The Cleveland Catholic Worker

Personalism, Prayer, and Community on the Near West Side

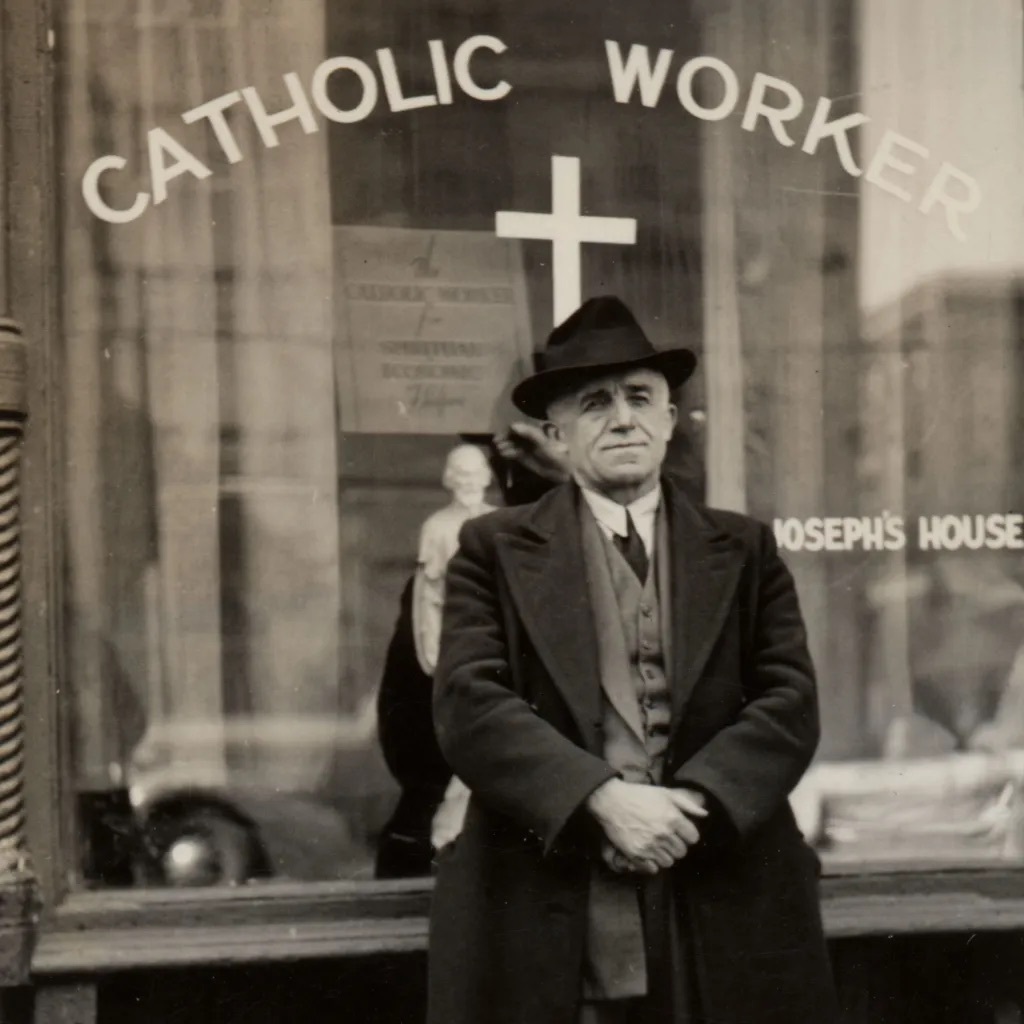

In 1933, Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin co-founded the Catholic Worker newspaper, which laid the groundwork for the Catholic Worker movement in the United States. The Catholic Worker was priced at “a penny a copy,” and continues to cost a penny today. The paper was crucial in spreading awareness about social issues that affected those who were struggling in the United States. From the Catholic Worker movement's inception, Day and Maurin highlighted the importance of personalism, prayer, hospitality, and community. In Maurin's “Easy Essay,” an early article in the Catholic Worker, he emphasized, “The Catholic Worker believes in creating a new society within the shell of the old with the philosophy of the new, which is not a new philosophy but a very old philosophy, a philosophy so old that it looks like new.”

