The Mall

When the city approved the Group Plan of 1903, it was believed that the Mall would become the city’s functional and symbolic center. The long stretch of land northeast of Public Square would turn a former slum into a parklike space, and a half-dozen neoclassical government buildings surrounding the Mall would instill a sense of civic pride and duty. These goals fit the aims of the City Beautiful reform movement, whose proponents worried that the attractiveness and dignity of American cities were being compromised by poverty, overpopulation and the perceived deleterious effects of immigration. Daniel Burnham, who played a leading role in designing Cleveland’s Group Plan, was a major figure in the City Beautiful movement. He may best be remembered for designing Chicago’s White City at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. In Cleveland, however, as Walter Leedy wrote, “Instead of a ‘White City’ the Mall turned out to be a ‘White Sepulcher.’”

The Mall’s transformation into a true city center was quashed in the 1920s by the Van Sweringen brothers’ decision to build their Union Terminal train station on Public Square, a decision that answered a federal government concern about mixing local and national rail traffic on the strategically important tracks along the lakeshore. The 1903 Group Plan specified that the city’s main train station would be built at the north end of the Mall. When that didn’t happen, it became clear that Public Square would remain the city’s center. In retrospect, this was a propitious choice: Public Square was Cleveland’s transportation hub and it was closer to the booming commercial district taking shape along Euclid Avenue. The Mall, meanwhile, became somewhat of an afterthought, used occasionally for concerts and other events but serving mainly as a cut-through for downtown workers.

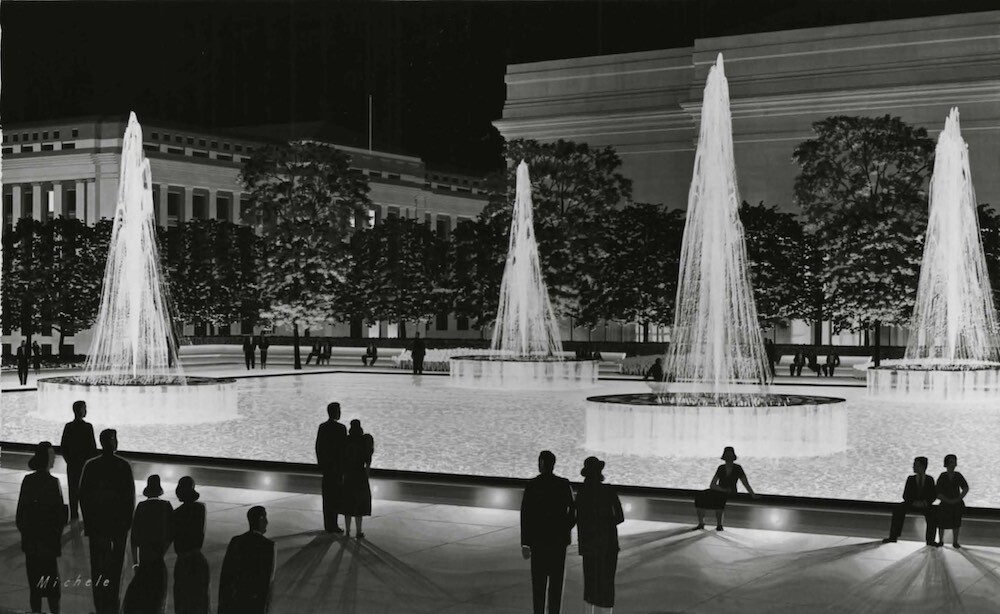

A number of plans over the years promised to inject new life into the Mall, including unrealized plans for embellishments in the late 1920s and again in the late 1930s, the short-lived amenities brought by the 1936-37 Great Lakes Exposition, a failed bid in the late 1950s for a "hotel on the Mall," and the addition of the Hanna Fountains in 1964 (but removed in 1987). In the 2010s the Mall received a new carpet of grass atop the ramp-like rise on Mall B necessitated by the most recent expansion of the convention center. New buildings, including a "medical mart" and a convention hotel were added on the Mall's western flank in anticipation of the city's hosting of the 2016 Republican National Convention. Yet the Mall still struggles to serve as a civic space, calling attention to the challenges that face all efforts to create such places.

Images