On its opening day in January 1961, Sheraton-Cleveland’s Kon-Tiki restaurant welcomed more than 2,000 visitors to Cleveland's first new Tiki bar in twenty years. Whether they were tired of a dreary Cleveland winter or were simply interested in the city’s newest restaurant, these visitors experienced what many could never have imagined, an exotic Polynesian paradise just off Public Square in downtown Cleveland.

In late 1933 former bootlegger and globe traveler Ernie Gantt opened the world’s first Tiki bar in Hollywood, California, naming it “Don the Beachcomber.” Gantt decorated the interior with masks, totems, and idols he collected during his Polynesian adventures and served his exotically named, high-strength rum cocktails to an enthusiastic post-prohibition crowd. Soon after opening, the laid-back island vibe and convenient location just off Hollywood Boulevard drew the attention of Hollywood stars looking for an alternative to the stuffy and formal nightclubs of the era, causing the bar’s popularity to skyrocket. Word of the Beachcomber spread, causing countless imitators to open copycat bars. The most notable was Vic Bergeron’s Trader Vic’s in Oakland, California, which invented many Tiki mainstays like the Mai-Tai and Crab Rangoon.

Seven years after Gantt opened the Beachcomber in Hollywood, Sammy Brin introduced Tiki to Cleveland by opening Club Zombie inside the Hawley House Hotel on West 3rd and St. Clair. Featuring tropical-themed decorations with fake palm trees disguising the supporting columns and split-bamboo-covered walls, Club Zombie quickly became Cleveland’s most popular nightclub and laid the groundwork for the Kon-Tiki and other Tiki bars across the city.

Tiki’s popularity rose exponentially following World War II when veterans who returned home from the Pacific spread stories and memories of the tropical shores they enjoyed while on leave. They and those who grew weary of their daily routine looked to Tiki, which allowed them to temporarily escape their daily grind to a distant, imaginary tropical paradise for a drink or two at happy hour or a backyard cookout. Another reason for the rise of Tiki was the excitement regarding the addition of Hawai’i as the 50th state in the union. Tiki culture emerged and evolved into a distinctly American blend of the global sounds of Exotica music, westernized Chinese food, Caribbean rum, and Polynesian-inspired décor that dominated American culture in the mid-20th century.

In 1958 the Sheraton Corporation purchased the four-decade-old Hotel Cleveland on the southwest side of Public Square for $10 million and embarked on a $5 million renovation and modernization project. An essential part of the project was a 3,000-person capacity ballroom atop a large parking garage designed to entice suburbanites to return to the downtown nightlife scene. The second significant aspect of the project was the closure of Hotel Cleveland’s flagship restaurant, the Bronze Room. For over forty years, the formal and stately Bronze Room allowed politicians, executives, and other high-echelon Clevelanders to dine and dance in luxury; however by the late 1950s, consumers began to want more than just a meal when they went to a restaurant. They now wanted an exciting and entertaining experience, and the stiff and formal atmosphere of the Bronze Room offered little to these new discerning patrons. In response to this nationwide shift in consumer demand, Sheraton’s management partnered with former actor Stephen Crane, owner of Hollywood’s standout Tiki restaurant the Luau, and replaced the aged Bronze Room with the third restaurant in a new, national chain of Tiki restaurants named Kon-Tiki. This new chain joined two other major Tiki chains, Don the Beachcomber and Trader Vic’s, and soon every major American city would host at least one Tiki bar.

Sheraton named the Kon-Tiki chain after the primitive balsawood raft that explorer and anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl used to travel over 4,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean in 1947. Heyerdahl’s voyage atop his raft, the Kon-Tiki, was an experiment hoping to prove his radical theory that refugees fleeing South America arrived and populated Polynesia rather than migrants sailing from the Asian mainland. Heyerdahl’s voyage on the primitive raft enraptured the American public, who kept apprised of his progress via long-range radio transmissions. The book and subsequent documentary film he produced about the trip became a massive success, topping Cleveland’s bestseller list in 1950, eventually selling over fifty million copies in more than seventy languages.

