Laid out by Moses Cleaveland's surveying party in 1796 in the tradition of the New England village green, Public Square marked the center of the Connecticut Land Company's plan for Cleveland and, soon, a ceremonial space for the growing city. In 1856, Cleveland's first fountain was constructed on the square. Four years later a statue of Battle of Lake Erie hero Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry was erected in the center of the square, leading City Council to rename Public Square as Monumental Park. In 1865, Clevelanders watched returning Civil War regiments as they mustered on Public Square, and later generations would greet returning veterans from subsequent wars. Public Square also provided a space for viewing the caskets of fallen U.S. Presidents Abraham Lincoln and James A. Garfield in 1865 and 1881, respectively. In perhaps its most notable moment in the 19th century, in 1879, Public Square garnered international attention when inventor Charles F. Brush showcased one of the world's first successful demonstrations of electric streetlights there.

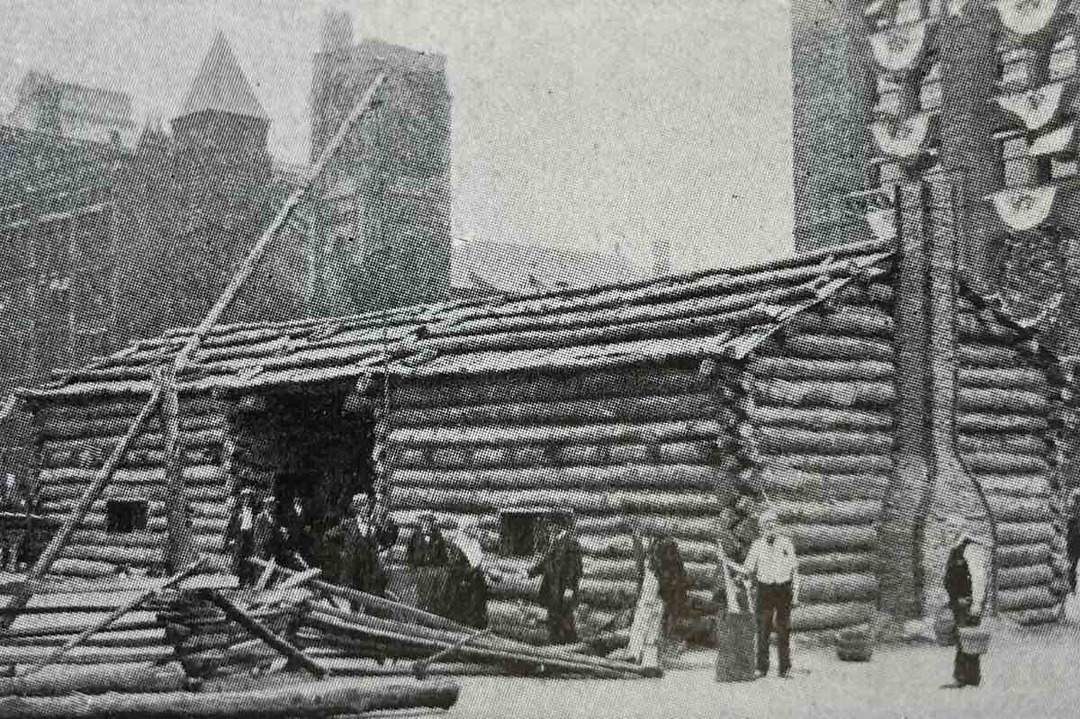

Adding to the reputation of Monumental Park, a statue of Moses Cleaveland rose on the northwest quadrant in 1888, and on July 4, 1894, the 125-foot-tall Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument was dedicated on the square's southeast quadrant in honor of Civil War veterans, at which time Perry's monument was moved, first to Wade Park. Although protests halted an 1895 plan to erect a massive new City Hall across the northern half of Public Square with an arch to permit Ontario Street traffic to pass underneath, in the following year the city marked its centennial with a large arch over Superior Avenue just east of Ontario and a replica of an original log cabin in the northeast quadrant.