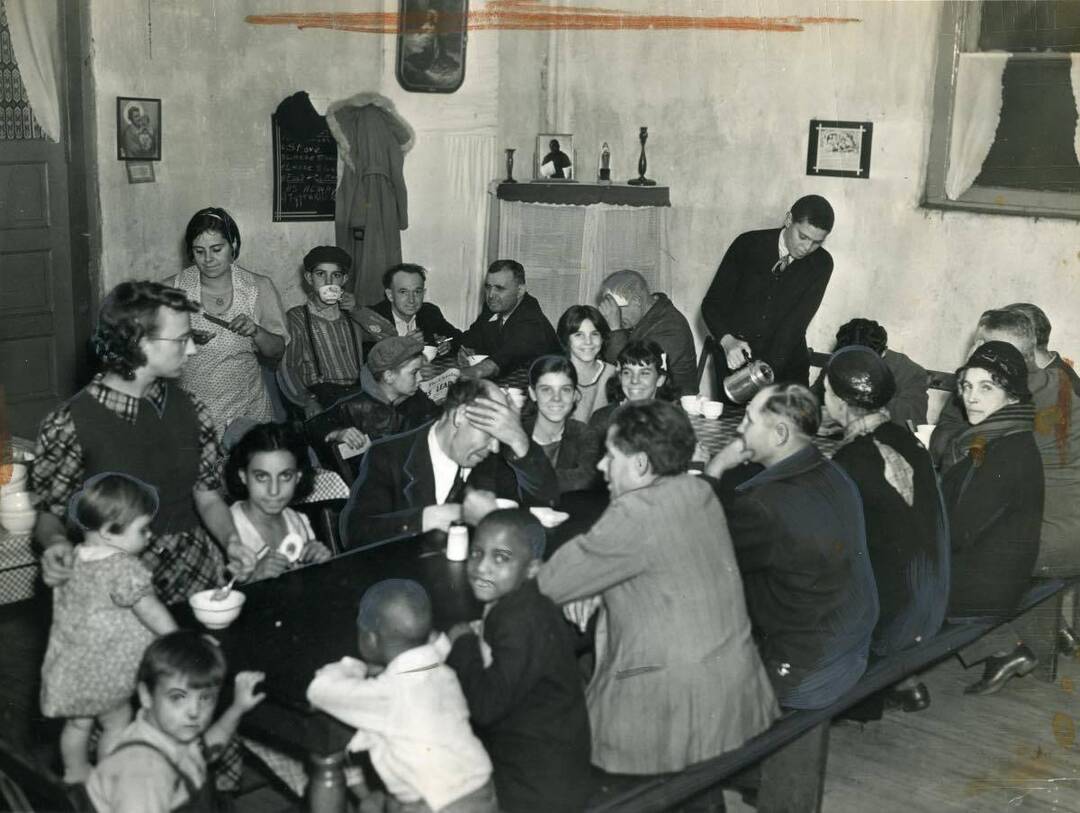

Houses of Hospitality within the Catholic Worker community have been crucial in providing lodging and meals for many in need. Houses of Hospitality are similar to Progressive Era settlement houses, which aided the poor as well as recently arrived immigrants. Like settlement houses, Catholic Worker Houses of Hospitality allow those living there to be an active part of the community while living and interacting with those in need of support.

By the 1980s, several Catholic Worker Houses of Hospitality and communities had emerged nationwide. In 1984, several figures, which included longtime residents Bill and Judy Corrigan, Jim and Patty Schlecht (Sullivan), along with a recent newcomer from Mishawaka, Indiana, Joe Lehner, formed the Cleveland Catholic Worker to live out the philosophy established by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin. In 1986, a group of Catholic Workers on Cleveland’s Near West Side considered locations in the neighborhood where they could build community and witness the Gospel through word and deed. As Cleveland’s Catholic Worker grew, there was a need for a location to broaden the hospitality offered to the community, specifically for unhoused people in the area. The need for hospitality became a topic of discussion among the core members involved.

