It was not the first time Cleveland saw a grand scheme to reorient its downtown toward the lakefront. I. M. Pei’s conception reprised, updated, and extended eastward the early 20th-century Group Plan designed by the “City Beautiful” architect Daniel Burnham of Chicago.

In 1973, architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable described "a huge, bleak, near empty plaza with a complete set of non-working fountains and drained pools, focusing on a routine glass tower by New York architects Harrison and Abramovitz, known to Clevelanders as the 'jolly green giant.'" She lamented that the plaza was flanked by "vast, open parking lots." Huxtable was referring to Erieview Plaza and Erieview Tower, together the focus of the Erieview urban renewal project, which she derided as a "monument to everything that was wrong with urban renewal thinking in America in the 1960s." Erieview attracted more than architectural criticism. Some Clevelanders also argued that the project set back the downtown district it was intended to revitalize. Plain Dealer columnist Philip W. Porter called Erieview "the mistake that ruined downtown." Porter wasn't alone. Even in the 1960s, some downtown interests worried that Erieview, which some considered a "surrogate downtown," might siphon energy away from the downtown shopping district. Would Erieview workers continue to walk several blocks to Euclid Avenue to shop on their lunch break, or would they demand amenities in a new, self-contained city-within-a-city?

Erieview was born of the same concerns about downtown stagnation that gripped many U.S. cities by the 1950s. Pittsburgh’s Gateway Center became a national model for downtown renewal, and Cleveland leaders formed the Cleveland Development Foundation (CDF) in 1954 to emulate Pittsburgh’s Allegheny Conference on Community Development. CDF weighed whether to launch its urban renewal effort (with federal dollars matching municipal expenditures in a 2:1 ratio) in downtown in a subsidized version of Pittsburgh's privately financed downtown renewal or start in east-side neighborhoods. Local architect Richard Hawley Cutting even drew a plan, pro bono, that he pitched to CDF. Called Erie View, it featured a geometric assemblage of modernist towers and plazas along the lakefront to the east of East 9th Street. CDF, whose chairman was Republic Steel president Tom Patton, rejected that urban renewal and, in 1956, proceeded instead with another, dumping Republic Steel slag in Kingsbury Run and building the euphemistically named Garden Valley, which offered substandard housing and exacerbated residential segregation.

A succession of failed downtown projects (among them the collapse of a plan for underground parking beneath the Mall, voters' rejections of a convention center expansion, and county commissioners' denial of a downtown subway) led to a series of secret meetings in the spring of 1959. Weary of the slow pace of neighborhoods-first renewal and impatient with the CDF-commissioned $100,000 downtown plan due out later that year, CDF president Upshur Evans, Cleveland Chamber of Commerce president Curtis Lee Smith, and Cleveland Urban Renewal and Housing Director James M. Lister convened to strategize how to catalyze downtown revitalization. They consulted with Chase Manhattan Bank's David Rockefeller in the hope he might invest in Cleveland. He refused but reinforced their belief that only a large, coordinated plan was worthwhile. They turned to Newark-based Prudential Insurance to try to interest the company in a regional headquarters along Lake Erie. They too demurred.

Undeterred, the trio bypassed the Cleveland Planning Commission and went straight to Mayor Anthony Celebrezze, who saw in their idea a project he could sell. Unveiled in January 1960, the plan, christened Erieview, promised the nation's largest downtown urban renewal project, a reflection of city leaders' desire to make up for lost time. They pronounced the 125-acre renewal area (roughly bounded by the Memorial Shoreway, East 9th Street, Chester Avenue, and East 17th Street) “blighted,” sealing the fate of many small businesses and manufacturers and some single-room-occupancy hotels. The city commissioned prominent modernist architect I. M. Pei to design the Erieview plan, which looked like many other plans of its era – a Tetris board of low-slung, interlocking buildings wrapping around open plazas punctuated by taller towers. The tallest of them was plotted between East 9th and 12th Streets with an open plaza and reflecting pool. It was not the first time Cleveland saw a grand scheme to reorient its downtown toward the lakefront. Pei’s conception reprised, updated, and extended eastward the early 20th-century Group Plan designed by the “City Beautiful” architect Daniel Burnham of Chicago.

