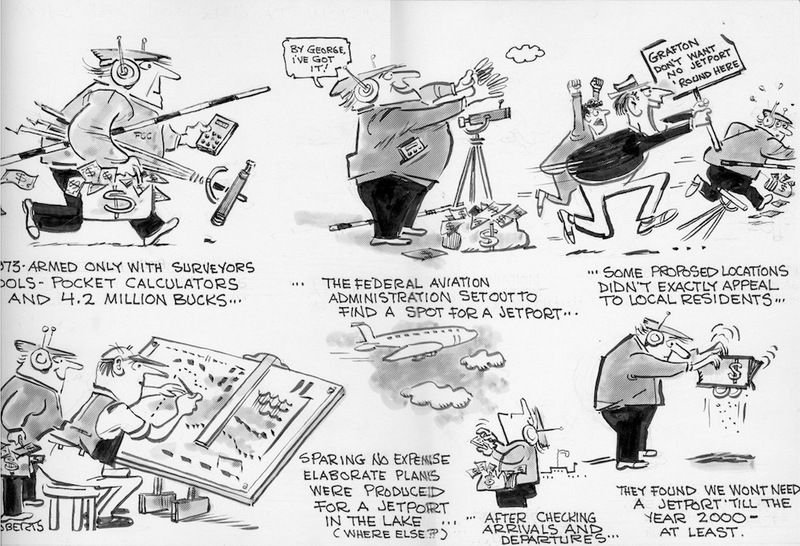

The story of the failed Lake Erie International Jetport is one that generated a flurry of political interest but ultimately succumbed to the grandeur of its own ambition. Mayor Ralph Locher first introduced the idea of a new airport for Cleveland in June 1966. Dr. Abe Silverstein, the director of NASA's Lewis Research Center, revived the idea three years later. Silverstein's comprehensive plan, estimated at $1.185 billion, located the jetport one mile north of downtown Cleveland. The circuitous lifecycle of the jetport-in-the-lake plan represents the midcentury promises that large-scale construction and redevelopment projects offered for metropolitan economic growth. Several such projects swirled around Cleveland in the latter half of the twentieth century, but not all of them reached fruition. For example, Tower City Center was conceived in the 1970s but languished until it was finally opened in 1990.