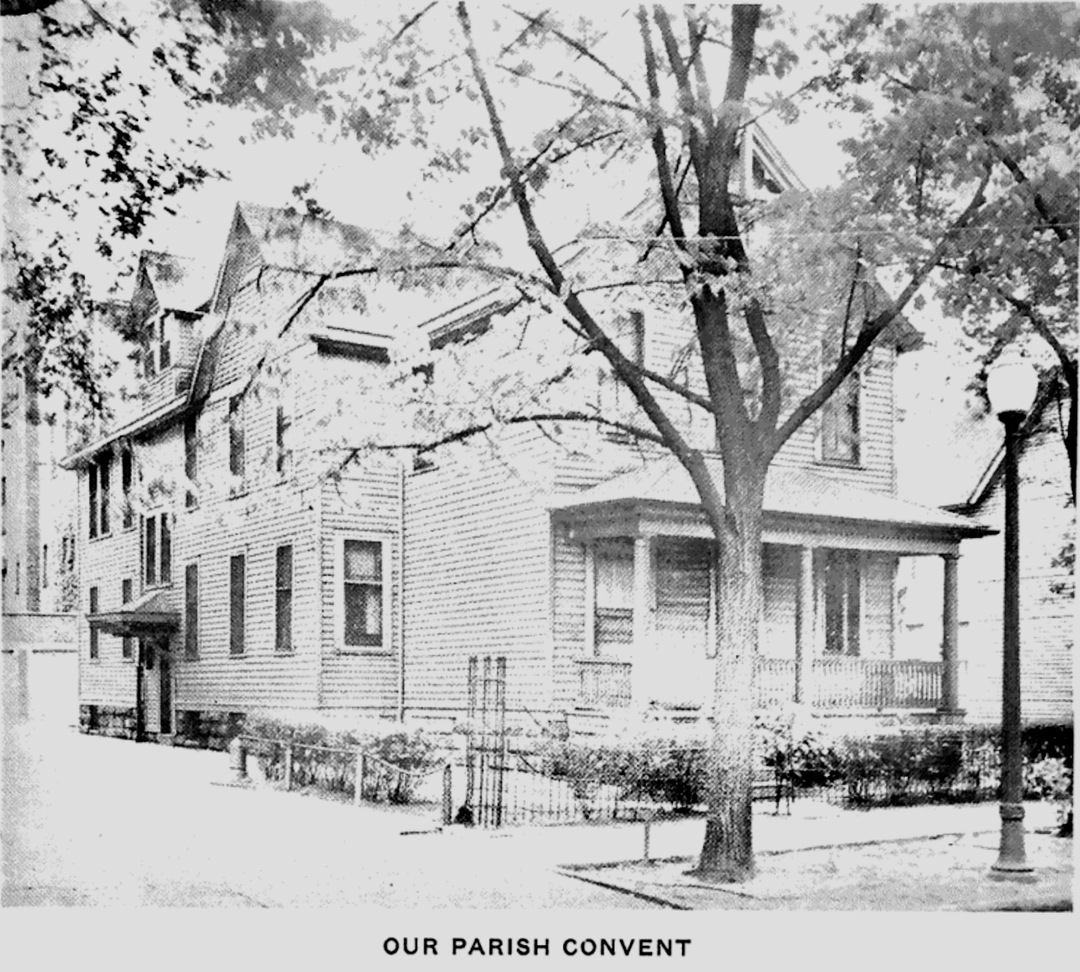

Dennis Sadowski, Jim Doherty, and Jim McHugh, three Catholic Workers, had been discussing living in community and were pivotal in the foundation of Cleveland’s Catholic Worker House of Hospitality, located at 3601 Whitman Avenue. The house offered a central meeting spot for many of Cleveland’s Catholic Workers, but before it was the Whitman House it was known as the “Mission House.” The Mission House was purchased by Saint Patrick Parish in 1873 and became the home for Marianist Brothers who taught at Saint Patrick’s School. Other groups such as the Ursuline Sisters, Jesuit volunteers, and Marianist volunteers stayed in the Mission House before the Catholic Worker.

