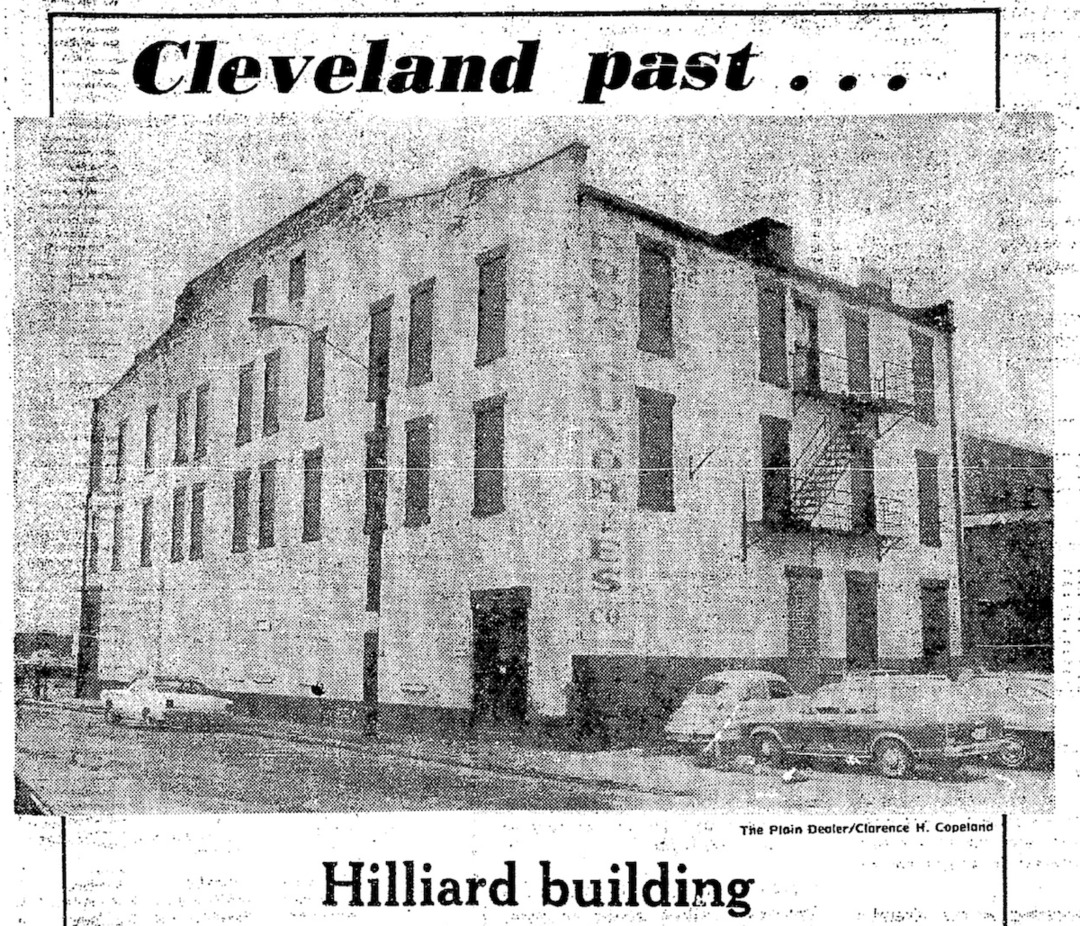

Hilliard Building

The Oldest Commercial Building in Downtown Cleveland

Richard Hilliard achieved much as a businessman and civic leader in the thirty years (1826-1856) that he lived in Cleveland. Most of his achievements have long since faded from the public's memory. However, the three story brick building that he erected in 1850 still stands today on West 9th Street as a reminder to Clevelanders of who he was.

In Cleveland's Warehouse District, northwest of Public Square, the historic Hilliard Building stands on the corner of West 9th Street and Frankfort Avenue. A visitor to the area can't help but notice how isolated it is from other buildings. In fact, it is entirely surrounded by parking lots. There is a parking lot to the west of it, directly across West 9th Street. There is another to the south of it between Frankfort and the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen Building on Superior Avenue. And finally there is a very large parking lot that extends north from the Hilliard Building all the way to St. Clair Avenue and also to the east behind the building all the way to West 6th Street.

