Amateur Baseball at Brookside Park

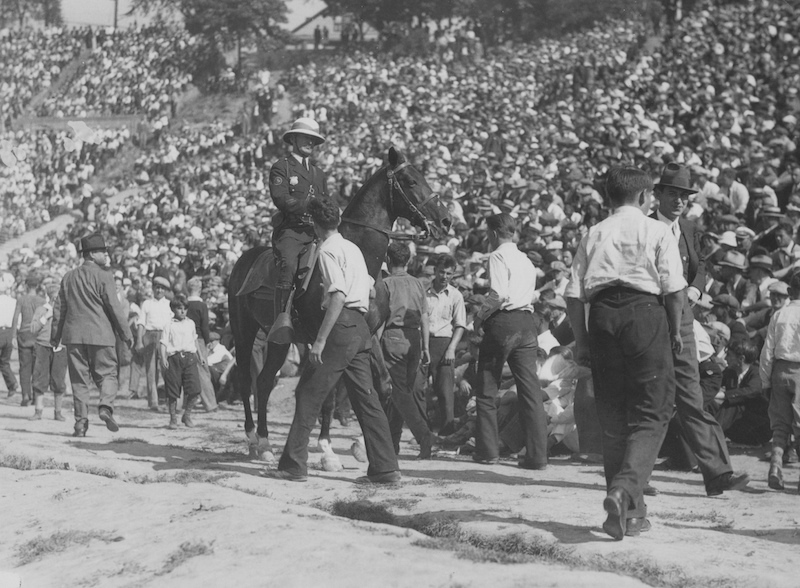

In 1914 and 1915, Brookside Stadium hosted a series of amateur baseball matches that set local and national attendance records. The bowl-shaped natural amphitheater and park setting offered an idyllic atmosphere for the games, which regularly reported audiences of between 30,000 and 80,000. While probably greatly exaggerated, the 1915 Class A intercity championship contest was estimated to have attracted up to 115,000 Cleveland residents. These games would be remembered as the peak of amateur baseball's popularity in Cleveland. But what prompted the throngs of Cleveland residents to line the sloping hillside of Brookside Stadium in what is now the Cleveland Metroparks Brookside Reservation? In part, attendance numbers can be attributed to an aura of public excitement that surrounded the local championship teams; the success of these amateur clubs contrasted with their cellar-dwelling American League counterpart, recently coined the Cleveland Indians. The public enthusiasm, however, should also be attributed to the efforts of the Cleveland Amateur Baseball Association (CABA). The organization developed one of the most successful and influential amateur systems in the nation. CABA helped organize and promote the sport in Cleveland--and amateur baseball's popularity reached unprecedented heights.

Baseball had been a favorite local pastime in Cleveland since before the turn of the century. Amateur games on both private grounds and throughout the park system regularly reported attendance in the thousands; spectators, drawn by both their personal ties to the teams and the option of free entertainment, crowded around the city's numerous official and makeshift baseball diamonds. The teams often represented neighborhoods, churches or places of employment, and were financially backed by these local businesses and institutions. The sport offered players affordable recreation and, to a select few, the possibility of moving on to the professional leagues. While payment of players in upper-level amateur and semi-professional leagues was frowned upon, it was not unusual. The backing of successful teams acted as advertising and offered status to local businesses. In addition, it was not an uncommon practice to charge spectators a small admission fee for games on private grounds. The revenue helped pay both backers and players, or covered the expenses of a visiting team.

By the turn of the 20th century, entrepreneurs had morphed baseball from leisurely recreation into a business. The National League had been establishing itself for nearly 25 years, and the American League was just emerging in markets such as Cleveland. At the professional and semi-professional level, the game was becoming increasingly organized in order to promote and protect the interests of owners and players. As part of this effort to advance the sport, a history of baseball's unique American origins was created by those financially invested in its growth; their marketing complimented the rhetoric of exceptionalism and individualism that was deeply rooted in Progressive Era society. The simple logistics of the highly stylized and complex game, tied in with population growth and urbanization, provided a framework from which the sport emerged as a favorite national pastime. Efforts to organize and market amateur baseball in urban centers such as Cleveland followed, and often mirrored the development of professional leagues.