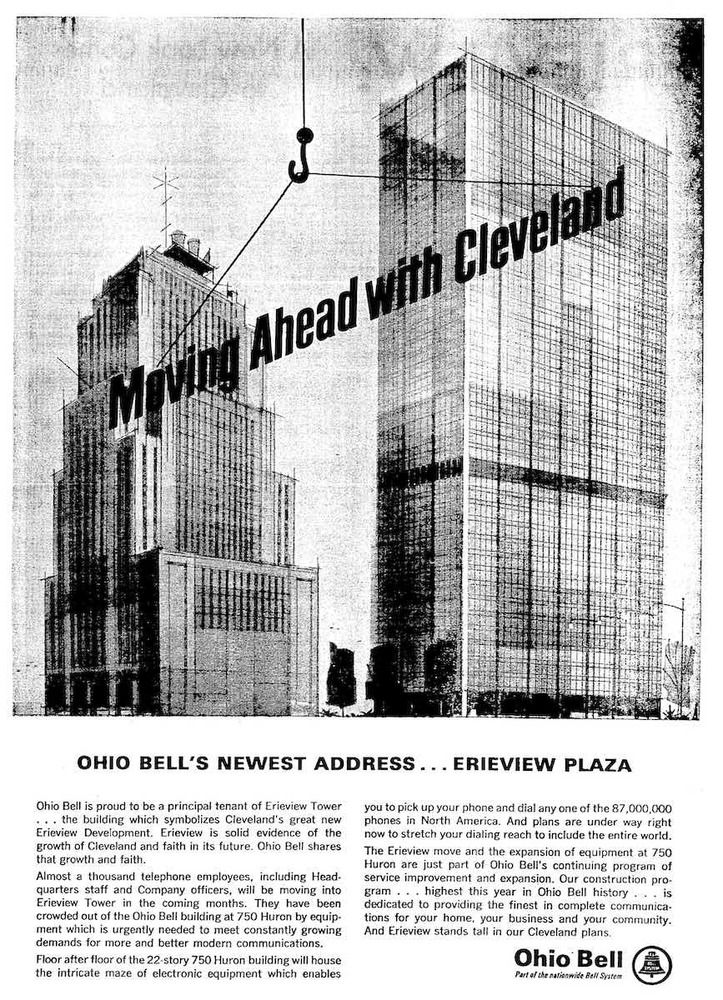

Developers John Galbreath and Peter Ruffin planned to build one or more office towers in Erieview, including the focal building at its heart. The 529-foot-tall, 40-story Erieview Tower was designed by the New York firm of Harrison and Abramovitz. Firm partner Wallace Harrison was best known for his work on Rockefeller Center and the United Nations, but the Erieview design more closely resembled the firm's 45-story Socony-Mobil Building (1956) in New York, also developed by Galbreath and Ruffin. Erieview Tower was a simplified version of its predecessor, substituting black and green glass curtain walls for black windows and silver patterned aluminum walls. Yet both buildings were later panned by some as "ugly" designs. True to its nickname, the greenish tower did loom, giant-like, over the wide-open expanse of Erieview Plaza whose fountains and reflecting pool doubled as an ice rink in winter. Widespread clearance left mostly parking lots surrounding Erieview Plaza for years.

