Alan Freed and the Moondog Coronation Ball are virtually synonymous with the breakthrough of rock & roll. Freed didn’t invent the term or the genre; but like no previous celebrity, he gave it a voice. And the Moondog Coronation Ball was far from rock & roll’s shining hour; but it ushered in a new era for live music. Together, the man and the event became the faces of a new medium, a revolutionary form of entertainment, and an ever-expanding musical lexicon. Their intertwined and flawed (but increasingly varnished) legacies endure to this day.

Already a seasoned radio disc jockey in Youngstown and Akron, Alan Freed had his first Cleveland gig in 1949 as an afternoon movie show host on WXEL-TV. In 1951 he was hired to host a classical music program on WJW-Radio. However, Freed’s direction soon changed when popular record-store owner Leo Mintz volunteered to sponsor a three-hour, late-night radio show with Freed spinning rhythm-and-blues records by Black musicians. Much like Sam Phillips at Sun Records, Mintz had recognized the burgeoning appeal of Black (“race”) music to young White consumers. Freed grabbed the opportunity and his new show, the Moondog Rock & Roll House Party, was a near-overnight success. As one of a small handful of White disc jockeys pushing rhythm and blues, Freed became an industry force, a true influencer with the power to make or break records with his airplay. The self-anointed Moondog was a “hit man.” And rock & roll was here to stay.

The two terms—rock & roll and moondog—are an etymological story unto themselves. Historians generally describe rock & roll as the confluence of traditionally Black musical styles, such as blues, jazz, and gospel, or as an evolving hybrid of rhythm & blues (R&B), pop, and country music. Throughout the 1950s, the terms rock & roll and R&B were often used interchangeably. However, the term rock & roll predates Freed by about 70 years. In 1881, comedian John W. Morton of Morton's Minstrels performed a song titled "Rock and Roll." Five years later, a comic song titled "Rock and Roll Me" was performed by the Moore's Troubadours. Still, these tunes did not refer to a musical form but, most likely, to swaying dance movements or (some believe) to the rocking and rolling movement of watercraft. These connotations held well into the 1930s, with rock & roll references adopted by performers such as the Boswell Sisters and Verne and Irene Castle. Around that time, however, many of the era’s popular blues singers recast rock & roll in significantly more explicit terms. Some of the starkest examples might be 1944’s "Rock Me Mama" by Arthur Crudup (“Rock me mama like a southbound train”) or 1951’s "Sixty Minute Man" by Billy Ward and his Dominoes ("I rock 'em, roll 'em all night long"). From that point forward, rock & roll—the music and the motion—became the disruptive and often sexualized experience that we know today.

Moondog (or moon dog), on the other hand, is a meteorological synonym for “paraselene (par-uh-si-lee-nee)”: faint glimmers caused by moonlight refracted through ice crystals in certain types of clouds. But this was not the inspiration for Freed's nickname. In 1949 an eccentric musician and composer named Louis Thomas Hardin Jr. christened himself Moondog (in honor of a pet that constantly howled at the moon) and composed a classical piece eponymously called "Moondog’s Symphony." Keen to hippify his image, Freed co-opted the name, thus paving the way for his Moondog Rock & Roll House Party radio show and 1952’s Moondog Coronation Ball. In 1954, Hardin sued Freed and won. Freed was ordered to apologize and cease using the name Moondog on the air. However, the term had already become enmeshed in American culture—the eventual subject of multiple rock songs, musical events, cafés, and even basketball-team mascots. One of the names initially considered by the Beatles was Johnny and the Moondogs.

