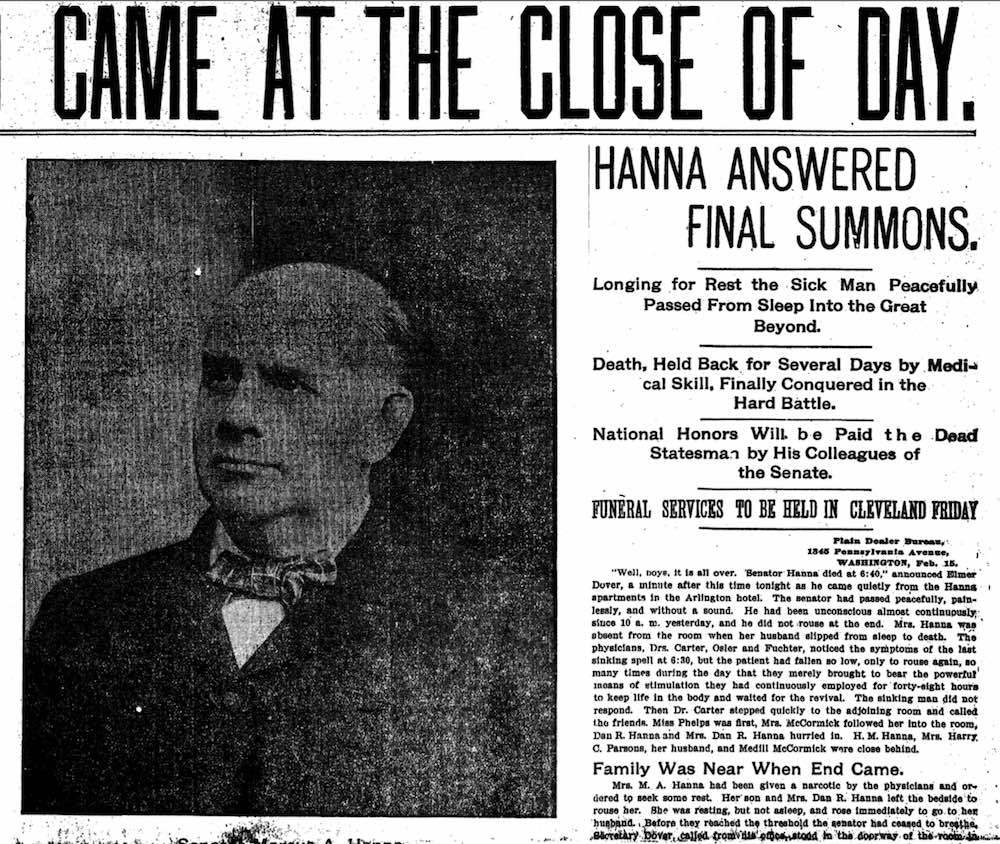

The Hanna Building was named after the famous U.S. senator from Ohio and oil and coal baron Marcus Alonzo Hanna and built by his son Daniel Rhodes Hanna. Hanna is perhaps best known for having endorsed William McKinley for president in 1896, spending $100,000 of his personal funds to support McKinley's campaign. McKinley won the election, and as a token of gratitude, McKinley aided Hanna in becoming a senator. Hanna's bronze bust is a prominent feature in the building's lobby.

The building, whose architect was Charles A. Platt, was built from 1919 to 1922, cost $5 million, and occupied land that previously held the Euclid Avenue Presbyterian Church at the corner of East 14th Street and Euclid Avenue. The building's unique interior featured a semicircular lobby with entrances on both streets and stylized silver-and-gold decorative elements. The building's restaurant on the first floor was fashioned in a beautiful Pompeian style, and the rest of the building was used for offices. It is said that the building contained all the variety of businesses required to build a city and maintain it.

The Hanna Building of the 1920s demonstrated that Cleveland had its own version of Broadway. The building opened around the same time that the Playhouse Square movie palaces started operating, and its restaurant catered to Jazz-Age theater goers and nightlife seekers. As much as it served the emerging entertainment scene, the Hanna Building was an anchor of business. Soon after opening, it ranked second in Cleveland in elevator use with 8,223 people using its lifts on a single day when a citywide count was taken.

The 1930s were a difficult time with the building losing half of its value and much of its occupancy. The average vacancy rates for office buildings nationally before and during the Great Depression were 8% in 1926, 12% in 1929, 20% in 1932, and 28% by 1934. The situation at the Hanna was so bad at one point that the owners contemplated turning the building into a warehouse before reconsidering. The Hanna Building Corporation also reduced the Cleveland Railway Company's rent from $123,000 to $108,000 in 1930 as an incentive to keep the company as a tenant. However, in the second half of the 1930s, vacancy began to decrease to 11.4% by the end of 1938 and the situation began to stabilize. So while the Hanna saw an increase in vacancy during the early 1930s, by the end of the 1930s vacancy rates declined to just above the national average of 10%. T.W. Grogan became the building's manager by 1939 and would later become its owner.

