Buried in the shale cliffs of Cleveland Metroparks Rocky River Reservation, the bony armor of a prehistoric monster was uncovered by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History in 1928. The discovery of these fossilized remains, along with the subsequent amassing of Devonian era specimens from the Cleveland Metroparks, helped set the stage for the museum to emerge as a prestigious scientific institution.

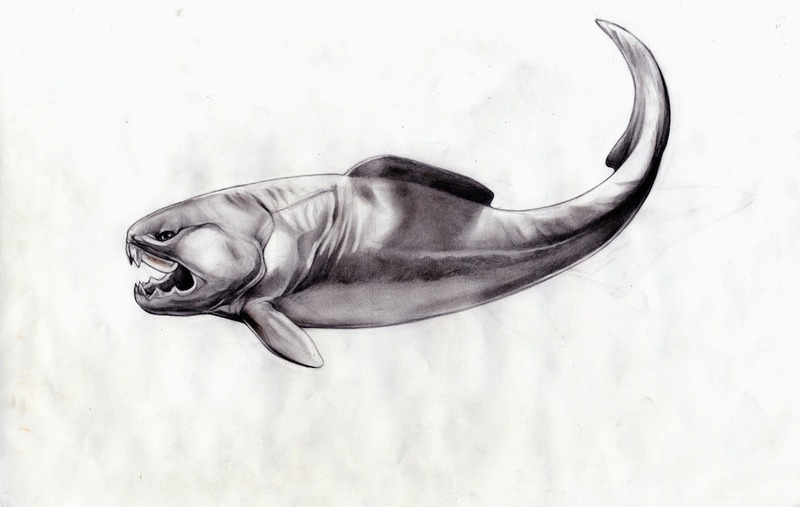

Dragged silently downward by the weight of its armored head, the Dunkleosteus terrelli’s lifeless body disappeared into a murky cloud rising from the sea floor. A death shroud of mud and freshly deposited sediment encased the remains. As the body disintegrated in the stagnant oxygen-starved environment, organic chemicals were released into the surrounding ooze and triggered the formation of a casing around the decomposing matter. Sediments continued to accumulate above the remains. Pressure and chemical reactions turned the muds into shale, and the concretion to stone. The Dunkleosteus lay entombed for over 360 million years, when the clinks of a pick against stone rejoined the fearsome predator with the living world in the summer of 1928.

This was no happenstance reunion; Peter Bungart and Jesse Earl Hyde of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History had been hunting sharks and armored fish in the Cleveland Metropolitan Park System for almost six years. Walking along the river’s edge in the Rocky River Reservation, the intrepid duo observed a curved shape in the shale nearly 20 feet above them. Bungart, a paleontologist, scaled the steep wall and wielded the tool of his trade. A bone of the Dunkleosteus was found. With permission of the Park Board, they returned ten days later to excavate the prehistoric monster. Its ancient tomb was carved from the cliff, and lowered to the bank of the Rocky River in 300 pound chunks. The solidified remains of primeval mud, ooze and petrified bone were transported to the Cleveland Museum of Natural History’s headquarters on East 9th Street and Euclid Avenue.