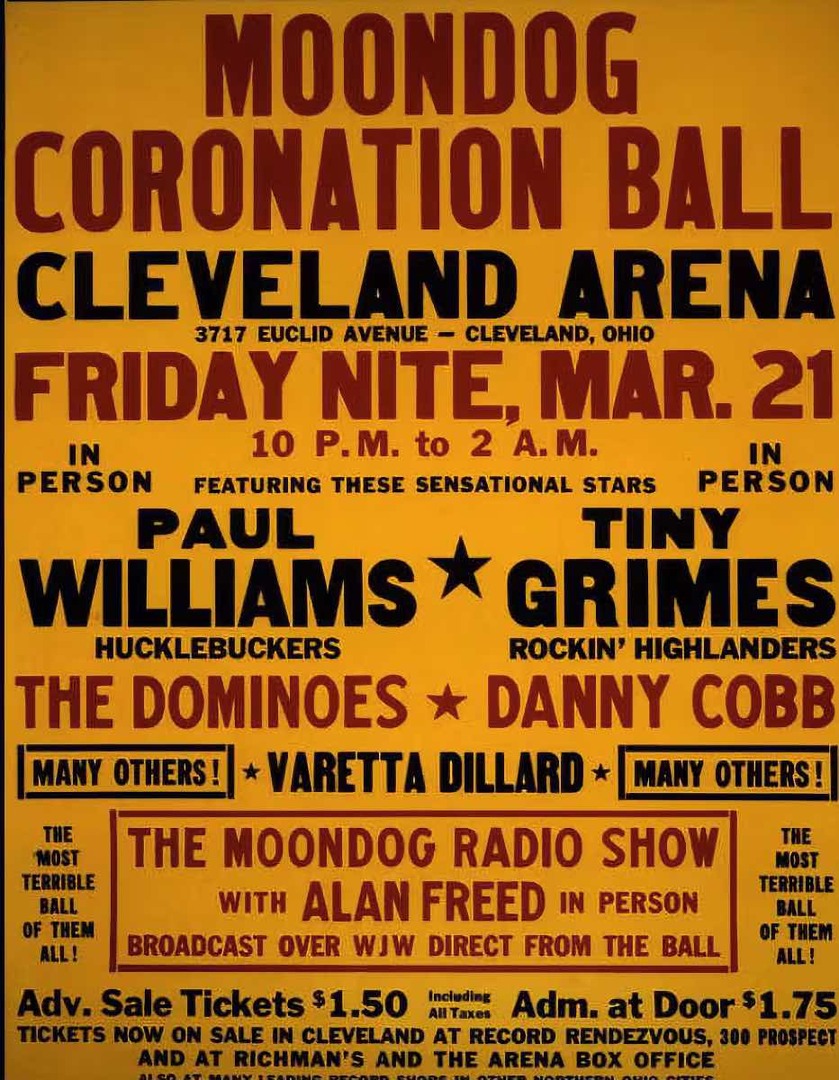

The 1954 lawsuit was not Moondog Freed’s first humbling moment. That would be the seminal but scandal-plagued stumblefest he called the Moondog Coronation Ball. “Coronation” referred to an intermission event during which the most popular male and female teen would be crowned. Organized by Freed, Mintz, and concert promoter Lew Platt, what is now dubbed America’s first rock concert was set for March 21, 1952, at the Cleveland Arena on Euclid Avenue. The bash would include saxophonist Paul Williams and his Hucklebuckers, Tiny Grimes and the Rocking Highlanders (an African American instrumental group whose members wore kilts), the Dominoes (one of the early ’50s’ most successful rhythm and blues bands), teenage R&B singer Varetta Dillard, and jazz/blues-man Danny Cobb. According to former Rock & Roll Hall of Fame president Terry Stuart, “when Freed opened the show, the [overwhelmingly Black] audience could not believe the exuberant radio personality whose show they had been listening to for months was white. The delighted crowd went nuts."

