdoor venues. The performances of these shows over the next three decades would cement Cody's fame for several generations of Americans, and was a major influence on the development of twentieth century western films, rodeos and circuses in this country.

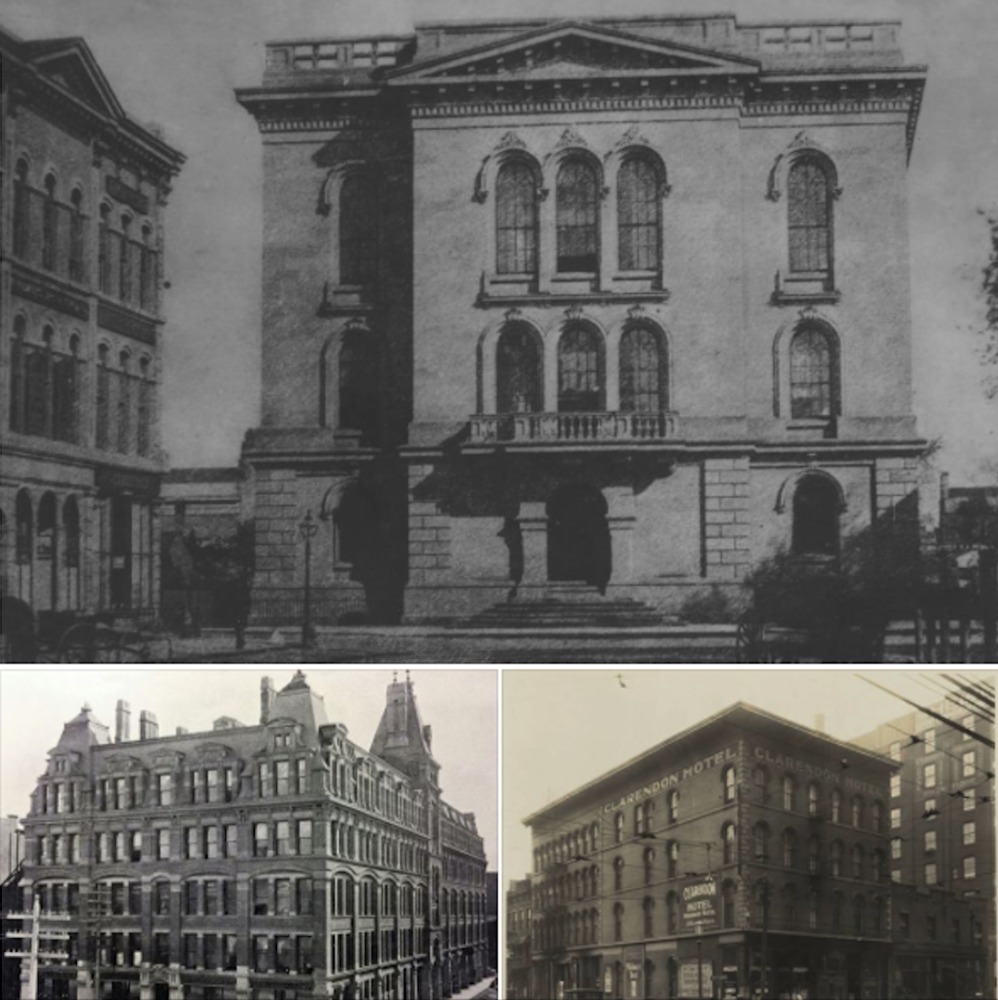

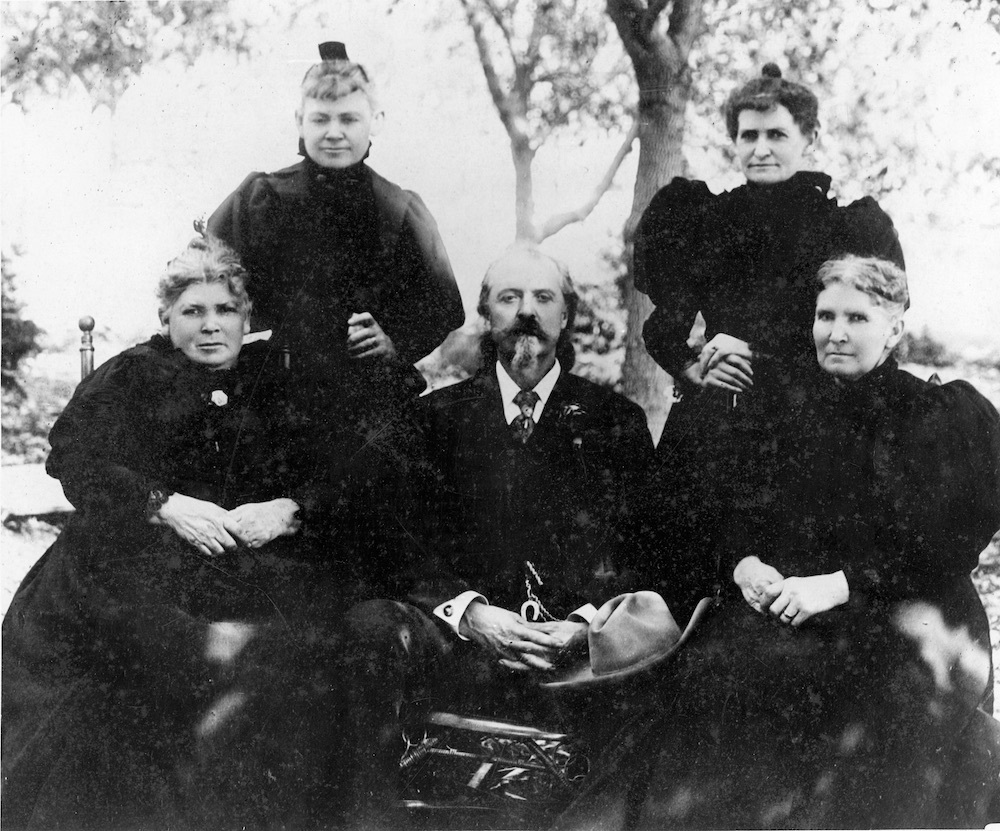

In 1880, just three years before Buffalo Bill Cody launched his Wild West Show, his Aunt Margaret, the widow of his father's brother Elijah, learned about the alleged fraudulent acts of Joseph Cody and, according to news accounts, launched her own two-year long personal investigation into the matter, traveling around the country, examining deeds, identifying heirs, and talking to family members and others with knowledge of Joseph Cody and the mental condition and business acumen of Philip Cody in the 1840s. In early 1882, she contacted her nephew Buffalo Bill about the matter, not just because he was a celebrity, but also likely because she needed money to file a lawsuit. According to one source, Buffalo Bill, who agreed to bankroll the effort--in large part, he later claimed, in order to help his four sisters--paid $5,000 to retain Hutchins, Campbell, and Johnson, a prominent law firm in Cleveland with offices in the Blackstone Building, located just a block or so from the old County Court House on the northwest quadrant of Public Square. It was there that the Cody lawsuit would be heard before Judge Gershom Barber, a reputedly able jurist who had served as a brigadier general during the Civil War. It wasn't long before Cleveland's major newspapers--the Plain Dealer, the Leader, and the Herald, as well as major newspapers across the country, were abuzz with articles claiming that a lawsuit was about