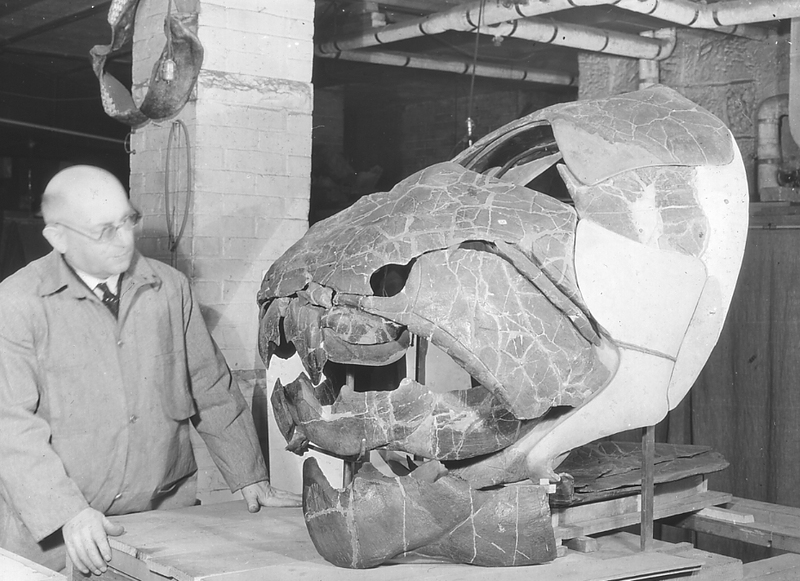

Bungart patiently chipped away at the stone in the basement of museum headquarters for nearly eight years. Armed with a dental drill, hammer, chisel, and blow torch, he released the Dunkleosteus from its encasement. With equal perseverance, the flattened remnants of the warrior fish were reshaped and the prehistoric puzzle was pieced together. Only the bony armor comprising the predatory placoderm’s skull survived, but Bungart’s reconstruction was still the largest and most complete non-composite representation of the Dunkleosteus terrelli species in the world. Following the discovery of the armored fish by Ohio geologist Jay Terrill in 1867 along the shale banks of Cove Beach in Sheffield Lake, fossilized remains of the Dunkleosteus had been displayed at prestigious institutions such as the British Museum and the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Bungart’s monster, culled from the rocks of the Rocky River Reservation, became the first distinguished fossil fish specimen of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

The frightening vision of prehistoric life not only helped accredit the Cleveland Museum of Natural History as a relevant scientific institution, but presented a means for the new museum to promote its mission of public education. Imaginations in Cleveland had long run wild over the vicious fish that thrived in the region during the Devonian Period. Similar to its massive dinosaur successors, exhibition of the attention-grabbing skull discretely passed on scientific knowledge to curious museum visitors. Without a whisper, the peculiar depiction of ancient life inspired awe while evoking questions about geology and evolution.

The petrified bones also helped validate the need for conservation and preservation of land within the Cleveland Metropolitan Park System. The taxes of Clevelanders were being funneled to the development of parks on the outskirts of the city, necessitating regular illustrations of the undertaking’s public benefits. The budget and efforts of the Park Board, however, were focused on the acquisition and development of land during these formative years. Providing civic institutions such as the Cleveland Museum of Natural History access to parklands for field work and educational programming was paramount to inscribing value into the landscape.

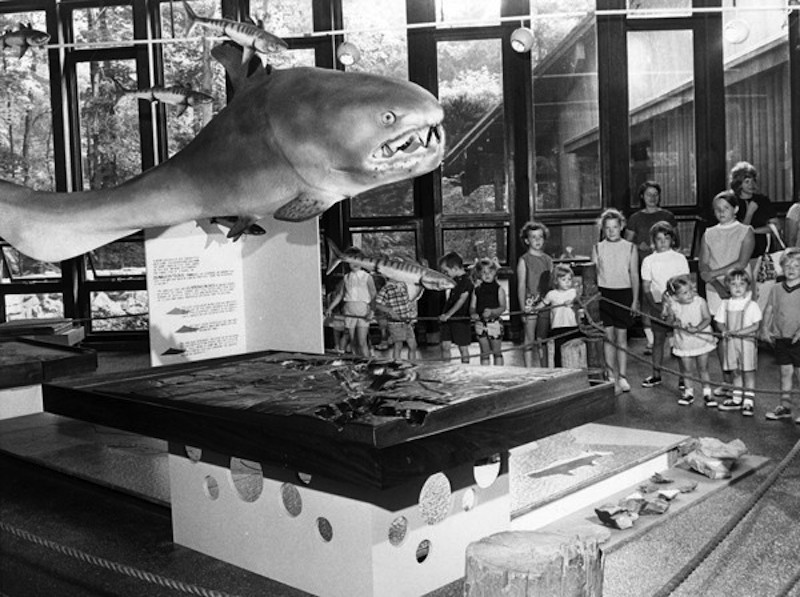

Until the 1950s, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History took the lead in developing educational programming and performing scientific research in the park system. Fossil hunting expeditions continued, and the museum soon amassed a world-renowned collection of Devonian fish fossils. Both Big Creek and Rocky River Reservations proved to be incredibly fertile grounds for unearthing long-hidden vestiges of armored fish and sharks. Even as the museum’s collection expanded in size and diversity, the vicious predator Dunkleosteus terrelli remained the most famous of the prehistoric placoderms. The Cleveland Museum of Natural History continues to maintain its notable collection of specimens, one of which is displayed in Kirtland Hall on museum grounds. The cast of a Dunkleosteus skull, accompanied by a model representation of the armored fish in its horrifying entirety, can be viewed at the Cleveland Metroparks Rocky River Nature Center.

Audio

Images

The armored fish found by Peter Bungart and Jesse Earl Hyde in the cliffs of Rocky River Reservation was known as a Dinichthys terrell at the time of its unearthing. The armored fish was renamed in the mid 20th century following the discovery that the "terrible fish" should be classified within a new family. The name Dunkleosteus terrelli was bestowned upon the genus in honor of David Dunkle, a former curator of paleontology and superisor of research at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Dunkle was an authority on the Dinichthys terrelli, and helped amass the museum's world-class collection of Devonian fish fossils.