Longwood (Area B) Urban Renewal Project

“Cleveland's Cabrini-Green”

Beginning in 1955, Longwood (Area B) was the first urban renewal project in accordance with the General Plan for Cleveland of 1949. The small, yet densely populated, neighborhood of about 56 acres was bordered by Scovill and Woodland Avenues to the north and south; and by East 33rd and East 40th Streets to the west and east. The project served as a model for subsequent urban renewal projects in Cleveland, though not always a positive one. Opposition and criticism to the project was visible since the beginning and would continue through the following years. Roadell Hickman stated in a Plain Dealer editorial in 1987, “Longwood became Cleveland’s Cabrini-Green, the notorious Chicago public-housing project. Both began with a vision to save a neighborhood but became a symbol of what was destroying it.” Longwood and Cabrini-Green did have some differences, however. The Cabrini-Green project in Chicago was intended to be public housing, whereas Longwood was not intended to be public housing, but rather low-cost housing.

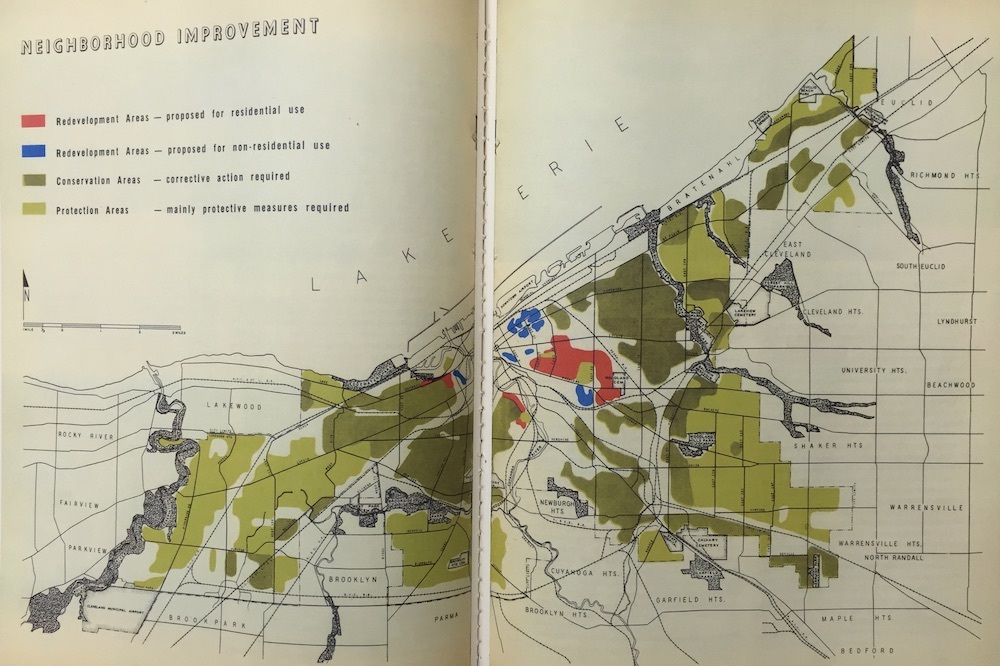

The General Plan for Cleveland was formed as a flexible blueprint for city growth up until the 1980s. Longwood (Area B), among the other urban renewal projects in Cleveland, was a response to growing blight and decay in inner city neighborhoods. The city government of Cleveland was proactive about maintaining and developing its inner city since the beginning of the 20th century. A city planning commission was established in 1915, and in 1933 Cleveland established the Metropolitan Housing Authority. Local businesses and corporations also took action and formed the Cleveland Development Foundation in 1954 with a revolving fund of $2 million to invest in urban renewal. Businesses and corporations in Cleveland believed that by creating a better inner city in close proximity to jobs, they could attract middle class workers that relocated to the suburbs.

In 1955, the Longwood neighborhood had a total of 295 dilapidated buildings that housed around 1,500 families. The project called for the total clearance of the area, with the exception of a few churches and city buildings. The area consisted of five privately owned developers and called for the construction of 836 new dwellings throughout the neighborhood, as well as shopping centers and an improved street plan. Various city agencies touted the project as an almost immediate success story through multiple newspaper articles and city publications. The land was acquired, leveled, and rebuilt relatively quickly and new residents were moving in as early as 1958. Any small success of the project was covered in the local newspapers to paint a clear picture that Longwood was right on track to become the model that the city government hoped it would be.

Despite the proclaimed success of the project by city publications, problems and critics were prevalent and visible from the beginning. Critics claimed that the project was far too expensive and was taking too much time to fully complete with the quality that was initially envisioned. The project, as well as most urban renewal projects, also disproportionally affected African Americans, which caused many residents to speak out against it. According to Renewing Inequality, of the 1,100 people displaced by the project by 1961, 99% of them were people of color. Tenants also consistently made claims of mismanagement, pest problems, and poorly built structures. According to Residents also had to be relocated for the duration of the construction of the project and some found themselves in a worse situation than they were before having to move out of Longwood. Tenants also picketed and protested their grievances several times, with the first tenant strike occurring in 1958. Tenants in a small section of Longwood (Area B) called Longwood Village organized a strike with grievances that included high rents and rent increases, racial discrimination, rats, and property mismanagement. The primary cause for the strike, being rent prices, was never resolved on account of rents being set and controlled by the Federal Housing Administration. Everyone involved, however, did agree that the rents were too high to be considered low cost housing. The rent strikes reveal a major concern with urban renewal that civic and business leaders did not foresee. Longwood was still surrounded by other slums and dilapidated neighborhoods and the new housing was not affordable. Middle-class suburbanites did not want to move into the inner city and the inner-city community could not afford the new housing. Eugene Segal, a reporter for the Plain Dealer, stated, “If one group can’t afford the new housing and the other won’t have it, whom are we building for?”

The housing developments in Longwood (Area B) changed ownership multiple times over the decades following the project. Excessive vacancies in the housing developments caused the owners to default on their mortgage payments in 1963. To stop them from foreclosing, the Cleveland Development Foundation set up a subsidiary called the Longwood Housing Association to take advantage of a new Federal Housing Administration amendment and get a loan. The loan paid off banks and money lenders first, then a portion of it was used to pay developers to help recoup their losses, and what was left was paid to the city of Cleveland which was only about half of what the Cleveland Development Foundation initially paid in advance to the builders of the project.

The grand ambitions of the Longwood (Area B) project were unfortunately never realized. Financial, management, and vacancy problems continued to plague the neighborhood into the 1990s. A new type of subsidized housing was built in the early 2000s, which replaced Longwood Apartments. The new housing development was named Arbor Park Village and was intended to include educational classes, recreational activities, and resources to help people find better jobs. Though flaws persisted in Longwood (Area B) in the decades following the project, perhaps Arbor Park Village can fulfill some the original promises that were made.

Images