to be filed here in Cleveland against a number of wealthy Euclid Avenue residents and that the famous Buffalo Bill Cody was a plaintiff in the suit. Estimates of the value of the land which Cody was trying to recover for his sisters and the other heirs ranged, according to different articles, from $300,000 to $3,000,000.

The Cody lawsuit was filed in Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court on July 22, 1882. Named as plaintiffs were 14 heirs of Philip Cody representing six of his 11 children, led by William F. Cody. (Of Philip Cody's remaining five children, one had died without children, two were alleged to have participated in the fraud against the heirs, and the heirs of the remaining two, Elizabeth Custead and Lydia O'Dell, apparently--as intimated in a letter to the editor which appeared in the Cleveland Leader on March 17, 1882--declined to participate in the lawsuit). Named as defendants were 104 Clevelanders who were alleged to be at the time of the filing of the suit the owners of the land that had constituted Philip Cody's 55-acre farm at the time of his death in 1850. The defendants included four upper class Cleveland families who lived or owned land on Euclid Avenue, by then one of the most famous residential streets in America, if not the world. The vast majority of the remaining defendants were middle class or working class Clevelanders, most owning or living in houses on Lincoln Avenue (today, East 83rd Street), between Cedar and Quincy Avenues. The southernmost part of this section of the street was fast becoming an ethnic enclave for Cleveland's Czech immigrants who would just one year later organize St. Adalbert Catholic Church on Lincoln Avenue, between Garden (today, Central) and Quincy Avenues.