Such parking lots, when covering large areas of a city's downtown, have become known as "parking craters," a term popularized by blogger Angie Schmitt who wrote that they render urban landscapes "inhospitable and unattractive." How and why the Hilliard Building came to occupy such an isolated location on West 9th Street, in the middle of a "parking crater," is an important part of the history of this building.

The Hilliard Building is named after Richard Hilliard, who was born in Chatham, New York in 1800. When he was a teenager, Hilliard began working in dry goods stores in western New York. One of those stores opened a branch in Cleveland in 1824, locating its new store at the southwest corner of Water (West 9th) and Superior, across Superior from where the Western Reserve Building stands today. Two years later, Hilliard who had by then become a partner in that business, moved to Cleveland. He soon bought out his partner and then formed a new partnership with William Hayes, a dry goods merchant in New York City. At about the same time that they formed their partnership, Hilliard married Sarah Katherine Hayes, a sister of his new partner, not an unusual way to cement a business relationship in the nineteenth century.

The dry goods business of Hilliard and Hayes, according to Hilliard's biographers, soon became very successful, and Richard Hilliard developed into an important figure in Cleveland's early history. In 1830, he was elected President of the Board of Trustees of Cleveland Village, and in 1836, when Cleveland became a city, he was elected one of its first aldermen. In the decade of the 1830s, he was one of the developers of Cleveland Centre in the Flats, a bold, but ill-fated, effort to make Cleveland the center of international trade in the Midwest. In the 1840s, Hilliard and Henry B. Payne, became more successfully involved in the incorporation of the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad, Cleveland's first railroad, both of them becoming directors of that railroad. (Payne, an attorney, later built the Perry-Payne Building on Superior Avenue in downtown Cleveland.) In the early 1850s, Hilliard served as the first president of the Cleveland Water Works Commission, which led to the creation of Cleveland's first public water works system in 1856.

