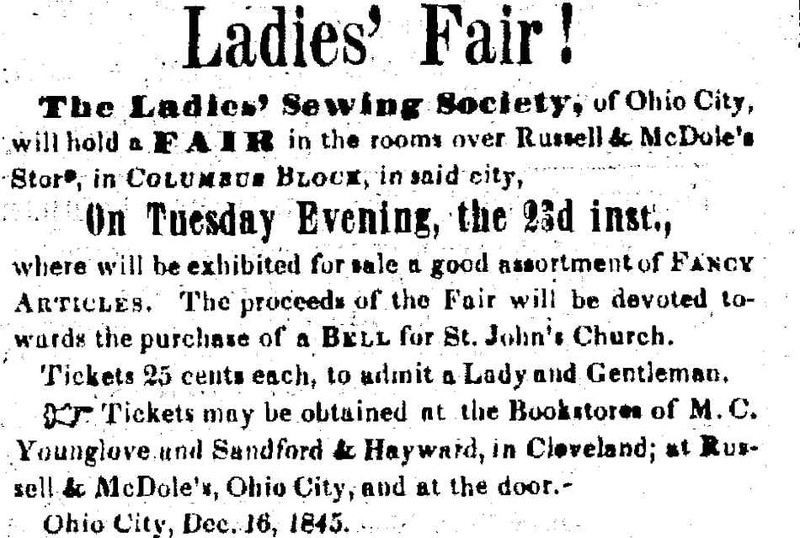

Originally founded as Trinity Church in Old Brooklyn in 1816, Trinity remained a west side congregation until 1826, when church leaders decided to relocate to the east side of the Cuyahoga River near Public Square. At that time a number of families who attended Trinity chose not to follow the church eastward and instead held services informally before establishing their own church, St. John's Episcopal Church, in 1834. Founding members of St. John's included Ohio City pioneers Josiah Barber and George Lord Chapman, along with prominent architect Hezekiah Eldredge, who was responsible for overseeing the construction of the new church building. Under Eldredge's direction, construction commenced on July 2, 1836, with Bishop Charles McIlvaine laying the cornerstone on Church Avenue near West 26th Street.

It has been widely reported that St. John's served as a stop—it was dubbed "Station Hope"— on the Underground Railroad in the years leading up to the Civil War. According to these reports, slaves hid in the church's bell tower and watched for signals from the lake telling them that it was safe to embark on the final leg of their journey towards freedom. Leaving the church, runaways would venture to the lakeshore where they boarded steamships bound for Canada. However, some doubt is cast on these claims since they are not definitively documented and because on the national level the Episcopal Church was one of the few Protestant denominations that did not split between North and South over the issue of slavery. If the church did not take an abolitionist stance, it begs the question of who aided the fugitives. Perhaps it was founding member and longtime vestryman George Lord Chapman, who was friends with outspoken abolitionist John A. Foote along with fellow church founder and "colonizationist" Josiah Barber. Or it may have been Chapman's wife Eliza. Equally involved in the church, she was described as a woman whose "whole life had been one of active beneficence. For the poor, the sick, and needy, the orphan, the friendless her heart poured out its sympathy and love in words and works which made her beloved as falls to the lot of but few." While the church's official position regarding slavery may have been one of indifference, it does not seem likely that individuals such as the Chapmans would have been able to ignore moral issues of secular nature like slavery, a notion supported by the many reports of St. John's Underground Railroad involvement.

The Civil War years at St. John's were highlighted most notably by the marriage of prominent Cleveland politician Marcus Hanna to Charlotte Rhodes in 1864. Soon after the close of the Civil War, however, disaster struck St. John's, with fire consuming much of the church's wooden interior. Initially believed to be caused by the heater located in the basement, further investigation determined that an act of arson caused the blaze. The tragedy proved to be a blessing in many ways though, as it provided an opportunity to expand the church to accommodate an ever-increasing number of parishioners.

In 1871 longtime minister Lewis Burton resigned as rector of St. John's to lead the two missions that St. John's had spawned, All Saints and St. Mark's. Burton had held the position for twenty-four years prior to his departure, and the following year Marcus Hanna became a vestryman of the church, serving for thirty-one years until 1903, a span which included the appearance of President William McKinley as his guest on at least one occasion for services. Through the Great Depression and World War II, St. John's remained a pillar on the Near West Side, and then in 1953 a tornado devastated the church, causing significant damage to the east wall and roof. Around this time the Inner City Protestant Parish emerged as an interdenominational church, sharing the space in St. John's for a number of years before eventually being absorbed by the Episcopal congregation.

By the 1980s, the nearly 150-year-old building was showing signs of deterioration, and a $100,000 renovation project was required in order to keep it operational. At present however, St. John's is closed, with services last taking place there in December 2007. As the oldest and arguably most structurally unique religious edifice in the city of Cleveland, St. John's is not only a sight to behold but remains a place whose connection to the Underground Railroad, however ill-defined, continues to excite great public interest.

Audio

Images