If Anna M. Edwards, the first Director (then called "Superintendent") of the Eleanor B. Rainey Memorial Institute could attend an El Sistema concert today, she would probably at first be surprised that the Institute was involved in such a thing. But once she came to understand what music, and other visual and performing arts, programs at Rainey were doing for the children of Cleveland's Hough neighborhood, she would, while perhaps personally noting the irony of it all, be very pleased.

Anna M. Edwards dreamed of a career in music. Born in the Dayton, Ohio, area in 1849, she was the daughter of a Presbyterian minister who had moved his family to Cleveland near the end of the Civil War. Here, she attended local schools and then studied music at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music. By 1870, she was teaching music at the Lake Erie Seminary (today, Lake Erie College). However, when she was just 25 years old, her music career came to an end as a result of her involvement in the Women's Crusade (1873-1874), a national protest movement by women against America's saloon keepers. Edwards, according to her friend Edith Stivers, was persuaded by Frances Willard, legendary temperance reformer and women's suffragist, to give up her music career and go to work for the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), a national organization led entirely by women that grew out of the Crusade and which was formally organized here in Cleveland in 1874.

Edwards became the WCTU's Superintendent of Scientific Temperance Instruction for Ohio. This position required her to travel around the state, and later around the country, giving temperance lectures wherever she went. After a decade or so of this exhausting work, she began spending more of her time working at the non-partisan WCTU mission on St. Clair Street (St. Clair Avenue) near Willson Avenue (East 55th Street). The mission was located in a neighborhood that was brimming with saloons and home to many Eastern European immigrants, especially Slovenians. One day, according to accounts by several of her contemporaries, Edwards saw several young boys making a delivery of beer to a local saloon. They were drinking the "dregs" of the beer they were delivering and appeared to be intoxicated. Witnessing this was an epiphany for her. She decided then and there to devote the rest of her life to keeping boys like these away from saloons.

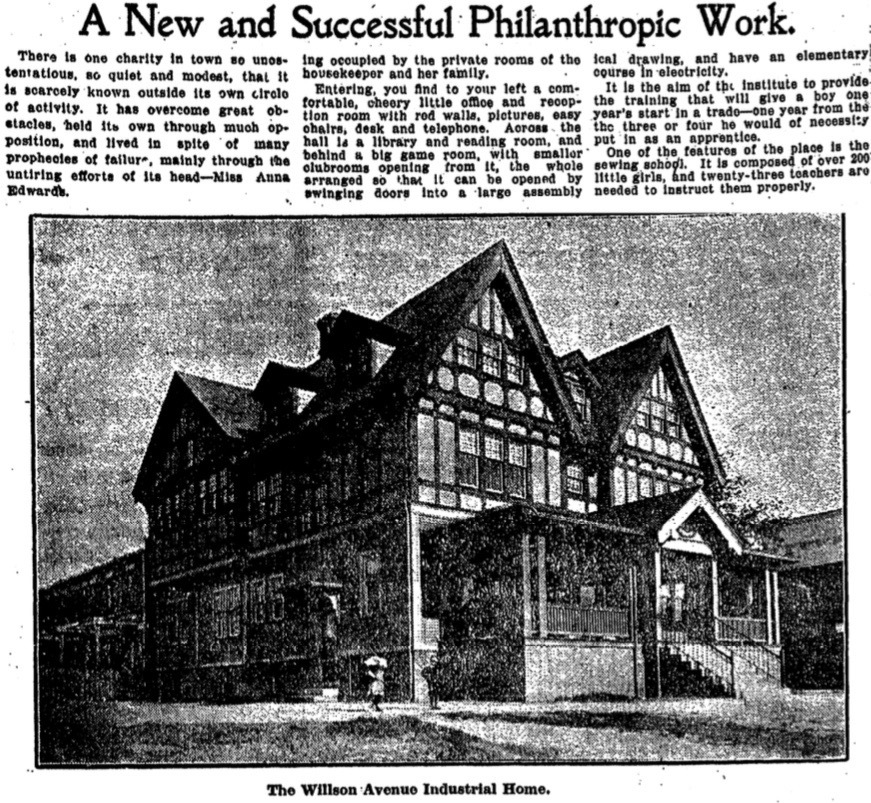

In 1888, Edwards took over the chairmanship of a WCTU reading room located on Willson Avenue, re-energized the neighborhood "Band of Hope" (a temperance pledge youth group), and opened the Flag Coffee House (so-called because of the flags she placed in its windows). The coffee house openly and actively competed with nearby saloons by offering boys a full dinner and a cup of coffee for just ten cents. Her work with the boys of this neighborhood eventually caught the attention of Eleanor B. Rainey, the widow of a wealthy Cleveland industrialist, who offered to provide Edwards with a larger and better facility for her work. Rainey purchased a lot on the northeast corner of Willson and Dibble Avenues and built on it a three-story, 9,000-square-foot building, designed in the Tudor style by architects Badgley and Nicklas to resemble a large house. Officially called the Willson Avenue Industrial Institute, it opened in 1904. It had offices, and reading and game rooms, on the first floor; classrooms and a gymnasium on the second floor; and a custodian's apartment on the third floor. (Walfred and Anna Danielson, immigrants from Sweden and Canada respectively, and their son Harold, lived in that apartment and worked for the Institute for much of the period 1904-1940.)