In February 1910, the Cleveland Amateur Baseball Association was formed. Independent organizations had previously attempted to order and regulate Cleveland's numerous amateur and semi-professional clubs, but had little success competing with the city league. CABA, however, was backed by Cleveland's Department of Recreation as well as the city's moneyed men. Nationally, the organization was the first to successfully integrate its amateur leagues under a single governing body. This was no small feat, as CABA's early efforts included consolidating 18 leagues and nearly 250 teams into an amateur system. While the development of CABA and scope of their local influence was unique, it was informed by the creation of similar amateur organizations throughout the Midwest. In September of the prior year, for example, a branch of the National Amateur Baseball Association was formed in Cincinnati. This organization's development was governed by regulations from the National Amateur Baseball Association of Chicago, which was established as a union in 1906 by semi-professional baseball players of Chicago. Just as in Cleveland, these associations were meant to govern and standardize the sport between leagues and cities.

CABA was founded on the premise of promoting and protecting amateur baseball, which was growing in popularity each year. The role of the organization was predominately administrative; park officials were dealing with more independent teams than ever before. CABA, with the support of the city, was to provide assistance in the development of new grounds, improve preexisting fields, administer their use, and act as the point of contact for setting up games between teams- the latter of which was previously achieved by clubs advertising in newspapers. An umpire's association was also formed; CABA administrated both the assigning of games to officials and compensating them for their work. To pay the costs of this work, CABA annually held a field meet known as "Amateur Day." Proceeds from admission were used to cover the organization's yearly costs.

From 1910 to 1914, CABA's efforts focused on creating a competitive environment to generate public interest in the amateur system. The organization drafted rules and standardized the city's various leagues. Membership to the amateur system was free, with each player being required to sign a contract. American League rules of play were adopted, and teams were placed in four divisions--A through D--based on the age of the participants. Within each divisions, teams would battle to claim the title of city champion. Fostering the creation of a competitive environment paid off quickly; the 1910 Class A championship game at Brookside Stadium drew an estimated 30,000 spectators.

To ensure the stability of the amateur system, the power of managers was greatly expanded under CABA's administration. Rules and regulations were implemented to promote the support of financial backers. Newly drafted laws prevented players from jumping teams without written permission from a manager. This assured backers that the team in which they invested would retain its star players and, in a worst case scenario, that they would not be forced to disband their team if multiple members were given a better offer from a competing backer.

Other laws were drafted in a futile effort to remove what was deemed to be "professionalism" in the amateur sport. The organization threatened to expel players who demanded cash and throw out teams paying their players. After learning that nearly all Class A and many Class B players were being compensated, attempts were briefly made in 1912 to incorporate a semi-professional Class AA division that allowed for this practice. As it became clear that backers meant to enclose baseball diamonds and charge admission to the semiprofessional games, the league was quickly disbanded. By 1913, CABA had declared its intentions to wipe out the practice of paying players and worked to secure evidence against known offenders. As baseball was being marketed as a unique American institution, engrained with the simplicity and morality of the country's rural past, CABA rules were meant both to reinforce these ideals and minimize what was perceived to be the corrupting influence of commercialism on the sport. Charged by the rhetoric of the Progressive movement, city officials and social organizations supported the efforts of CABA as a means to promote the physical development of youth and provide sober recreation to the city's growing populace.

Within only a few years, CABA created an amateur system that attracted a high level of public attention. Their program earned a reputation as having the largest and best amateur baseball card available to the city's residents. By 1913, CABA made its first attempt at promoting intercity championship games. Working with leagues from St. Louis and Chicago, a tournament was scheduled. Problems quickly arose: there was a general lack of continuity in the rules and schedules employed by the multiple leagues. It was apparent that a governing body was needed. This set the stage for the sport's boom in popularity.

