The Cleveland Circulation War

When Competition between the Plain Dealer and the Leader Turned Deadly

On November 21, 1914, Thomas Gibbons, a switchman employed by the B&O Railroad, was shot dead near the intersection of West 75th Street and Detroit Avenue on Cleveland's West Side. It was the culmination of a more than one year-long circulation war between two of the city's leading newspapers that had now suddenly turned deadly. Was Gibbons an innocent bystander or did he get exactly what he deserved? Well, in 1914, that all depended upon whose newspaper you were reading.

In a business where circulation numbers have historically counted for nearly everything, there was probably never any love lost between the Cleveland Plain Dealer and the Cleveland Leader. The Plain Dealer--a partisan Democrat paper, was founded in 1842. The Leader--founded a decade later, became the Republican counterpart when, in 1859, fiery Edwin Cowles became its editor. In the years that followed, the ideological competition between the papers took on a personal dimension as the editors often exchanged barbs, including this one which appeared in an article reprinted by the Leader in 1876: "When the snarling, ill-conditioned editor of the Cleveland Plain Dealer gets drunk and falls out of the third story window of his boarding house, people in the street who catch a glimpse of his florid face and sanguinary hair cry out: 'Behold, that blazing meteor!' " In 1885, the competition, if anything, intensified, when the new owner of the Plain Dealer, Liberty Holden, began publishing a morning edition in direct competition with the Leader.

It wasn't long after these competitive foundations of the relationship between the Plain Dealer and Leader were formed that the twentieth century arrived, ushering in a period that has been called Cleveland's "golden era of journalism." The two rivals were just two of the city's six dailies--not to mention the numerous weeklies and ethnic newspapers, all of whom were vying for the attention of the city's reading population. The situation for these newspapers soon reached critical mass and some sought new methods to improve their bottom line, or to at least stay in business. One was merger. In 1905, the number of dailies operating in the city was reduced to four when the Cleveland News was created from the merger of three of the dailies. Then, Dan R. Hanna, the son of the late Republican kingmaker Marcus Hanna, employed a different type of merger. In 1910, he purchased the Leader and then purchased the News two years later. But despite this merger of ownership, a year later both the Leader and the News trailed the Press and the Plain Dealer in circulation. As the old adage goes, desperate times now demanded desperate measures.

According to Plain Dealer accounts, the Circulation War began in the summer of 1913 when Hanna, who had ties to Chicago's newspaper industry through his brother-in-law Joseph Medill McCormick, owner of the Chicago Tribune, imported a number of Chicagoans to Cleveland. These included William P. Leech, formerly an editor of a Chicago newspaper, and two other men, who would later be widely associated with organized crime--Arthur "Mickey" McBride, who founded the Cleveland Browns in 1944 and was a target of the Kefauver Crime Commission hearings here in 1951, and James "The Built" Ragen, who was gunned down in Chicago in 1946 by mobsters who had taken over Al Capone's gang. Leech became Hanna's general manager for both papers and Ragen the Circulation Manager for the Leader, while McBride was assigned the same Circulation position, which entailed building up the paper's circulation numbers, at the News.

Despite his recent arrival in Cleveland, James Ragen wasted no time in going after the Plain Dealer. At his direction, newsboys (also called "newsies"), hawking the Plain Dealer at well-traveled intersections of the city, were threatened or roughed up. Bundles of Plain Dealer papers dropped off at street corners all over the city were torn up or mysteriously ended up in dumps. And, just to show that he was a hands-on manager, Ragen, on November 17, 1913, personally participated in an attack on Joseph Unger, a Plain Dealer newspaper distributor (also called a "circulator") on the east side of town. For his part in that attack, Ragen was convicted in a Cleveland court in January 1914 of assault. Amazingly, he retained his job at the Leader.

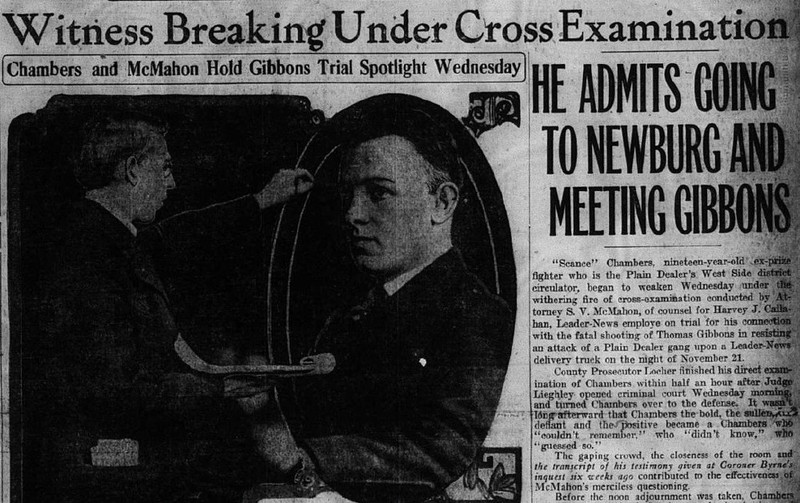

For the next year, attacks against newsboys and their distributors took place all over Cleveland, most of them initiated by employees of the Leader. One of the last occurred on November 17, 1914, when three armed men attacked William "Scance" Chambers, a west side distributor for the Plain Dealer, at the corner of West 117th and Detroit Avenue. Chambers, who some believed was also a member of a west side Irish street gang, didn't take the attack sitting down. According to Cleveland News reports--which though biased carried a certain ring of truth, he and another Plain Dealer distributor assembled a group of "toughs," and on the evening of November 21 transported them to Detroit Center--a cluster of retail stores and saloons on Detroit Avenue near its intersection with West 75th Street and Lake Avenue, to exact some revenge. While most of the hired toughs were having a drink at Louis Schwartz' saloon at 7507 Detroit, Chambers and Thomas Gibbons stood outside watching for the Leader delivery truck. They were standing there when it showed up at around 9 PM. Soon, several shots rang out and Gibbons fell to the ground, bleeding from a bullet wound to the neck. He was rushed to German (Fairview) Hospital, but later died from his injuries.

The killing of Thomas Gibbons--regardless of whether he was an innocent victim, as alleged by the Plain Dealer, or a co-conspirator as alleged in the Cleveland News, galvanized the public to stop Cleveland's Circulation War. Mayor Newton Baker was outraged by the killing and promised that the war between the Leader and the Plain Dealer would soon end. Two Leader employees--Harvey Callahan and Frank O'Neill, were indicted for murder. After a two week jury trial in January 1915, however, which featured dozens of witnesses and wildly differing reports by the competing newspapers, Callahan, was acquitted. The charges against O'Neill, his alleged accomplice, were then dropped. Despite the prosecutor's failure to get a conviction in the case, there were thereafter no reported new incidents of violence between Cleveland Plain Dealer and Leader employees. Perhaps the owners of the two newspapers had sat down over a martini and declared a truce. Clearly at some point they did sit down, because just two years later, in August 1917, Hanna sold the newspaper to the Estate of Liberty Holden, now owner of the Plain Dealer. Publication of the Cleveland Leader abruptly came to an end, also ending more than a half century of competition, as well as at least one war, between these two historic Cleveland newspapers.

Images