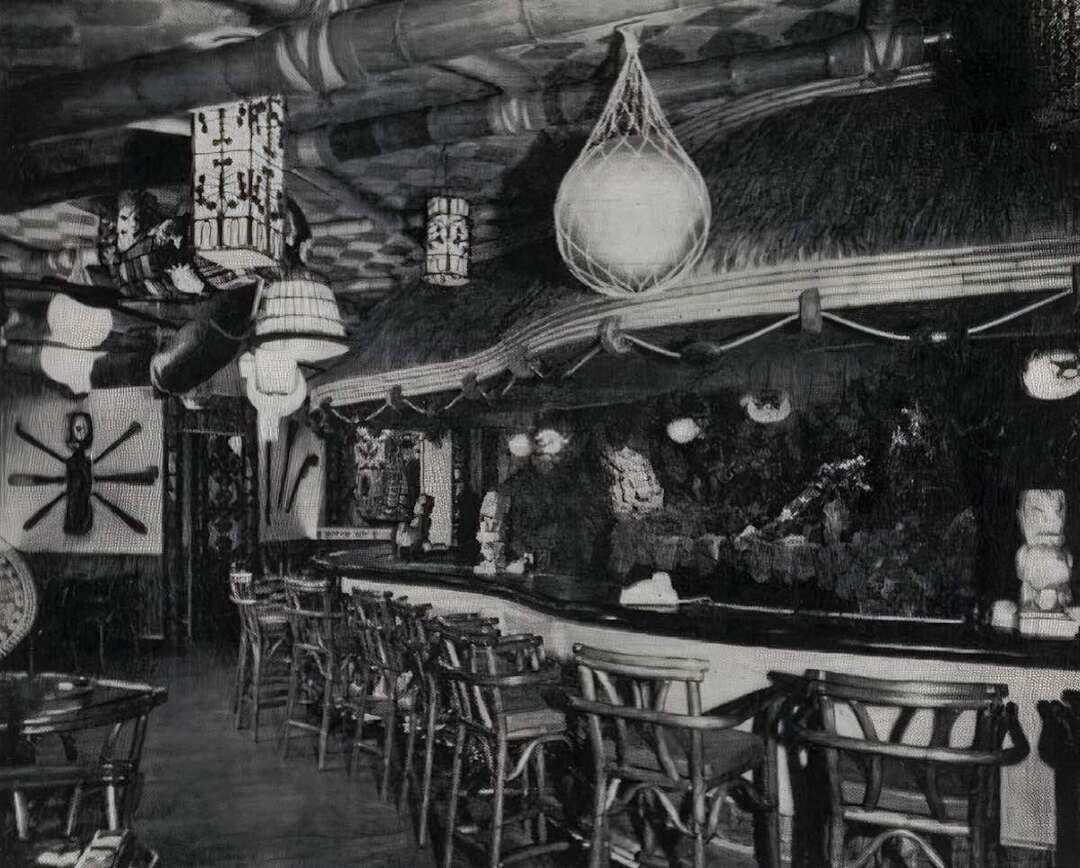

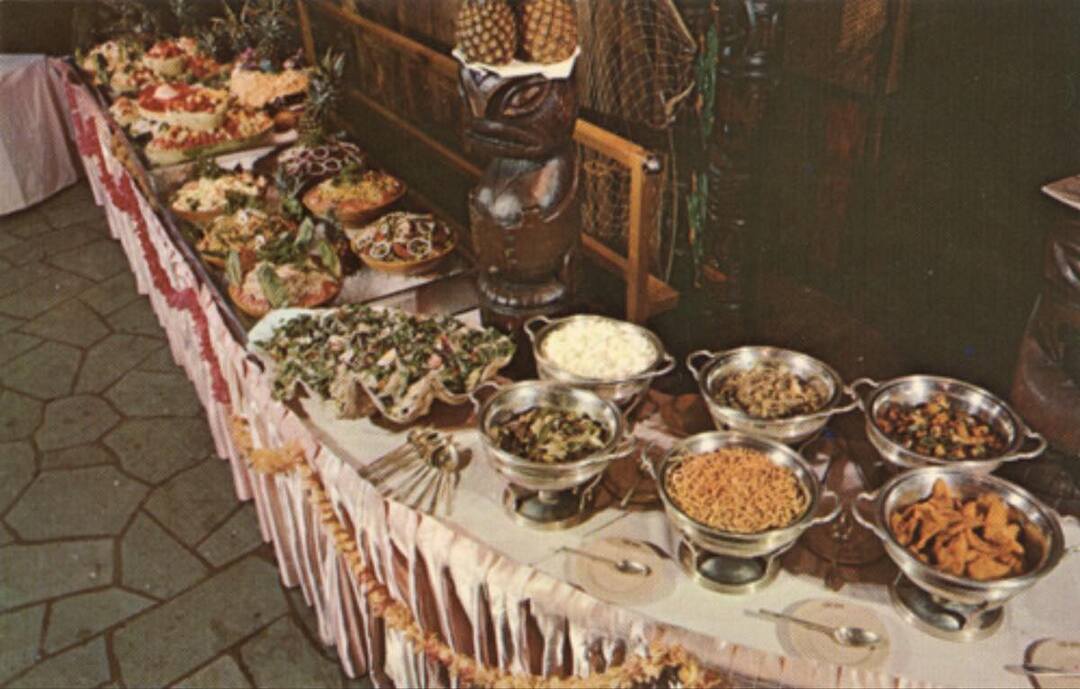

On January 23, 1961, the 230-seat Kon-Tiki restaurant opened its doors, welcoming Cleveland to the Tiki heyday. Keeping with the idea of an exciting dining experience, Crane designed the restaurant with the diner’s experience in mind. After passing through the large wooden doors beneath the prow-shaped awning, guests waiting to be seated had their view of the restaurant’s dining room obstructed by panels and rock-lined walls; this allowed their anticipation to build and lent an aura of mystery to the restaurant. When it was time to be seated, guests went to one of six individually themed rooms after crossing a running stream that fed rock-lined ponds from a waterfall and a wooden bridge with intricately carved balusters featuring Tiki idols. Whether they sat at the bar in the Aikane room, the intimate patio room, or the large Māori Long Hut with room for fifty, diners at the Kon-Tiki would experience what, at the time, people considered an authentic Polynesian atmosphere while eating dishes with exotic names such as opiopioi moa, kalua maia, laiki, kihapai, and omaomao prepared by a chef brought in from Hong Kong.

The food menu was undoubtedly important, but the cocktails set the Kon-Tiki apart from competing restaurants. Drinks such as the Tahiti, Luau Grog, Zombie, Jamaica Sangaree, and Guatemala Cooler showcased Tiki’s international influences, while their vague descriptions in the menu ensured patrons would experience the unknown. The drinks served by the Kon-Tiki were a blend of house-made syrups, fresh fruit, and various spirits served in unique mugs, stemware, and hollowed-out pineapples that distinguished them from traditional American cocktails. Adding to the entertaining atmosphere, some were even lit aflame before being presented to the customer.