Throughout the summer of 1986, various core members prayerfully weighed the pros and cons of living in community. In the end, they agreed that living in community opened them to be vulnerable to the basic questions that called them to a belief in Jesus. They knew they had to overcome the barriers that often keep people from middle-class backgrounds from encountering people living on the margins of society.

After several meetings and discussions with St. Patrick’s Father Mark DiNardo, they made an agreement that the Catholic Worker would rent the former Mission House in the names of Sadowski, Doherty, and McHugh for $200, not including the utilities. In October 1986, Sadowski, Doherty, and McHugh, along with two unhoused gentlemen living on the streets, John “Hugh” Fee and John “Whitey” Pavlison, officially moved into the Mission House. The Mission Home then assumed a new name, Whitman House, that forever marked the Cleveland Catholic Catholic Worker’s presence in the neighborhood. In the years to come, many individuals would find community, prayer, and a source of shelter within the walls of this former convent.

Sadowski was the first to leave the house in 1987 after living there for roughly four months. Doherty lived there for 15 months, leaving in January 1988, and McHugh stayed until about 1990. Fee remained at the Whitman house until 2002, when he passed away. The date when Pavlison left and his whereabouts remain unknown. Throughout the years, the Whitman House provided a place for many generations of Catholic Workers to meet, live, eat, and engage in meaningful prayer and dialogue.

Cleveland’s Catholic Worker began publishing a quarterly periodical, Inherit the Earth, in the late '80s. Inherit the Earth invited members of the Catholic Worker to contribute to the paper through articles, poetry, artwork, reflections, photography, and even recipes. Many of the articles focused on updates in the community from Catholic Workers, young and old. Each quarterly paper also included the community mission statement, which stated, “We are forming a loving and caring resistance community with a strong spiritual base which will enable us to share our lives with those who are broken, not just for their benefit, but ours as well, knowing that we are all sisters and brothers.” Many of the articles in this periodical emphasized the community's resistance to war through political and social commentaries written by members. Nonviolence is one of the aims of a Catholic Worker. Resisting the Cleveland National Air Show has been pivotal in the Catholic Worker’s protest against war. Through their pacifist resistance, Cleveland’s Catholic Worker hopes to inform and educate the public about the real purpose of the planes flown for entertainment each Labor Day.

For many years, each Inherit the Earth issue included an update on the Community, which kept everyone in the loop on events and individuals living in the Whitman House and the extended Catholic Worker community. In the early 2000s, Whitman House struggled to maintain stable live-in volunteers. It was not until 2004 when multiple volunteers joined the Catholic Worker and lived in community that the house started to pick up with live-in Workers. In the fall of 2004, one Catholic Worker provided an update on the Whitman House and introduced nine Catholic Workers living there at the time. These introductions, full of inside jokes about the Worker's hygiene, give readers a glimpse of the friendships made while living together and forming close bonds through the volunteer work in which they all were involved.

In January 2009, a meeting was called to discuss the continuance or possible relocation of the Catholic Worker from Whitman House. St. Patrick, which was the landlord of the Whitman House, had been included in a Cleveland Catholic Diocese–proposed merger with three other Near West Side churches — St. Malachi Parish, Community of St. Malachi, and St. Wendelin Parish. This meeting was called and functioned democratically to address any misunderstanding and to discuss the pros and cons of living at the Whitman House or relocating elsewhere. This meeting highlighted the importance of the Whitman House being conveniently located near necessary services and Catholic Worker operations. This meeting also focused on the importance of landlord-tenant relations between the Catholic Worker and who they decide to rent from, whether that be St. Patrick or a new landlord.

