The Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers had never before had a leader quite like Warren Sanford Stone. In 1910, with Stone at the helm as their Grand Chief, the Brotherhood built the 14-story Engineers Building on the southeast corner of Ontario Street and St. Clair Avenue in downtown Cleveland. It was the first skyscraper in the country built by a union. That might have been achievement enough for most men, but Stone was just getting started.

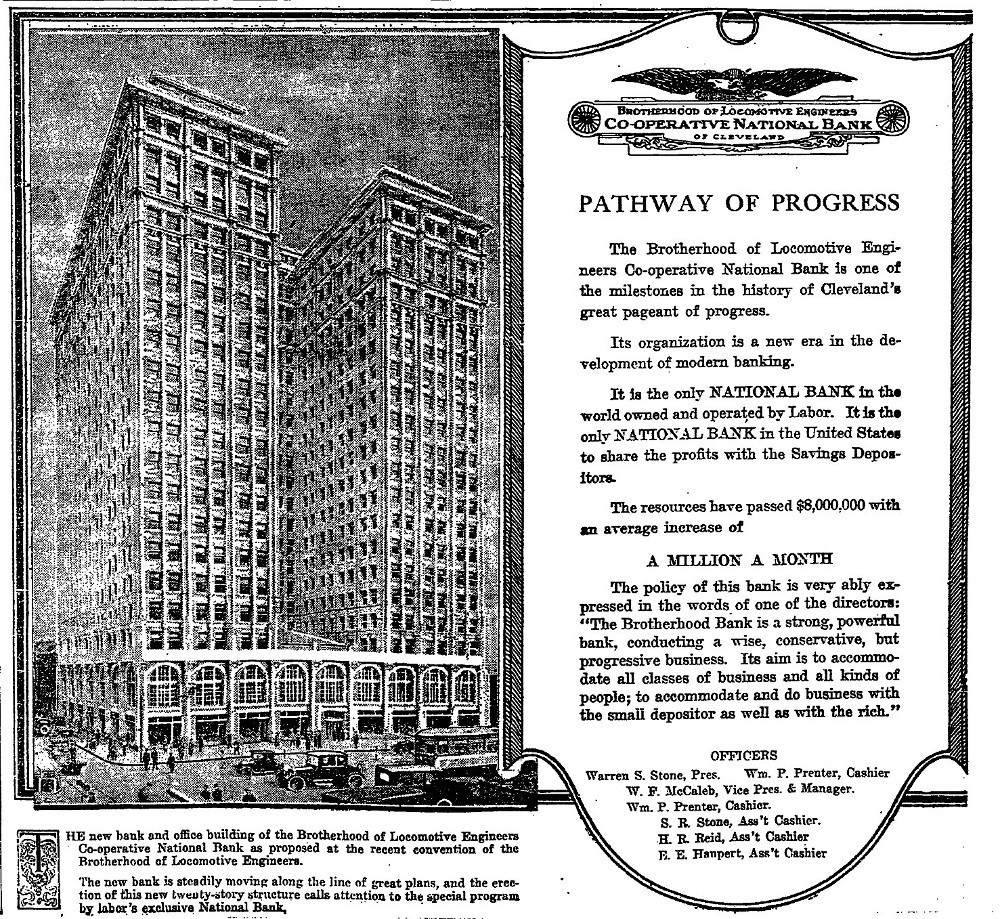

On July 20, 1925, its formal opening was held. The Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (BLE) Bank Building--known to us today as the Standard Building. That beautiful 21-story pale cream terra cotta building located on the southwest corner of Ontario Street and St. Clair Avenue, in downtown Cleveland. Built by the union whose name it originally bore and designed by the well-regarded architectural firm of Knox and Elliot, whose other works included the Rockefeller Building (1905), the Hippodrome Theater (1908), and the Engineers Building (1910) downtown, and the Breakers Hotel (1905) at Cedar Point. At 282 feet, it was taller than any other in Cleveland to that date, except for the Union Trust Building (in 2022, the Centennial Building), at the corner of Euclid Avenue and East Ninth Street. And even that building--also with 21 stories-- was only 7 feet taller.