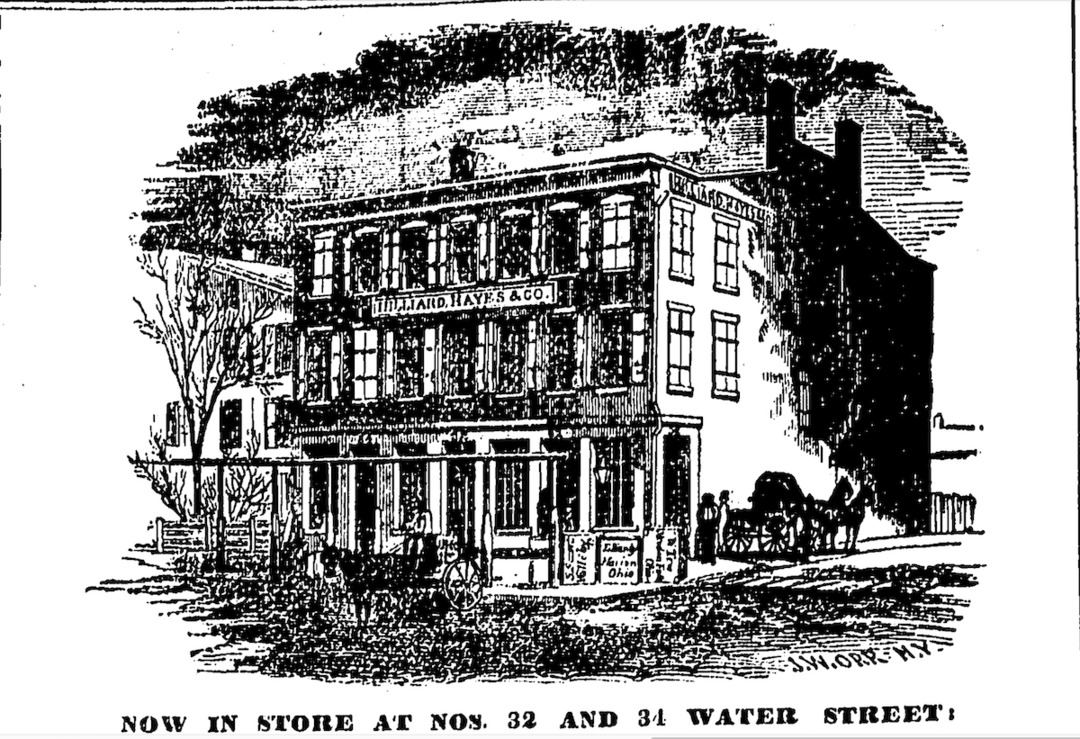

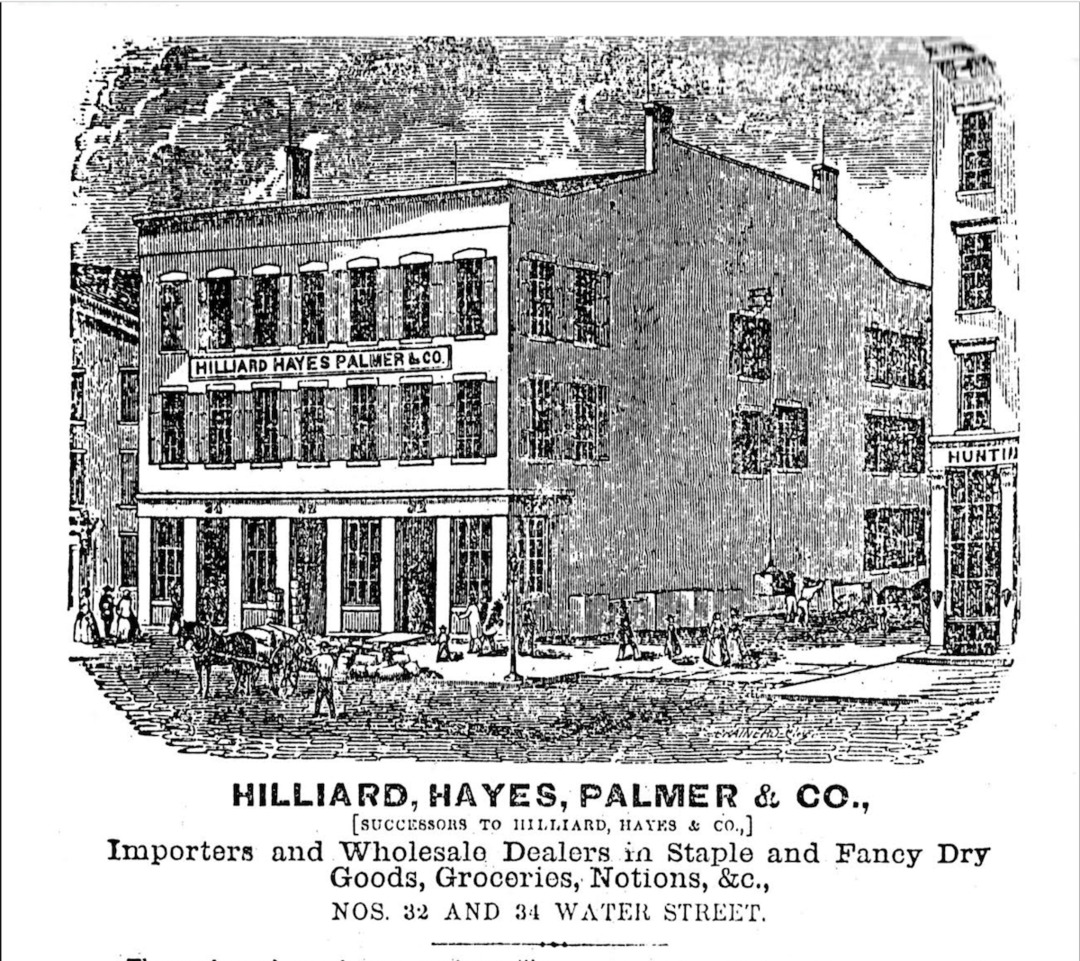

In 1850, Hilliard built the three story brick commercial building which is the subject of this story, moving his dry goods business into the building in the same year. According to an article appearing in the Plain Dealer on June 27, 1851, the building had 48 and 1/2 feet of frontage on Water Street and 100 feet on Centre (today, Frankfort) Street. The interior of the building was arranged as follows. There was a dry goods room measuring 25 by 100 feet on the Centre Street side of the building, and rooms on the two upper floors of the building that were also used in the dry goods business. The balance of the front of the building consisted of a room approximately 21 by 80 feet which served as a grocery store. The rear 20 feet of that part of the building was "furnished and used as a Counting-room."

