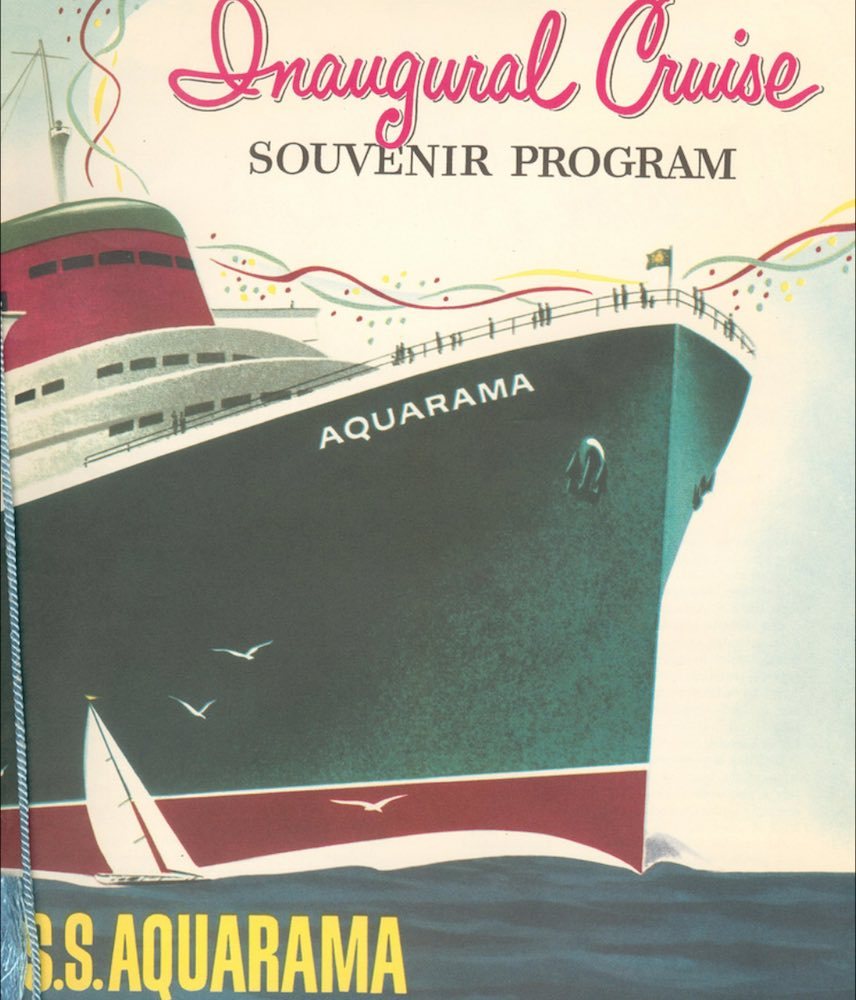

It’s 1956 and you’re a Clevelander looking for something to do. Maybe you should “make plans to come aboard the magnificent Aquarama for a memorable cruise,” as an early ad urges. Or perhaps it’s 1958 and “you are looking for an inexpensive vacation idea this summer.” If that sounds good, another ad suggests, “the luxurious lake-cruising ocean liner S.S. Aquarama may be for you.” Then again, it might be 1962 and you’re casually searching for the fountain of youth. In that case, “you’ll want to live forever on the spectacular Aquarama moonlight cruise.”

If this seems too good to be true, it isn't–or at least wasn't. Between 1956 and 1962, Clevelanders could enjoy one-day round-trip cruises from Cleveland to Detroit and Detroit to Cleveland in a “fabulous new, eight million dollar passenger ship,” according to an ad in the Plain Dealer. One day cost in 1956? $2.50 to $3.25 on weekdays; $3.25 to $4.00 on weekends. Evening cruises also were available: $4.00 for Lounge Class and $4.75 for Club Class. A trip to Detroit (or Cleveland) never looked so good. What's more, auto travelers could take advantage of what one promotional brochure touted as "A New Auto Short-Cut Across Lake Erie" which "saves 180 driving miles." Combined with another passenger/auto ferry ship–the S.S. Milwaukee Clipper between Muskegon, Michigan, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin–one could drive or ride in a virutally straight line from Cleveland to Milwaukee.