The plaintiffs' theory of liability in the Cody Lawsuit was that the 104 defendants had purchased their land, either directly or indirectly, from, in essence, thieves--the petition claiming that Philip Cody, Jr., as well as his brother Joseph, had fraudulently acquired their father's farm in the 1840s--and that the law does not recognize the validity of even a bona fide purchaser's title when it is obtained from a thief. The petition further claimed that the fraud was committed by Joseph Cody and Philip Cody, Jr., when they took advantage of their father's diminished mental condition and either forged deeds in his name or induced him to sign deeds, conveying half of Philip Sr.'s farm, in trust, to Joseph Cody's wife, and the other half to Philip Cody Jr.'s wife. For their remedy, the plaintiffs asked the court to convey to them a six-tenths interest (because only six of the ten Cody children or their descendants were participating in the suit) in each defendants' property, subject to adjustments for improvements made and for rents collected.

The Cody lawsuit plaintiffs never were allowed an opportunity to proceed to trial and present evidence in support of their petition's allegations in open court. Instead, their petition was subjected to a number of formulaic nineteenth century procedural motions by attorneys representing various individual defendants and groups of defendants, including several filed by Ephraim J. Estep, a well known member of the Cleveland bar and former resident of Euclid Avenue (see Allen-Sullivan House story), who represented 62 of the defendants, including Darius Cadwell, one of Judge Gershom Barber's colleagues on the Common Pleas Court bench. Essentially, the defendants complained that plaintiffs' petition did not allege sufficient specific facts from which the court could legally find for the plaintiffs. Judge Barber, who appears to have agreed with the substance of the defendants' motions, gave the plaintiffs two opportunities to correct the alleged legal deficiencies in their petition and, when they failed to do so to his satisfaction, dismissed their petition in May of 1883. It is difficult today--even for a retired lawyer--to determine the exact grounds upon which the court based its decision. However, the plaintiffs' attorney, John Hutchins, in an interview he gave which appeared in the Plain Dealer on July 23, 1889, stated that the judge's decision was based on a statute of limitations argument. This essentially means that the time within which the plaintiffs were legally required to bring such an action based on fraud had expired before the suit was filed. The Cody heirs filed an appeal from Judge Barber's judgment to the Cuyahoga County Court of Appeals (then called the District Court), which affirmed the lower court's judgment in October 1885. An appeal to the Ohio Supreme Court was dismissed in November 1887 "for failure to file printed record," an indication that Buffalo Bill Cody had, by this time, tired of the case and was no longer willing to throw good money after bad.

In addition to the Plaintiffs not getting their day in court, it should be noted that neither did Joseph Cody and Philip Cody, Jr., both of whom had died before the lawsuit was filed. While the dismissal of the case was a victory for the defendants, it left unanswered the question of whether Joseph and Philip Cody, Jr. did, in fact, commit fraud and deprive the other children and their heirs out of a share of the Cody farm. On that question, it must be emphasized, as noted above, that Philip Cody engaged in a number of real estate transactions in the 1840s wth members of his family, including his sons-in-law William Custead, John Odell, and Levi Billings. And yet none of these individuals, or the Cody daughters that they married, were ever charged with fraud.

Over 130 years have passed since William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody came to Cleveland in a failed effort to recover his grandfather's 55-acre farm on Euclid Avenue. Unlike other Cleveland Historical stories that are about people or places, little is left standing in Cleveland to commemorate or otherwise remind us of Buffalo Bill's 1882 lawsuit. But there are some places which can serve to do so. You can make a trip to East Cleveland Township Cemetery and there view the weathered gravestone of Buffalo Bill's grandparents, Philip and Lydia Cody. Or you can take a drive down East 83rd Street, just south of Cedar Avenue, and see three houses at 2202, 2208 and 2210 East 83rd that were standing in 1882 and were owned and/or occupied by defendants in the Cody Lawsuit. And finally, you can visit the website of the International Cody Family Association, formed shortly after the death of William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody in 1917, to travel back to a time when Buffalo Bill Cody was a household name in America, when Euclid Avenue was one of the grandest residential avenues in the United States, and when a trip by Buffalo Bill to Cleveland for the purpose of bringing a lawsuit against wealthy Euclid Avenue residents was an event which captured the attention and interest not only of Clevelanders, but of people all across the country.

Images