In February 1914, representatives of CABA met with members of thirteen other amateur leagues in Chicago to organize the National Amateur Baseball Association (NABA). The object of the meeting was to develop an elimination series for determining a national amateur baseball champion. With over 200 teams expected to participate, NABA split the fourteen cities into four sections, each representing four cities. Each city would organize its own league, with membership limited to unpaid players. The winner of the city championship would move on to a sectional intercity tournament, with a national title to be held about the same time as the major league championship game.

Cleveland's elimination series proved incredibly successful in raising public interest in the amateur sport. The 1914 Class A city and intercity championship games drew record-setting numbers of spectators to Brookside Park. Tournament games were reported to have attracted between 25,000 and 80,000 persons, with high attendance dependent on the cooperation of weather. Cleveland's Telling Strollers pushed through the city and sectional rounds, and moved on to beat Chicago's Butler Bros in a three game series for the Amateur World Series. The 1915 series proved even more successful in drawing the public to Brookside Stadium, with the Cleveland White Autos securing the national championship.

NABA's success, however, would prove to be short lived. Conflict within its governing body resulted in a schism at a 1916 meeting. The often tenuous relationship between local politics and businesses--not unusual in either professional or amateur baseball--had reached a breaking point within the organization and needed renegotiating. Led by the future mayor of Cleveland, Clayton Townes, representatives from ten of the fourteen cities composing NABA formed the National Baseball Federation. The Federation was created for the same ends as NABA, but with two distinctions. Concerned over the growing influence of sporting goods dealers in NABA's governing body, NBF's membership was restricted to non-commercialized baseball associations. The new federation also developed a AA semi-professional league as a response to amateur teams employing semi-professionals for tournament games. NBF would allow the payment of players in this new league, as long as baseball was not the main source of their income. With the Federation's leadership closely tied and influenced by Cleveland amateur baseball, CABA allied itself with the NBF.

Even with internal divisions and the advent of the Great War, amateur baseball continued to attract large audiences in Cleveland. Cleveland teams dominated NBF's Class A division in 1916 and 1918, and tied for the 1917 championship. NABA and CABA officials suspended their work for the duration of the war in 1918, probably in response to many players' responsibilities at factories and docks under the "Work or Fight" order from the War Department. The NBF focused its efforts on fundraising projects for American troops. Prior to the 1919 amateur season, however, it was decided that a merger between NBF and NABA was in the best interest of the amateur sport. The namesake of the the National Baseball Federation was kept.

CABA remained at the forefront of amateur baseball in Cleveland until 1932. While both CABA's development as an independent body and the control that they were able to assert over the amateur system was key to their growth, it eventually resulted in the organization's downfall. With the election of a new mayor in 1931, the commissioner of Cleveland's recreation department was forced to resign; this official was also the acting secretary of CABA. The ousting was primarily due to a shift in administration and Depression induced budget cuts. The commissioner's resignation, however, was accompanied by allegations that CABA had received preferential treatment from the city in the assignment of playing fields. CABA responded to the new administration's actions by removing their office from City Hall --symbolically breaking its longstanding relationship with the local government. The Cleveland Baseball Federation was quickly formed to take its place. With strong ties to the local government, backers of many major teams aligned with the Federation. CABA's governing body suspended its activities on April 21, 1932, citing concerns over securing adequate fields from the new administration and a decrease in backers' willingness to invest in the unstable economic climate. For twenty-one years, the organization had managed the development of sandlot baseball in Cleveland. The organization earned a reputation nationwide for its success in promoting and advancing the sport, and was a model for its organizational structure. Building upon the work of CABA, the Cleveland Baseball Federation continued to grow and refine the city's amateur system into the 1950s. For the better part of a half-century, Cleveland was home to the strongest and most popular amateur baseball systems in the country.

Images