In contrast to the holding pattern of the 1930s, the 1940s saw new improvements, with the Hanna Building receiving ten brand-new elevators costing $600,000 and taking slightly more than eighteen months to install. The new elevators symbolized a renewed faith in economic development and growth. By 1951, the Hanna reached peak occupancy at 98%, making that the most prosperous year for the building since it opened. Furthermore, T.W. Grogan became the building's owner after purchasing it for $5 million in 1958.

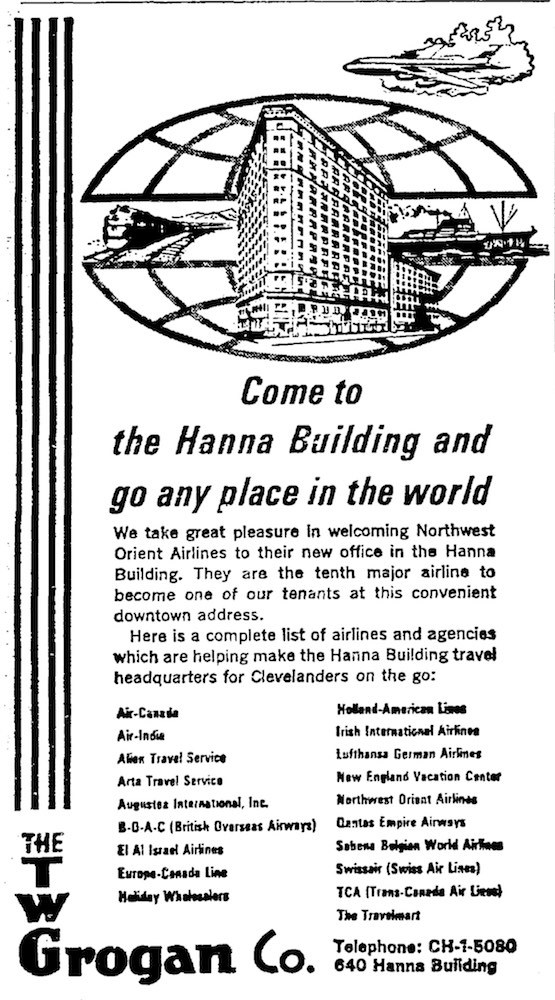

The 1960s saw the Hanna Building become the unofficial travel capital of the area. This is due to the rise of commercial jets, which were much faster than commercial aircraft driven by props and thus became popular very quickly. In the early 1960s, the T.W. Grogan Company adopted the slogan "Come to the Hanna building and go any place in the world." By 1967, travel related companies had a combined 25,000 square feet of office space out of a total 247,000 square feet, which meant that these firms had the largest amount of office space rented by any group of related businesses. By the end of the decade, the building was home to 16 airline offices, 5 travel agencies, 2 car rental agencies, a steamship line office, and even a Vermont tourist information center.

Although Cleveland's downtown was beginning to decline as a business hub, the Hanna continued to enjoy attentive ownership. In 1980, the building was modified with the original light fixtures that it was supposed to have but was never outfitted with due to Daniel R. Hanna's divorce. In 1985, Cuisines took over the Hanna Pub restaurant on the first floor and decided to return the restaurant to its original Pompeian style as a result of a newfound appreciation for 1920s-style architecture. The first floor of the Hanna Building always had a restaurant with the Hanna Restaurant being there in the 1920s, followed by Monaco's in the 1930s. The Continental Room and Child's in the 1940s, Clark's in the 1950s, The Hanna Pub in the 1960s, and finally Cuisines. With each switch, the restaurant's style was changed to reflect the decade but now it was back to what it was when it was first built.

The Hanna Building was built almost a century ago, with the intention that it would be an office building, which it remains to this day. Many office buildings built around the same time as the Hanna have been transformed into hotels or apartments in recent years, but apart from the transformation of the Hanna Building Annex to apartments, the Hanna is used for the same purpose that it was built to serve. Such continuation is a testament to the building's maintenance, as it was never left to deteriorate and lose its attractiveness for offices. With so many downtown properties having been converted to other uses, it seems that the Hanna, now owned by Playhouse Square Real Estate Services, appears well-positioned to retain its longtime focus as demand for downtown offices begins to rebound.

Images