Just one year after the Institute opened, it was faced with a crisis that threatened its continued existence. Eleanor Rainey, its benefactor, suddenly died. The crisis was resolved when her heirs stepped in and agreed to continue their mother's support of the Institute's work, and the non-partisan WCTU (later known as the Women's Philanthropic Union) agreed to rename the Institute the "Eleanor B. Rainey Memorial Institute." For the next half-century, the operations of Rainey as a settlement house were funded by Eleanor Rainey's heirs, particularly by her daughter Grace Rainey Rogers, who became sole owner of the building on East 55th Street and Dibble Avenues in 1931 and the sole surviving child of Eleanor Rainey in 1938. During this period, Rainey Institute functioned as a traditional settlement house, offering instruction in industrial trades for boys, home economics instruction (and also stenography and bookkeeping) for girls, and youth recreational activities. One of the young Slovenian boys who benefitted from these programs was Frank Lausche. He grew up to become Cleveland mayor (1942-1944), Ohio governor (1949-1957), and one of Ohio's United States Senators (1957-1969).

Anna Edwards served as superintendent of Rainey Institute until her death in 1923. She was succeeded by her younger sister, Flora, who served until her death in 1949. Upon her death, Flora Edwards was succeeded by Jessie Peloubet, whose mother was a close friend and associate of the Edwards sisters. Already 67 years old when she became superintendent, Peloubet faced many challenges during the decade of the 1950s. In 1957, the Goodrich settlement house moved from E. 31st Street to a location on E. 55th Street just up the street from Rainey Institute. The new Goodrich-Gannett neighborhood center, and several local organizations that provided funding to Cleveland settlement houses, put pressure on Rainey to either close, merge with Goodrich-Gannett, or move elsewhere.

Additionally, the decade of the 1950s saw the Hough neighborhood in which Rainey was located undergo racial transition, changing from primarily white and middle or working class in 1950 to primarily African American and working or lower class by 1960. Finally, the estate of Grace Rainey Rogers, Rainey's benefactor, who died in 1943, remained in administration well into the 1950s, forcing Peloubet to deal with estate executors and trustees in New York for the Institute's operational expenses. In 1955, pursuant to the terms of Rogers' will, the Rainey Institute land and building were finally conveyed from the estate to a newly formed non-profit corporation and a board of trustees was appointed that was charged with the financial management of an endowment left by Rogers for the continuing operating expenses of Rainey.

The record is silent as to how well Peloubet addressed these challenges, but by the end of 1959 she was no longer Rainey's superintendent, and, for a six-month period, Rainey was administered by League Park Center, Inc., a social services agency that was located, like Rainey, in the Hough neighborhood. According to an article which appeared later in the Cleveland Press on May 19, 1964, Rainey almost closed during this period. Shirley Lautenschlager, a social worker with a degree from Western Reserve University's School of Applied Social Sciences, was hired by the board of trustees in June 1960 to become the new director, of Rainey--the title of "superintendent" apparently having been discarded. Lautenschlager, who noted that, when she arrived, Rainey was functioning as little more than a recreation center, instituted a number of new social programs at Rainey that were intended to serve Hough's current population, including after school care for seven to twelve year olds; activities for teenagers including game rooms, clubs, and dances; and gardening, cake decorating and sewing classes. Several years later, in 1964, following the taking of a survey in the Hough neighborhood, Rainey also began offering piano lessons to the children of Hough. These and other music classes proved so popular with the neighborhood's parents and children that two years later Rainey Institute decided to concentrate its efforts solely in the field of music, becoming an affiliate of Cleveland Music Settlement in 1966. The institute also appointed a new Director that year who had a background in both music and social work.