Hilliard and Hayes, which then became Hilliard, Hayes and Co., was, according to newspaper sources, the largest dry goods wholesale business in the Midwest in the 1850s. It provided dry goods to retail stores in Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin, and had sales that annually exceeded $500,000, equivalent to almost $20 million in 2024 dollars. However, shortly after returning from a business trip to New York, Richard Hilliard died on December 21, 1856 from typhoid fever. He was only 56 years old. His death had a profound effect upon his wholesale business operated out of the Hilliard Building, then known as the Hilliard Block. Several new partnerships were formed with combinations of Hilliard's son Richard Jr. and several of his father's former partners, but none lasted. On March 22, 1858, an advertisement appeared in the Plain Dealer, offering the "stock . . . business and good will" of the company for sale. By 1860, a new wholesale dry goods firm, S. Raymonds & Co., was operating its business out of the Hilliard Block.

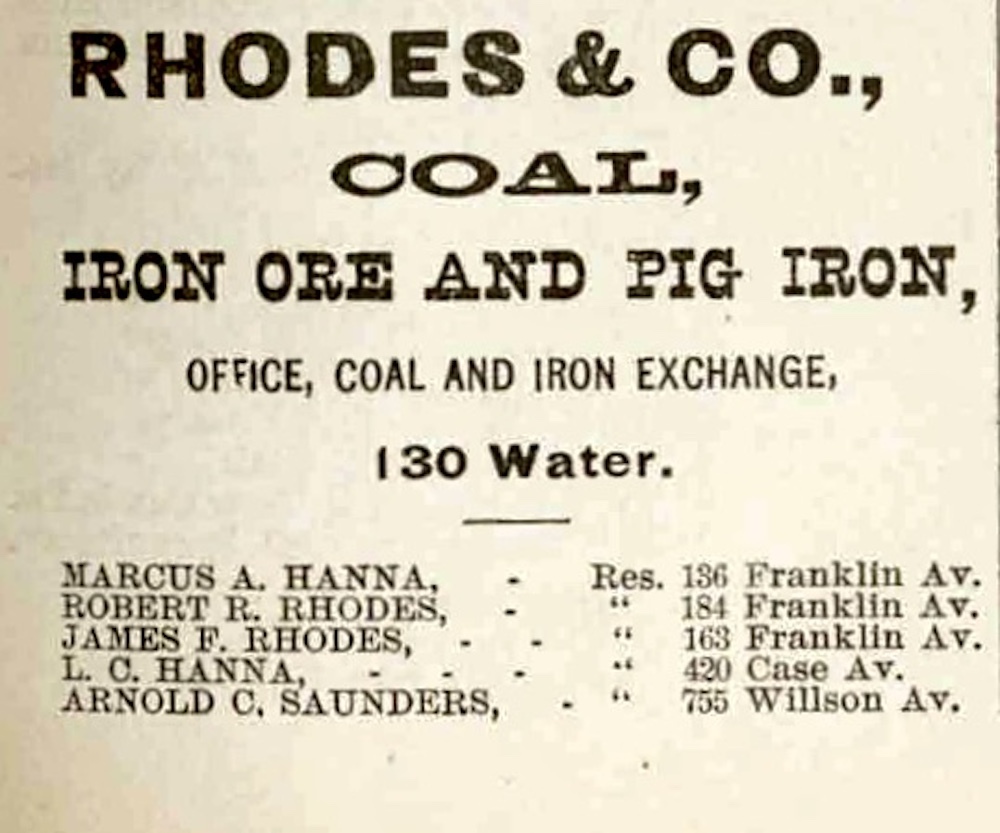

S. Raymond and Co. occupied the Hilliard Block as a tenant for more than a decade under leases from the Hilliard family who still owned the building. Then, in 1875, the building took on new tenants when it was remodeled as an office building for merchants in Cleveland's coal and oil trade. Among those new tenants in the building now known as the Coal and Iron Exchange Building was Rhodes and Hanna, a business started by prominent early west side industrialist Daniel Rhodes, but, following his retirement in 1867, operated by a partnership that included his son Robert Russell Rhodes and son-in-law Marcus Hanna. (Known to history as "Cleveland's kingmaker," Hanna later directed the successful 1896 and 1900 presidential campaigns of William McKinley.) From 1875 to 1887, a number of Cleveland's most prominent coal and iron merchants had their offices in the building.