In addition to its symbolic value, Public Square has also been a transit hub since the 19th century, first as a point of arrival for stagecoaches, and later as the hub of streetcar and bus lines. Traffic patterns around Public Square were a source of much controversy in the 19th century. In the 1850s, supporters of a fully enclosed square erected a fence around its entire perimeter, preventing traffic from entering. Eventually the transit demands of an expanding city won out, and in 1867 roads once again passed through the center of Public Square. Since that time, Public Square has labored under often-conflicting demands that it serve simultaneously as symbolic space, transit hub, and park. The opening of the Cleveland Union Terminal in 1930 prompted a sprucing up of Public Square, including the removal of a pavilion and a rustic bridge over an artificial stream that had occupied the square's southwest quadrant for decades. In their place was a large open lawn that provided a tidier "front yard" for the tallest building in the world outside New York. In the years that followed, transit use gradually eclipsed whatever parklike qualities the space had held.

In 1943 a new transit plan called for a new central subway station under Public Square. Ontario Street was to be depressed beneath Superior Avenue, and the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument was to be relocated elsewhere. A Plain Dealer reporter quipped that the statue's removal "alone is almost worth the cost." The 1940s and 1950s passed with no action on building a subway system. A 1958 plan proposed by architect Howard B. Cain, whose Park Building offices overlooked Public Square, envisioned closing Ontario, depressing Superior below grade, removing the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument, and creating a Rockefeller Plaza-influenced sunken plaza with an ice-skating rink. Dubbed International Square, Cain's transformation--no doubt inspired by the expanded world trade that boosters claimed the impending opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway would produce-imagined shops and restaurants representing many nations. The next year, a new downtown master plan revived the idea of a subway under Public Square, this time affecting only its southern half. The plan also called for lowering the level of the northern half of the square, moving the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument to the northeastern quadrant and building a sunken ice rink in the northwestern quadrant. Like Cain's plan, this part of the downtown plan languished when county commissioners nixed the subway project. In the wake of the subway defeat, a 1960 plan to close through streets in Public Square and construct a 1,600-car underground garage likewise failed.

Yet, the dream of remaking Public Square did not disappear. In the 1970s, urban planner Lawrence Halprin brought his imaginative renewal ideas to Cleveland. Halprin recommended turning Euclid Avenue into a pedestrian mall and remaking Public Square into a more parklike space. Iris Vail, wife of Plain Dealer publisher Thomas Vail, and other Garden Club of Cleveland women held a "Beautification Ball" in the Arcade in 1975 to raise $100,000 to finance a specific blueprint for the square. They hired Don M. Hisaka of Cleveland and Sasaki Associates of Massachusetts to design the new Public Square but then decided they did not like his minimalist, modernistic vision for the space. Instead, they spearheaded a more traditional parklike redo of the northeastern quadrant as a demonstration. Over the ensuing decade, Public Square was remade quadrant by quadrant as city, county, state, and federal funds, along with Cleveland Foundation and Garden Club monies--in all $12 million, augmented the original $100,000 raised by the Garden Club.

Opened with laser-show fanfare just in time for Cleveland's sesquicentennial in 1986, the revamped Public Square sported parklike spaces and, in the southwest quadrant, a brick and granite terraced plaza with an artificial waterfall. In maintaining Superior and Ontario as through streets, the 1980s Public Square remake fell well short of decades of visions for reuniting the four isolated quadrants. In 2002 the New York-based Project for Public Spaces visited Cleveland and urged reunification of the square, calling it one of the world's most dysfunctional public spaces. Mayor Frank Jackson's appointed Group Plan Commission, a blue-ribbon committee inspired by Daniel Burnham's famed "Group Plan" of a century before, set out to make both the Mall and Public Square reach their potential as appealing destinations for locals and visitors. The commission approved a plan by James Corner, known for his innovative High Line project, which transformed an abandoned elevated railroad in New York City into a linear park. With the announcement of Cleveland's selection to host the 2016 Republican National Convention, civic leaders rallied to raise the $32 million needed make the long-awaited reunification of Public Square a reality.

Audio

Images