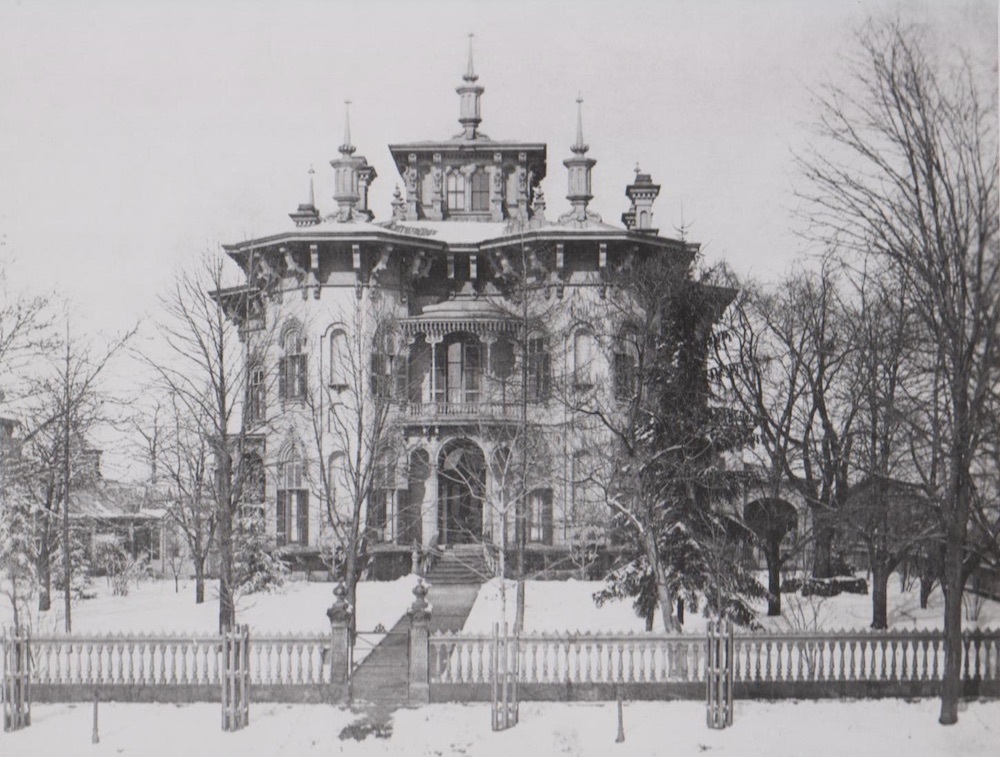

Euclid Avenue's "Millionaires' Row" was home to some of the nation's most powerful and influential industrialists, including John D. Rockefeller. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Baedeker's Travel Guide dubbed Euclid Avenue the "Showplace of America" for its beautiful elm-lined sidewalks and ornate mansions situated amid lavish gardens. The concentration of wealth was unparalleled, with accounts at the time comparing it to the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris.

Rufus Dunham was the first to invest in the stretch of Euclid Avenue, purchasing 140 acres of land to open a farm and tavern to service stagecoaches passing through Cleveland. Dunham faced problems, however, as the city did little maintenance and the road would often flood. As other wealthy elites began moving into the area, the city developed a drainage system to prevent flooding and made the area more desirable.

The residents of Millionaires’ Row did not just build homes in Cleveland, but often donated money to charitable organizations and funded the construction of other establishments. Some of these investments went toward the construction of churches, universities, medical schools, the art museum, orchestra, and the historical society. The best-known Euclid Avenue resident was John D. Rockefeller, who started Standard Oil Company. Other notable businessmen who called Euclid Avenue home were Amasa Stone, Marcus Hanna, and Samuel Mather.

In 1910, Cleveland was the sixth largest city in the country. With the increase in population and new developments encroaching, Euclid Avenue experienced a drastic rise in taxes and land costs. These rises were just the first step in the downfall of Millionaires’ Row.

Millionaires' Row gradually shifted eastward as commercialization claimed some of the older homes near downtown. By the 1920s, a suburban exodus to "the Heights" east of the city illustrated that the very prosperity created by the denizens of Euclid Avenue ultimately displaced their grand homes. A number of the luxurious homes were demolished in the 1920s and 1930s to make way for commercial buildings and parking lots. In the 1950s, more homes were destroyed to make way for the Innerbelt Freeway. Today, only a handful of homes still exist, giving us just a glimpse of the splendor that once was considered the wealthiest address in the nation.

Audio

Images