The opening of such a building should have been a festive event for the BLE, which had been headquartered in Cleveland since 1870. The union claimed the distinction of being the oldest in the country and, with 80,000 members, it was also one of the largest. And, since 1903, it had been led by one of the most capitalist--yes, capitalist--union leaders ever, Warren Sanford Stone. In 1910, under his leadership, the union had constructed the 14-story tall Engineers Building just across Ontario Street from where the BLE Bank Building would go up 15 years later. It was the first skyscraper in the country built by an employee organization. Ten years later, in 1920, the BLE, again, with Stone at its helm, founded the country's first labor bank. Officially incorporated as the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers National Cooperative Bank, it was from the start known to all simply as the Engineers Bank. And then, in the first five years following the founding of that bank, Stone, who also served as its president, opened 15 branch offices in cities all across the country, including New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Minneapolis and Portland, Oregon. By 1925, the BLE was invested in banks, real estate, businesses and other holdings with a total value in excess of $150 million, a huge figure in that era. When asked why he had led his union into so many capital ventures, Stone responded, "When there is trouble the owners have been inaccessible to us. They were to be found on Wall Street, no matter where the [rail]road in question was located. So we decided to buy into 'Wall Street.' Now we can sit at the same table with these men and talk things over."

And now Stone's growing labor bank was preparing to move into its new headquarters in the second tallest building in downtown Cleveland. And so, by all accounts, July 20, 1925 should have been a festive day. But the mood that day was not, because Warren Sanford Stone, Grand Chief of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers since 1903 and the driving force behind all of these capitalist projects, had one month earlier, after returning from a business trip to New York, died suddenly on June 12 from kidney disease. His death had been mourned not just by union members, and not just in Cleveland, but, according to newspaper accounts, all across the country. So tragic a loss it was that the opening of the union's new bank building, which had been scheduled to open in June, was delayed to July 20. The crowd that turned out for the rescheduled event was still a large one as originally expected, but, as one reporter noted, many who attended first stood for a moment in the bank lobby of the building, gazing up reverently at the large portrait of Warren S. Stone, before moving on to see the rest of the building.

In the early years of the Engineers Bank Building's history, the bank itself occupied the two-story skylighted lobby and mezzanine in the center of the U-shaped building, as well as the basement. The next 18 floors held a variety of government and private sector tenants. The federal Treasury Department had offices on the sixth floor, and for several years Elliot Ness, who was investigator in charge of the Alcohol Tax Unit in Cleveland, had an office in the building before Mayor Harold Burton hired him to become the city's Safety Director in 1935. Other prominent tenants in the building over the years included Dyke College, Sherwin Williams, and the U.S. Army Induction Center. From the start, many lawyers also had offices in the building because of its proximity to the County Court House and City Hall, both located on Lakeside Avenue. (The number of lawyers in the building later grew even more when, in 1976, the massive Justice Center complex opened just across the street on the northwest corner of St. Clair Avenue and Ontario Street.) The 20th floor of the building originally featured a glass-enclosed garden and promenade, as well as a "sky-top" restaurant, ballroom and health club. Ness was known, even as Safety Director, to return to the health club from time to time to play a very competitive game of badminton.

It was in the 1930s that the building acquired the name by which it is known today. When the Engineers Bank merged with several other small banks in 1930 to form the Standard Trust bank, the building was renamed the Standard Trust Building. However, as so many other banks did during the Great Depression, the Standard Trust Bank soon failed, and the building then became known simply as the Standard Building. It was so known until 1974 when it was renamed the Northern Ohio Bank Building after the bank that opened offices there. However, that bank went out of business in 1975, and, on January 1, 1976, the building reverted to the name, Standard Building. It has been known as that ever since.

In 1989, the Standard Building became the headquarters of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen (BLE-T), the successor organization to the BLE, the original owner of the building. The union had been headquartered in the Engineers Building across Ontario Street since 1910, but had been forced to move from that building in 1989 when the building was razed in order to make room for the Key Center complex. The BLE-T kept its headquarters in the Standard Building until 2014, when it moved to its new headquarters in Independence, Ohio, and sold the Standard Building to a subsidiary of Weston Inc., a local real estate development firm owned by the Asher family. Weston soon announced that it planned to convert the Standard Building, which was designated a Cleveland Landmark in 1979, into a luxury apartment building to be known as "The Standard."

Images

Date: 1928

Date: 1971