Tiki resonated in American pop culture mainly because of its sense of escape. However, the late 1960s ushered in the arrival of jet-powered passenger planes that offered an actual escape to a tropical island. Additionally, worldwide decolonization struggles and the increased availability of modern media began to educate the American public that Tiki’s agglomeration of so many distinct cultures masked a more sobering reality. A group of white men developed Tiki culture by taking sacred symbols from peoples across the world, using them as mugs to hold cocktails. They did so while yearning for a wholly manufactured version of a culture that just a few generations earlier had been the target of a campaign of cultural genocide led by missionaries and imperial powers to force “civilization” onto the island inhabitants and now was a target for nuclear tests, military occupations, and hordes of tourists.

The Kon-Tiki closed its doors in early 1976, portending the end of Cleveland’s Tiki era until the resurgence of high-quality crafted cocktails led Stefan Was to open Porco, now Cleveland’s only Tiki bar on West 25th that, like other modern tropical bars, has shifted away from cultural exploitation while retaining the focus on well-crafted fruit-based drinks. Was managed to find the wooden exterior doors and other decorations from the Cleveland Kon-Tiki and incorporated them into Porco’s interior design. As fate would have it, patrons who are looking for a well-crafted tropical drink pass through the very same doors that welcomed 2,000 curious Clevelanders to the Sheraton-Cleveland Kon-Tiki more than sixty years ago.

Images