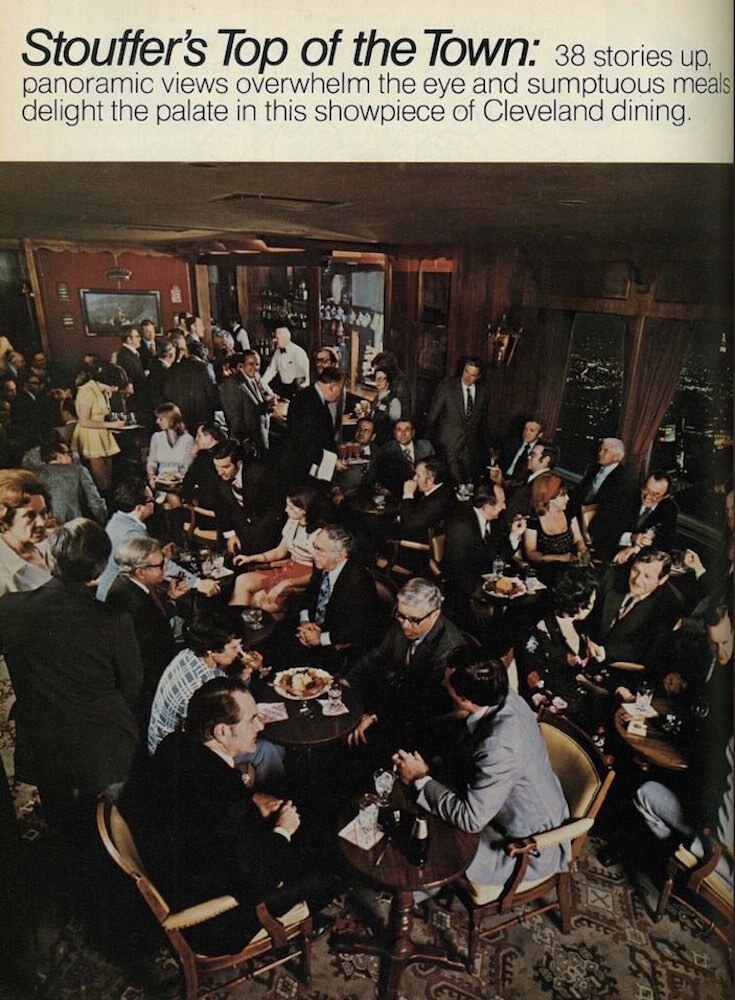

Erieview was billed as an antidote for an ailing downtown, on one hand, and as an outlet for downtown's expected office boom, on the other. While these aims may appear contradictory – one intended to reverse decline and another to accommodate anticipated growth – they actually reflected the complex situation facing downtowns in the 1960s. Suburban retail competition was causing downtown shopping to wither, but at the same time many firms were eager for more spacious, modern office space. Erieview initially spurred overdue renovations by several leading downtown department stores. That their efforts ultimately failed to save them owed less to Erieview than to the effects of population decline, suburban retail growth, and the city's failure to cultivate a strong convention trade. Office expansion promised a counterpoint to retail slippage. After Erieview Tower, the 32-story Federal Building (1967), two major hotels (today’s Westin and Doubletree) and a half-dozen major office towers, including headquarters for Diamond Shamrock (1972) and Eaton (1983), opened incrementally over the next two decades.

No sooner had Erieview been fleshed out than it started to clear out. Downtown employment dropped by one-third in the forty years after 1970, and by the 21st century the main demand was for more living space. Boosters had long predicted a return to the central city. Erieview added three apartment towers (including Reserve Square) between 1967 and 1973, but it would take another four decades before downtown became a true residential magnet, aided by conversions of old office buildings using historic preservation tax credits. In 2010, the Downtown Cleveland Alliance rebranded the Erieview area, nearly one-third vacant, as a "live–work–play" concept dubbed the Nine-Twelve District. As renovators exhausted the supply of historic buildings, midcentury properties were just crossing the fifty-year threshold to qualify as "historic." In 2018, developer James Kassouf bought Erieview Tower, newly listed on the National Register, with plans to convert twelve vacant floors into apartments. Downtown's northeastern quadrant once had hundreds of units of low-rent housing, but these held no place in the vision of Cleveland’s boosters. They yielded to civic aspirations for a new downtown of gleaming office towers. Although Erieview, recast as Nine-Twelve, is reemerging as a neighborhood, its upmarket housing inventory ensures that it can’t rightly be said to have come full circle.

Audio

Images