Back when Native Americans made camp along Lake Erie, Whiskey Island was a spit of high land rising out of the marshes surrounding the original mouth of the Cuyahoga River. Lorenzo Carter - Cleveland's first permanent white settler - chose this location as the site of his family farm.

Activity on Whiskey Island really picked up with the rechanneling of the Cuyahoga River in 1827. Undertaken due to the increased river traffic caused by the opening of the Ohio & Erie Canal, the straighter, man-made mouth entered Lake Erie at Whiskey Island's eastern end. The new configuration partially dried out the marshes surrounding Whiskey Island, making it somewhat more amenable to development.

Land developers soon purchased Whiskey Island from Carter's descendants and laid out a street grid on the land. Most Clevelanders still considered the area too marshy and unhealthy to consider settling there. Irish immigrants, however, who did much of the labor on both the canal and the rechanneling project, soon took up residence on Whiskey Island. The area quickly developed into a rough and tumble immigrant neighborhood, filled with saloons and slum housing. It was around this time that Whiskey Island received its name, thanks to the presence of a distillery.

Docks and manufacturing plants arrived on Whiskey Island around the same time as the Irish. By the 1850s, railroads—quickly making the canal obsolete—also began running their way across the land. By the late nineteenth century, many of the Irish inhabitants had risen in wealth and status and moved to more attractive neighborhoods. As the Irish moved away and Cleveland's industrial might grew, Whiskey Island became nearly exclusively an industrial area.

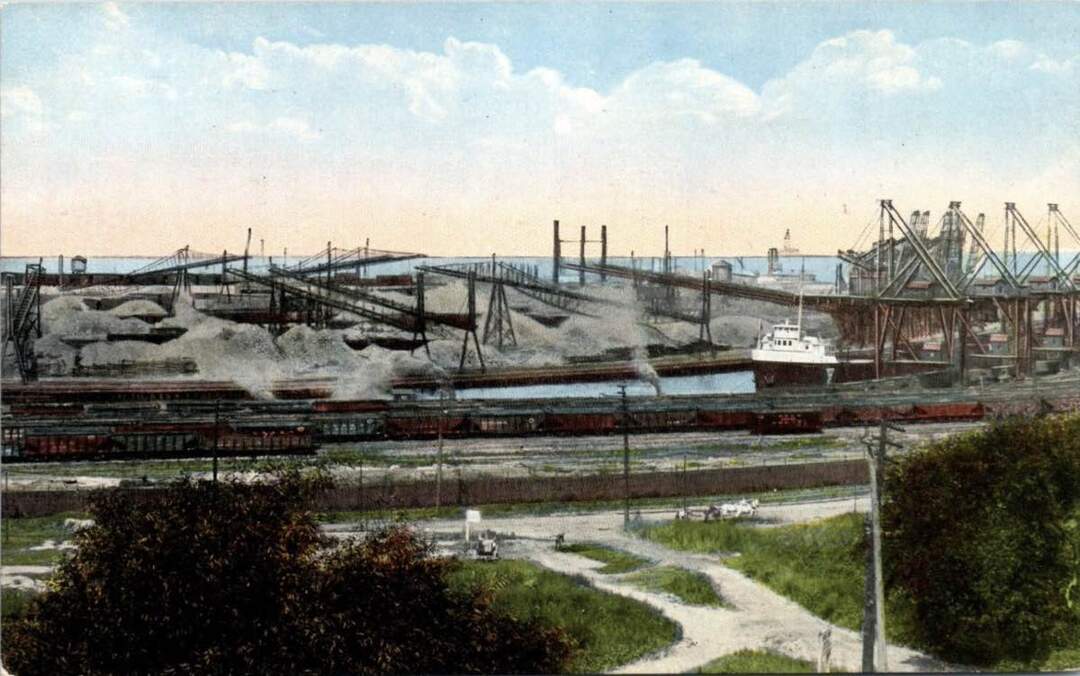

The Cleveland and Pittsburgh ore docks on Whiskey Island, which linked up with the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks running across it, featured a number of Hulett ore unloaders, named for their Cleveland-based inventor George Hulett. These 100-foot-tall behemoths had buckets that could scoop out 17 tons of ore from a lake freighter's hull in a single go. The hundreds of millions of tons of iron ore, coal, and limestone unloaded on Whiskey Island fed Cleveland's bustling industries for decades.

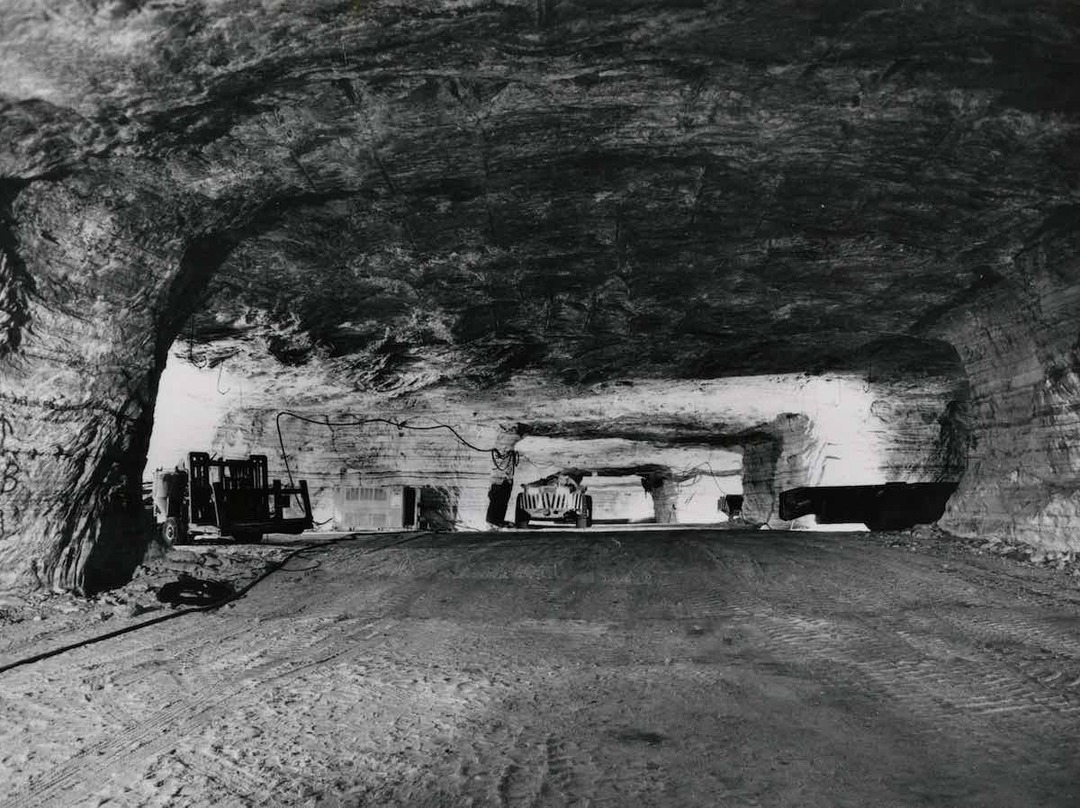

Today, the Huletts have been dismantled, replaced by self-unloading ships. The railroad tracks, ore docks, and a salt mine remain on Whiskey Island, but Cleveland's postwar deindustrialization has lessened their activity. Out of this unhappy development, though, has come something positive, as Clevelanders have reinvented Whiskey Island once again, turning its eastern end into an area for lakefront recreation. Wendy Park and the Whiskey Island Marina are yet another chapter in the story of the ever-changing Whiskey Island.

Video

Images