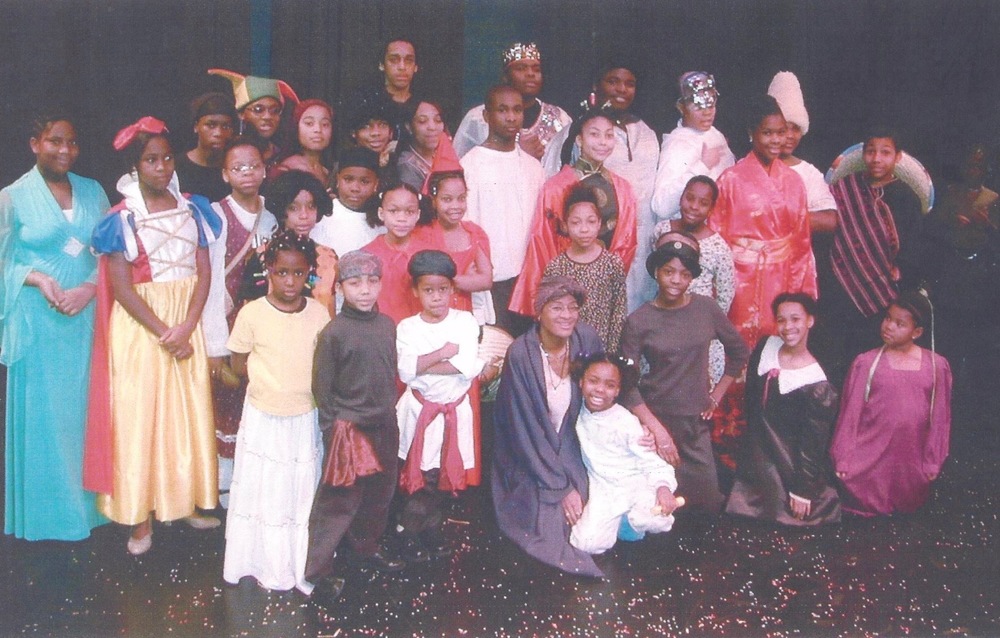

For Rainey Institute, Zandra Richardson, the new Director hired in 1966, was like the second coming of founder Anna Edwards. Like Edwards, Richardson came to Cleveland from the Dayton area, and like Edwards, Richardson's first love was music. Both Edwards and Richardson became involved in social services because of their desire to help children in need and both ultimately worked for more than four decades helping children in what is today Cleveland's Hough neighborhood. Zandra Richardson, who served as Director from 1966 until 2008, left a deep imprint on the history and evolution of Rainey Institute as an arts center for underprivileged children. During her tenure, many new music and other arts programs were introduced at Rainey. One of the earliest new programs was a summer camp program promoted by Cleveland Music Settlement and Karamu House in 1967, the first summer following the 1966 Hough Riots. At summer camp, African American children were introduced to art, drama, African drumming, vocal music and dance. Several years later, Rainey expanded the summer camp program to include drama, art and music, and dance. Kids attending also received instruction in reading, math, and creative writing, and participated in recreational activities.

As time passed, Rainey's focus as a music and arts center gradually changed as theater and dance became more popular than music instruction. As a result, in 1997 Rainey severed its affiliate status with Cleveland Music Settlement. During first half of Richardson's directorship, she and Rainey's Board of Trustees, anchored by long-time trustee Theodore Horvath who worked tirelessly to preserve Rainey Institute's endowment, also initiated a long-term plan to build a new and larger facility so that more children in Hough and other nearby neighborhoods could be introduced to the visual and performing arts. In 2011, just three years after Richardson retired as Director, and with the guidance of new Director, Lee Lazar, many Cleveland businesses and charitable organizations, and Cleveland Councilwoman Fannie Lewis, Rainey Institute opened its new 27,500-square-foot Arts Center, just down the street from the old Rainey Institute building. In the same year as the new Arts Center opened, Isabel Trautwein, a violinist with the Cleveland Orchestra, established an El Sistema string orchestra program at Rainey. El Sistema, one of the most notable programs at Rainey today, promotes peaceful social change through music.

Under the directorship of Richardson and her successors, there have been many success stories at Rainey, of students who went on to have fulfilling careers in many different fields of endeavor ranging from music to government service to teaching to the business world. One of those former Rainey students is Stephanie D. Howse, an African American woman who had a successful career as an environmental engineer, before turning to public service and becoming State Representative from Ohio's 11th District. Today, Rainey Institute is a thriving art center, each year serving more than 2,500 children like Howse who hail from the Hough and other nearby neighborhoods of the City of Cleveland. And the old Rainey Institute Building? It has not been forgotten by the City of Cleveland, which made it a Cleveland Landmark in 2018. In 2020, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places. From an early twentieth-century settlement house founded by a woman who gave up a career in music to help immigrant children threatened by saloons to a twenty-first century arts center, which uses music and other visual and performing arts to cultivate self-expression and promote social emotional growth in a new demographic of disadvantaged children in the neighborhood, Rainey Institute has come full circle, a statement with which Anna M. Edwards would certainly agree, even if she did find it ironic.

Images