Cleveland's Brookside Zoo faced a crisis at the onset of the Great Depression. With Clevelanders going hungry, the city government was faced with the decision of whether to spend its limited resources caring for and feeding zoo animals.

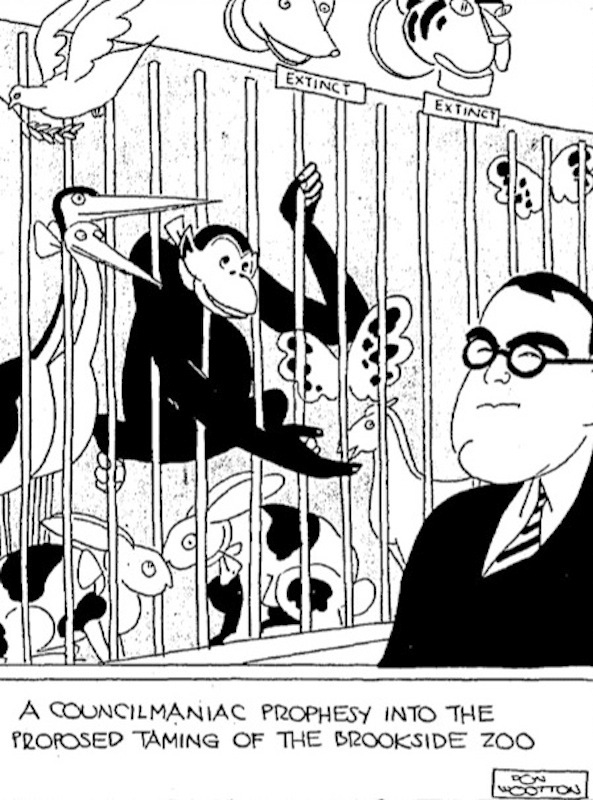

The Great Depression was a trying time in the City of Cleveland. As early as 1931, nearly one third of the city's work force was unemployed, and things would only get worse. With an already growing economic divide between suburban communities and inner city residents, the depression hit those living in Cleveland the hardest; the tax base that financed local government all but dried up, leading to a financial crisis. Public funding for institutions such as parks and libraries were heavily cut, requiring that they operate on a shoestring budget. Brookside Zoo found itself in a predicament. While maintenance of park grounds could be delayed, animals in the zoo needed food and care. The economically conservative city government was unable to provide relief within its budget; as people were waiting in food lines, the decision to provide care for animals at the zoo raised a few eyebrows. The animal population dwindled, and existing structures and exhibits deteriorated.

Despite these setbacks, the depression era marked a period of incredible expansion and growth for both the Cleveland Metropolitan Park System and the City of Cleveland's Zoo. The Brookside Zoo offered free recreation, and droves of cash-strapped city residents visited its remains. Aiding in its revitalization, federal work relief programs provided the labor needed to completely overhaul Brookside Park and Zoo. The latter would emerge the economic crisis with both a new skeleton of an infrastructure and a foundation of public support, paving the way for a period of expansion in the 1940s.

A comment by Captain Curley Wilson in 1934 concerning the shape of the public zoo summed up the depression-era state of affairs: "Sixth city-and 25th zoo -- but what are you going to do when you haven't got any money?" Beginning his work as superintendent of the zoo in 1931, plans for development of the grounds had already been stilted by a lack of available city funding. All the while, attendance and usage of the free park increased due to both the newly found free time of the unemployed as well as the cautious spending habits of those with work.

Coming into his new job, Captain Wilson was initially charged with building the zoo to be on par with established zoological gardens in the United States. Efforts to remodel a bird preserve were undertaken, but plans for new structures were soon bypassed to meet the more immediate need of feeding animals. The new superintendent was instantly confronted with the staff's inability to afford adequate security at the zoo; a seal was killed at the hands of a bottle wielding vandal, birds were shot after-hours, and four locals executed a not-so-daring break-in to retrieve a pet monkey placed in the zoo's care by local police.

Providing a bit of salt for an open wound, the shrinking zoo needed to deny donations of new animals due to the cost of their upkeep. Even when zoo advocate Laura Mae Corrigan offered a donation in 1933 of 28 animals acquired on safari in Africa, the city was initially forced to refuse the gift. While it was known that the exotic animals would be an incredible boon to the zoological garden's validity as an institution, there was no available money to cover the cost of caring for the animals. Eventually, the widow of steel magnate James W. Corrigan padded her donation with a $5000 check to provide four years worth of food for the zoo's new inhabitants. The gift from Africa would act as the highlight of Brookside's collection during the Depression era.

Beyond Corrigan's generous gift, the zoo's infrastructure expanded greatly during the Depression era. A hefty list of construction projects was undertaken at the zoo and Brookside Park, utilizing work relief programs. Under the umbrella of the WPA, the zoo was provided two new exhibits - a Sea Lion pool and Monkey Island; runs for prairie dogs, guinea pigs and woodchucks were also constructed, and the bear pits were reconditioned. The grounds were rehabilitated with new roads, a lake, animal shelters, picnic grounds, and parking lots. All in all, Brookside Park and Zoo received much in the way of attention and resources from work relief programs.

A decade of depleted funding during the Great Depression also had its adverse effects. A 1940 inspection of the grounds found that nearly every building at the zoo leaked, and needed roofing and spouting. Most structures required painting and new plumbing, fencing throughout the zoo needed repaired or replaced, and the heating plant was due for a complete overhaul. The deteriorating remnants of Cleveland's early zoo structures littered the grounds which were redeveloped by work relief laborers. As the zoo emerged from the Great Depression, this contrast in the physical landscape aptly reflected the state of the institution; pushed forward by a resurgence in popularity and the evident possibilities for further expansion, the zoo's growth was restrained by its ties with Cleveland's Department of Recreation as just one of many public spaces in the city's vast park system.

Images