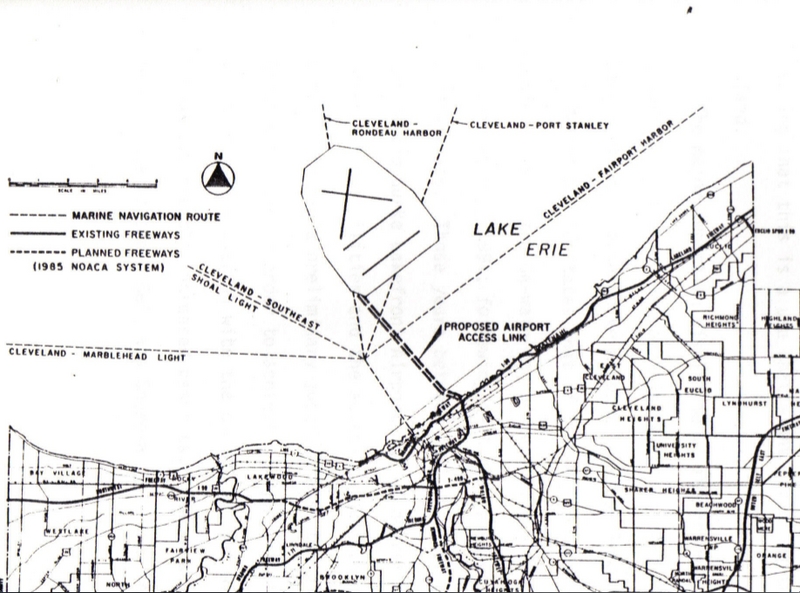

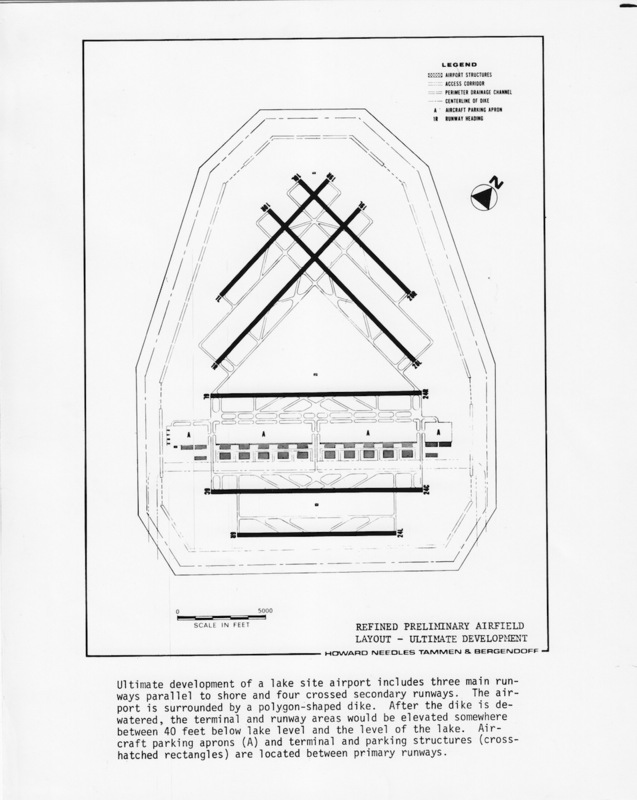

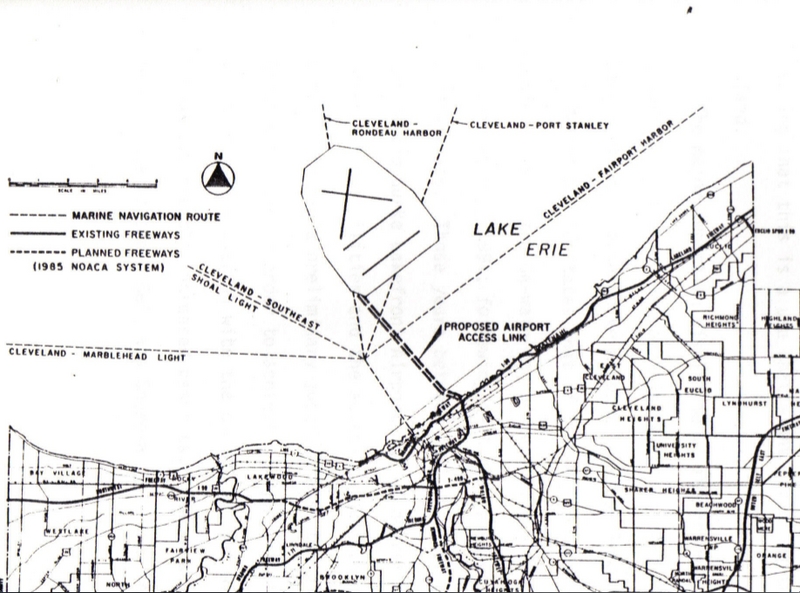

Both Locher's and NASA's plan assumed that by the 1990s Cleveland Hopkins International Airport would be insufficient for the region's commercial air transportation needs. In addition, an offshore jetport would reduce the roar of the supersonic jets that people assumed would become the air travel of the future. In March 1972, Cleveland created the Lake Erie Regional Transportation Authority (LERTA) to facilitate plans for a jetport. Dr. Cameron M. Smith, LERTA's executive director, presided over a board of trustees appointed by the county commissioners and the city of Cleveland. The Federal Aviation Administration underwrote the funding for LERTA's $4.3 million feasibility study in 1972. The study, completed in 1977, recommended building the jetport five miles offshore in Lake Erie on a stone-and-sand dike. The proposed 13-mile dike would surround a manmade landmass, a massive undertaking that would stretch contemporary technology to the limit. The jetport would be accessible by a causeway carrying an RTA rapid transit line and an extension of the Innerbelt Freeway.

Proponents of the jetport cited the additional jobs that would be created by the jetport, positive effects for Cleveland's image and economy, and the practical need for a new airport. However, by the 1970s, the jetport had strong opponents including Mayor Dennis Kucinich. Opponents pointed out reasonable barriers to the construction of the jetport including the project's expense compared to renovating Cleveland Hopkins, weather conditions on the lake, and the failure to explore alternative forms of transportation. The FAA finally predicted that Cleveland would not need a new airport at least until the year 2000 and withdrew support in 1978. LERTA dismissed its employees and the board met only once a year. The Lake Erie International Jetport proved to be a pie-in-the-sky dream that was too expensive and impractical to be built. The promise of improving the infrastructure to serve a growing city's strong economy and prepare Cleveland to leap into the twenty-first century could not overcome admittedly reasonable opposition.

Images