In the mid to late 1880s, as new and grander commercial buildings were erected in the Warehouse District like the Grand Arcade (1883) and the Perry-Payne Building (1889), coal and iron merchants left the Hilliard Block for these more prestigious addresses. For a time, the Hilliard building then served as home to the offices of several stocks, grains, provisions and oil brokers. In the early 1900s, several related wholesale fire equipment and marine supply companies operated out of the building. In 1914, Laura Hilliard, the youngest daughter of Richard Hilliard, who had owned the Hilliard Building since the 1880s, sold it to Koblitz Brothers Realty Company, who, under several different corporate names, owned and leased it to various tenants until 1950.

During the 1920s, when Koblitz Brothers owned the Hilliard Building, the Warehouse District, according to local historian and archivist Drew Rolik, reached its pinnacle of commercial development and then began a slow decline as some of its aging buildings were, beginning in the mid 1920s, demolished to make room for parking lots. At first these new lots were few and far between, but the pace of parking lot creation increased following the end of World War II and the building of the interstate highway system which facilitated a massive movement of urban dwellers to the suburbs in the post war era.

In the 1950s, government officials like County Engineer Albert Porter advocated for more parking lots in downtown Cleveland to encourage suburban residents to come downtown to work and shop. His sentiments were echoed by business leaders like Alfred Benesch who, in a letter published in the Plain Dealer on April 21, 1957, wrote that the Warehouse District (then known as the Wholesale District or as part of the Garment District) was an ideal location for such parking lots as it was filled with "buildings a hundred or more years old . . . which are not any asset to Cleveland . . [and] might be well condemned and razed in order to provide parking facilities . . "

With encouragement like this from government and private sector leaders, the pace of building demolition and parking lot creation in the Warehouse District increased in the 1960s and 1970s. However, in the latter decade the tide began to turn as preservationists made their voices heard. In 1977, aided by a report from architect William A. Gould, the Cleveland Landmarks Commission adopted a comprehensive preservation plan for the Warehouse District. Five years later, in 1982, with the Commission's urging, the City of Cleveland created the Warehouse Historic District, which was later accepted and added to the National Register of Historic Places. By 1988, the Landmarks Commission felt comfortable in proclaiming victory for the preservation of the District.

According to Stephanie Ryberg-Webster in her book Preserving the Vanishing City, by the time victory was declared, more than a third of the buildings that were standing in Cleveland's Warehouse District in its peak year of 1921 had been demolished. The result was the creation of a number of "parking craters" in the District, including the earlier mentioned one within which the Hilliard Building still stands today. That crater began to form in the 1930s when a number of buildings on Frankfort Avenue between West 9th and West 6th were torn down, as well as a part of the Payne Brothers Building on the southeast corner of West 9th and St. Clair. In circa 1950, the old W. Bingham building across Frankfort from the Hilliard Building was torn down for a parking lot, and, as that decade progressed, more buildings were torn down on Frankfort, as well as a number on the west side of West 9th across the street from the Hilliard Building.

The decade of the 1960s and 1970s saw additional buildings demolished on the west side of the West 9th Street, many of them as the result of fires of unknown origin. And then, perhaps most notably for the Hilliard Building, one by one the buildings that lined the east side of West 9th immediately north of the Hilliard Building and south of St. Clair Avenue were demolished for parking lots. The remaining part of the Payne Brothers Building was the first to go in 1966; the Vincent Block next door to it then was torn down in the 1970s; and finally the Board of Trades Building, the last building standing on that side of the street between St. Clair and the Hilliard Building, in the 1980s. By the time the dust settled and the Cleveland Landmarks Commission declared victory in stemming the tide of demolition, the Hilliard Building was left in the middle of the parking crater that it still occupies today, almost 40 years after victory was declared.

The Hilliard Building avoided the fate of the other nineteenth century buildings that once surrounded it, most likely for two reasons. First, in 1950, the building was purchased by two brothers, Sidney E. and Albert E. Saltzman, who, during the peak years of demolition in the Warehouse District, operated a successful wholesale business called Drug Sundries Co. out of the building. And second, in 1983, after the tide had turned toward preservation rather than demolition in the district, attorneys Stanley Yulish and Mark Twohig purchased the building from the Saltzmans; renovated and restored it; and moved their law firm into the building.

Since 2000, the Hilliard Building has been owned by several different limited liability companies, and in 2020 it was further renovated and remodeled in order to convert the second and third floors of the building into apartments. Now, in 2024, almost 175 years old, the Hilliard Building is not just downtown Cleveland's oldest commercial building. It is also a remarkable survivor of the second half of the twentieth century in this city when, for a time, parking in the Warehouse District was king.

Images