Ultimately, the Cleveland Catholic Worker decided to relocate. This move was a three-year-long process. Although much smaller than the Whitman House, the new house at 2082 Fulton Road opened at full capacity with nine live-in volunteers in 2012. The Fulton House celebrated its tenth anniversary in 2022. This milestone brought Catholic Workers who lived there at the time together with workers who once lived in both Whitman and Fulton House in prior years. A special edition of Inherit the Earth came out that fall to commemorate the move to Fulton House. This edition included many photographs of Catholic Workers, young and old, current and former, and also included photos of the extended community.

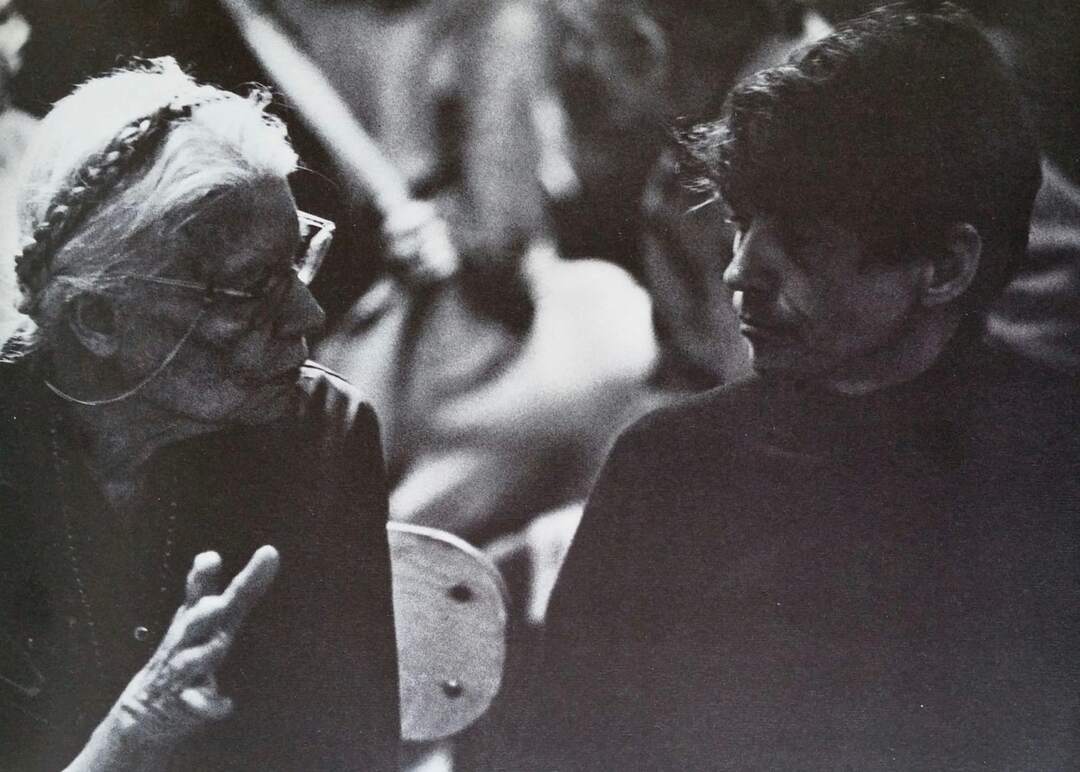

The ten-year celebration of Fulton House gave an understanding of the community that has formed on Cleveland’s Near West Side. Catholic Workers celebrated the lifelong bonds they had made with one another and the awareness they had spread on issues regarding war and poverty, along with the importance of nonviolence. From the teachings of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin in the early 20th century, their philosophy of personalism, prayer, and ultimately love have been a part of Cleveland’s Catholic Worker community for forty years.

Images