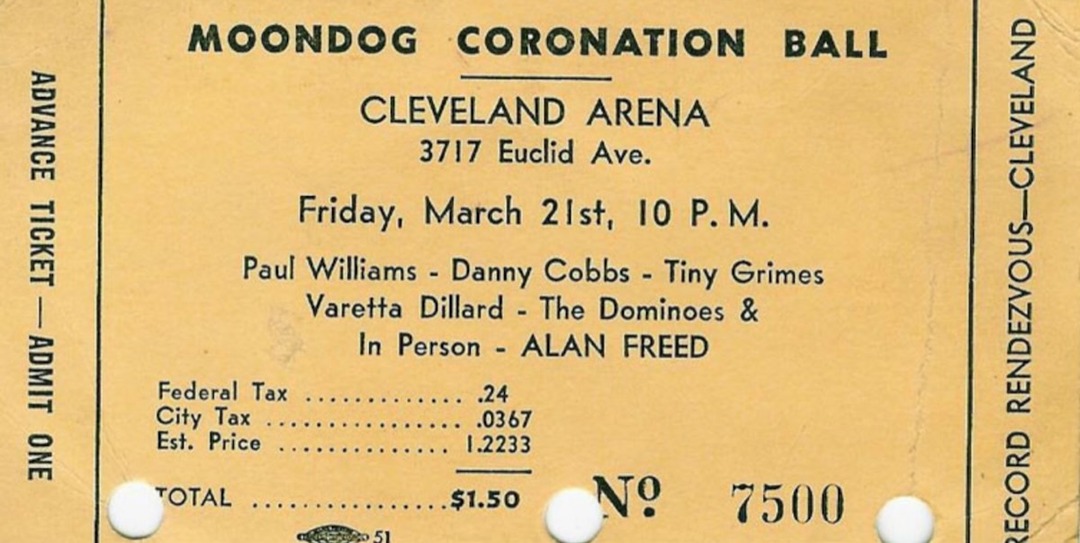

The show’s downfall was a simple printing error: Tickets for a later Moondog event had been printed without a date, thus giving additional thousands access to the March 25 event. A number of tickets also were counterfeited. Ultimately, about 20,000 to 25,000 showed up, with the ticketed and ticketless stuffing the Arena far beyond its 9,500-seat capacity. Hundreds had forced their way in, broken down doors, smashed glass, and pushed past police. Accounts vary as to how long the 10:00 PM concert lasted: somewhere between 15 minutes and two hours. It also isn’t clear which authorities, police or fire, ultimately called a halt. Either way, the crowd was ordered to leave well before the midnight coronation. Most did so reluctantly. A few were more belligerent (one person reportedly was stabbed). The country’s first rock & roll concert—which one promotional poster had presciently called "the most terrible ball of them all"—was kaput.

Blowback was swift and brutal. Fire Department officials prepared charges (ultimately dropped) against Freed and his two associates. The Cleveland Press reported “a crushing mob of 25,000.” The Plain Dealer stuck closely to the facts, but the Call & Post hit Freed with both barrels, calling him unscrupulous and “the fast-talking, wisecracking Pied Piper of the airwaves.” The paper further accused Freed’s radio show of attracting “the most vicious and most depraved elements of society.” The next day, with his job on the line, Freed took to the air, apologizing effusively while claiming that he was not the promotor but rather a “hired hand.” Days later, the Call & Post fired back, citing evidence that Freed assuredly was a co-promoter. Two months after the concert a real moon dog was spotted in the sky over Cleveland (In folklore, moondogs are harbingers of stormy weather.).