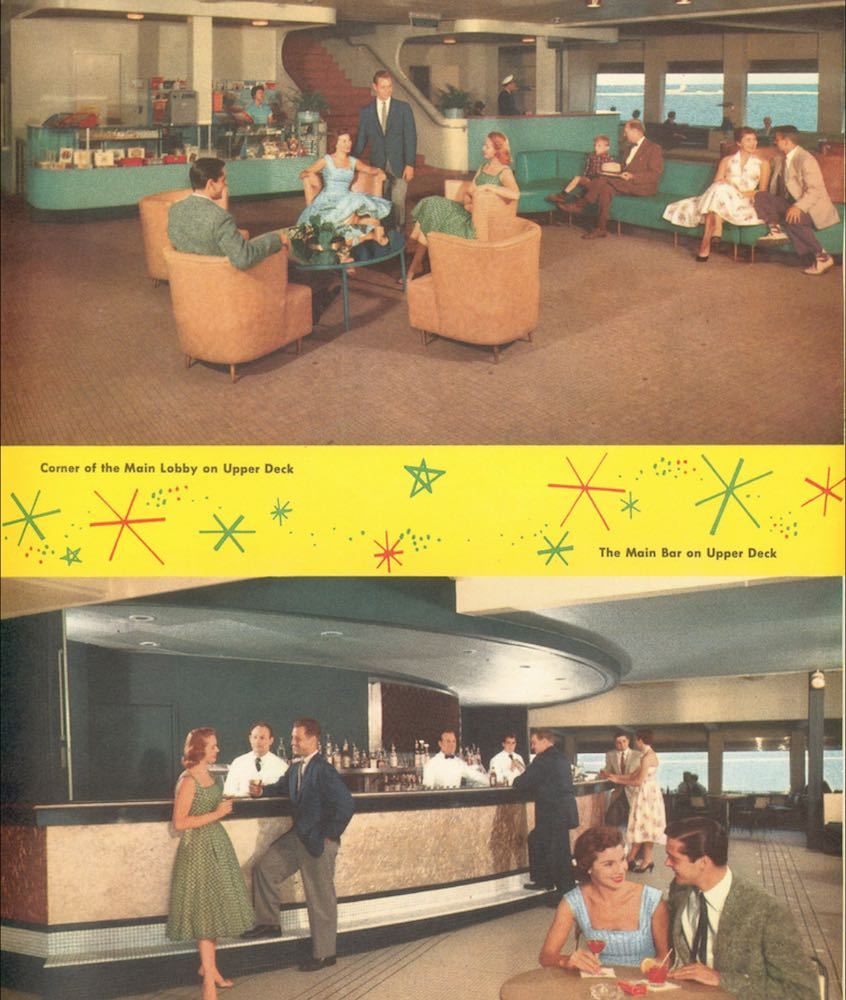

The Aquarama began its life in 1945 as a transoceanic troop carrier called the Marine Star: 520 feet and 12,733 tons. It made only one Atlantic Ocean trip before combat ceased. Eight years later, the ship was purchased by Detroit’s Sand Products Company and taken to Muskegon, Michigan, where it underwent an $8 million, two-year conversion, and was reborn as a nine-deck luxury-class ferry capable of carrying 2,500 passengers and 160 cars. The rechristened Aquarama also touted five bars, four restaurants, two dance floors, a movie theater, a television theater, and a playroom. Special events often were held in conjunction with day or evening cruises. For example, on June 10, 1962, passengers were treated to a style show from Lane Bryant’s Tall Girl Department. The next month, evening cruisers on the Aquarama could watch the Miss World finals. Regular shipboard entertainment included musical performances, dancing, marionette shows, games, and contests.

The cruise portion of the ship’s life actually began in 1955, with tours to various Great Lakes ports and a brief stint as a “floating amusement palace” docked along Chicago's Navy Pier. Soon after, service began focusing solely on runs between Cleveland and Detroit: six hours “door to door” with Cleveland-based passengers embarking in the morning from (and returning in late evening to) the West 3rd Street pier. For the next six years, the Aquarama was extremely popular but never profitable. Part of the problem may have been frequent “incidents”: One summer, the Aquarama backed into a seawall. A year later, it hit a dock in Cleveland. A week after that, it banged into a Detroit dock, damaging a warehouse. Alcohol issues also were recurrent: Accusations included untaxed booze and liquor sold in Ohio waters on Sunday. Still, the ship’s most likely death knell was simply high operating costs.

The Aquarama made its last trip on September 4, 1962. It then was towed back to where it had been rebuilt–Muskegon, Michigan, ostensibly to continue as cruise vessel. Unfortunately, a prohibitively large dredging investment was needed to accommodate the harbor. The Aquarama thus sat dockside—residing (but not operating) later in Sarnia, Ontario, Windsor, Ontario, and Buffalo, New York, where entrepreneurs hoped in vain to convert it to a floating casino. In 2007 the Aquarama was towed to Aliağa, Turkey, where it was broken up for scrap.

For a half dozen years, Clevelanders could enjoy an oceangoing experience on the Great Lakes. But neither Cleveland nor Detroit were slated to remain hot destinations. As beautiful as the open lake surely was, the decrepitude of the ends (the destinations) was less and less able to justify the beauty of the means (the travel). As a Plain Dealer editorial noted on July 4, 1956, “[the] Aquarama’s spit and polish makes you wince a bit when you look at our present lakefront. From the ship’s portholes, our port looks more like a hole.”

Images