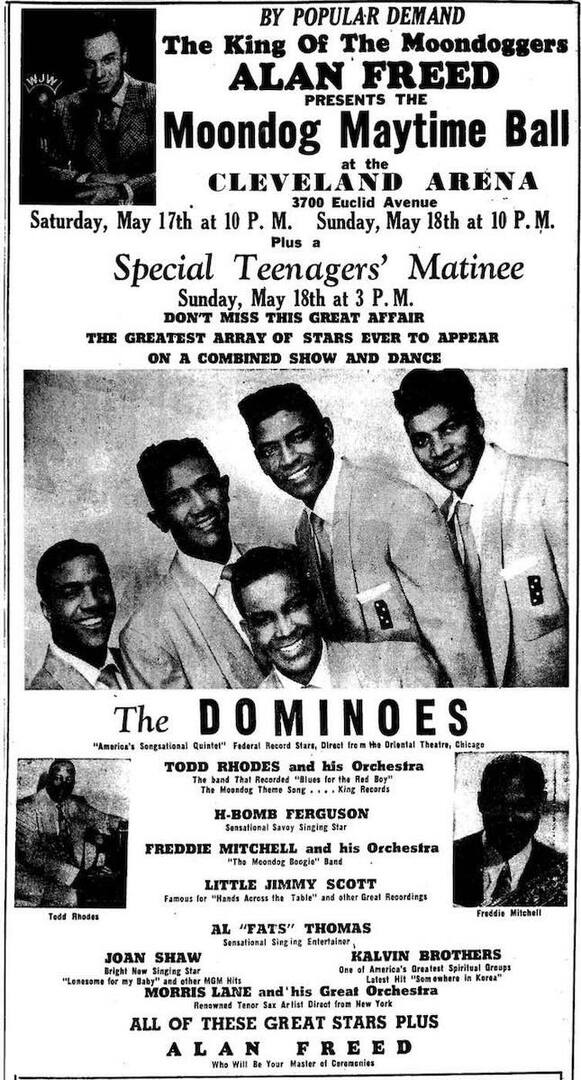

Still, Freed won the PR battle, kept his job, and was quickly back in action. Another Moondog show—this time at Public Hall and featuring Dinah Washington, Woody Herman, and the Mills Brothers—came off with no problems on May 25, 1952. In July 1953, Freed returned to the Arena to host the Joe Lewis Show, an R&B event featuring the former heavyweight champion. A Plain Dealer reporter’s distressingly bigoted review of the concert referred to the audience as “trained squeals” and the evening’s “race music,” as recordings that “sell by the hundreds of thousands in shops South of Euclid Ave.”

Later that same year Freed caught what may have been his biggest break. WJNR began daily rebroadcasts of Freed’s shows to listeners in New York and New Jersey. Additional markets soon opened up, including the Armed Forces Network in Europe. By 1954 Freed had moved to WINS-AM in New York City, launching what might be considered his golden age. Over three years he expanded his radio empire, established his own record label (End Records), and produced (and appeared in) several cheesy rock & roll movies. So vast was his reach that J. Edgar Hoover's FBI put Freed under surveillance. As broadcast historian Mike Olszewski recalled, “Back then, it seemed, the United States was always looking for new enemies.”

Comprising equal parts PR and paranoia, Hoover’s actions reflected a nation of two minds. One side recognized a musical future of increased tolerance and innovation. The other saw an assault on long-held “traditional values.” In 1957, Freed’s rock & roll show on ABC television was cancelled after black R&B singer Frankie Lymon danced with a white girl on stage at a Freed-promoted concert. The next year, Freed lost his job at WINS radio after he supposedly yelled “The police don’t want you to have fun,” at an event in Boston. Although he quickly resurfaced on rival radio station WABC-AM, the beginning of the end wasn’t far off: On November 21, 1959, Freed was sacked after declining to sign an FCC document stating that he never received funds or gifts for playing records on the air. Although he was only fined, the implied admission effectively ended his broadcasting career and his high profile made him a poster child for the practice of payola. Payola is generally thought of as a “pay-to-play” arrangement between promoters and DJs. However, the then-common practice often involved more complex relationships, such as fake songwriting credits, royalty kickbacks, and hidden ownership of recording interests. Freed, for example, was wrongly given partial songwriting credit (and royalties) for Chuck Berry’s "Maybellene" and The Moonglows’ "Sincerely." Rock critic Nadine Cohodas once described Freed’s relation with the owners of Chess Records as “a warm friendship shaped by money.”

In 1960 payola was formally classified as a crime and two years later Freed was convicted of commercial bribery. Once again, he escaped with only a fine. The same activities got him indicted (but apparently not convicted) of tax fraud in 1964. By this time he had moved to Florida and was working only sporadically at Miami-area radio stations. Freed died January 1965 at the age of 43 and is buried in Cleveland’s Lake View Cemetery.

Since his death, Freed’s legacy has grown in mostly positive ways. Historically speaking, he may still be the face of payola. But his reputation as patron saint of rock & roll has largely pushed payola to the sidelines. Rock is now considered the musical font from which most popular music has emerged—from do-wop, soul, and psychedelic to punk, grunge, and pop. Moreover, the Moondog Coronation Ball is deemed the foundation stone upon which every live-rock event is built, and as DJ Norm N. Nite once stated, “If it wasn’t for Alan Freed and the Moondog Coronation Ball, Cleveland would not have the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.”

Perhaps most important, Freed can legitimately be seen as an early crusader in the battle for racial equality. Opportunist though he was, Freed worked tirelessly to promote Black performers, reach mixed audiences, and stage events where racial integration was accepted and encouraged. More than most other media, “his” music transcends social classes, age groups, and race.

Images