In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the museum movement was sweeping the United States. Some cities had long-established art museums while others looked to form new ones. Cities without permanent exhibition spaces welcomed traveling exhibits for short periods of time. Cleveland was one of these cities that lacked a permanent art museum, so it hosted traveling exhibitions at Central High School. A spate of influential art museum openings in the 1880s helped ignite local interest in securing a museum for Cleveland. In 1880 President Rutherford B. Hayes dedicated the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. With Cincinnati and Detroit founding art museums in 1881 and 1885, respectively, Clevelanders wanted a museum of their own. Some Cleveland artists were showing their work in the Met and made sure to note that they were unable to show their work in Cleveland due to the lack of a museum.

The first opportunity for a Cleveland art museum came with the death of Hinman Hurlburt. With the probating of his will in 1884 came the announcement that the majority of his estate and art collection should be put toward an art gallery. However, the part of his estate set for a museum would have to wait until his wife passed. The question, “Who will found for us a museum of art?” was posed at the Annual Patron Banquet for the Art School in 1888. This open call for creation of a museum in Cleveland continued to circulate and build momentum. These calls also brought whispers of potential donors. John Huntington contemplated creating a museum with the proposal of donating his personal art collection to Cleveland in 1889. The Art School also began to discuss plans for a combined museum and college. When Horace Kelley died late in the following year, he left most of his $500,000 estate for an art museum.

Two more years passed before the next big advance in museum plans. On December 25, 1892, Jeptha H. Wade II gifted a plot of land in Wade Park to the Kelley Art Trustees for the museum. The location in Wade Park was a little larger than four acres and sought after by Western Reserve University, the School of Art, and the Cleveland Park Commission. Wade originally expected the Kelley Art Trustees to pay for the parcel but chose to gift the land with newspaper announcements being made on Christmas Day. The acquisition of the land and the money from the Horace Kelley Trust led to increased pressure from Clevelanders asking for a museum to be built. Even with the land for the museum secured, seven more years passed before the Horace Kelley Trust set up a corporation for the museum.

Henry Clay Ranney was one of the trustees for both the Hurlburt and Kelley trusts, but he was also one of the executors of John Huntington’s estate. Huntington’s wishes for a museum were rumors until his death in 1893, when his will was released setting up a trust for a gallery and museum. Ranney, now trustee of all three estates, worked to unite all three to make one museum because he saw that they all had similar wishes. On March 16, 1899, Ranney sent off articles of incorporation to formally establish the Cleveland Museum of Art. He was elected as the first President of the museum that May. The newly formed Board of Trustees was composed of many notable men including J. H. Wade, George H. Worthington, Samuel Mather, William B. Sanders, Samuel Williamson, and Liberty Holden. John D. Rockefeller and Charles F. Brush were also elected but decided not to serve due to other engagements.

Despite the pressure to build immediately, preliminary steps toward the creation of the museum were being taken slowly. Another seven years passed before the architects Hubbell and Benes were chosen for the project in 1906. Preliminary plans were set in motion after the selection of the architects. In April 1907, a six-person committee discussed the first plans but called for revisions. The committee included Ranney, J. M. Jones, J. H. Wade, William Sanders, Liberty Holden, and Hermon Kelley. The committee traveled to Boston to talk to Edmund Wheelwright, the consulting architect for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and trekked across Europe taking notes, and its members continued to discuss and revise plans for another six years before building began.

During planning, battles erupted with the city over location disputes. The Museum Committee wanted to orient the museum east-west which would change the boundary of the land gifted by Wade, an action requiring city approval. The city rejected this proposal due to the cost to the city, but ultimately approved a new proposal in December 1908 with the building facing University Circle and Wade Lagoon to the south. The Committee and the city, particularly Mayor Tom Johnson, also disagreed on payment which was tied to when the museum would be open to the public. The Huntington will stipulated that the museum would offer admission-free days, but Mayor Johnson was trying to force the hand of when the free days would occur. The dispute ended with the conclusion of Johnson's five-term run in January 1910. Herman Baehr came into power and helped settle the dispute. Behind closed doors the Kelley Trust received a quitclaim deed from Wade to secure museum expansion in 20 to 30 years. More bad news came in March of that year. The Museum discovered that only $75,000 would come from the Hurlbut gift, not the original estimate of $500,000 that they had planned. The shortfall was resolved when the Huntington Trust agreed to pay two-thirds and the Kelley Trust one-third toward the cost of building, finally permitting the first steps to commence on building the museum.

The headline “First Stake Driven for Art Museum” introduced surveying action that occurred on the property in 1911 and Hubbell’s promise that the building would be completed in two years. Despite his claim of such a short build time, more challenges appeared. Even with the Huntington and Kelley Trusts taking on the cost, they were over their $1 million budget. The original plans centered around the three trusts were now questioned. The design committee went over a variety of new plans presented by Hubbell including new one-story options to help save money. Ultimately, they chose to go with a two-story option that gives the look of a single story from the north but presents a grander facade when viewed from across Wade Lagoon to the south. The design, rendered in white Georgian marble, reflected the Beaux-Arts influence that accompanied the pervasive City Beautiful movement of the time. In the fall of 1912, with little progress made, the Trustees blamed the architects for the delay of the museum. In the meantime, roads around the planned museum location were being constructed and by 1913 excavation was under way to move the Perry Monument from its spot in Wade Park to Gordon Park to make room for the museum. Excavation continued without pause until 1914 when police stopped construction due to missing permits. Along with missing permits, the plans for the building violated state building codes and Hubbell had to adjust the plans again to add more exits and reach code approval. After obtaining the proper permits, construction continued.

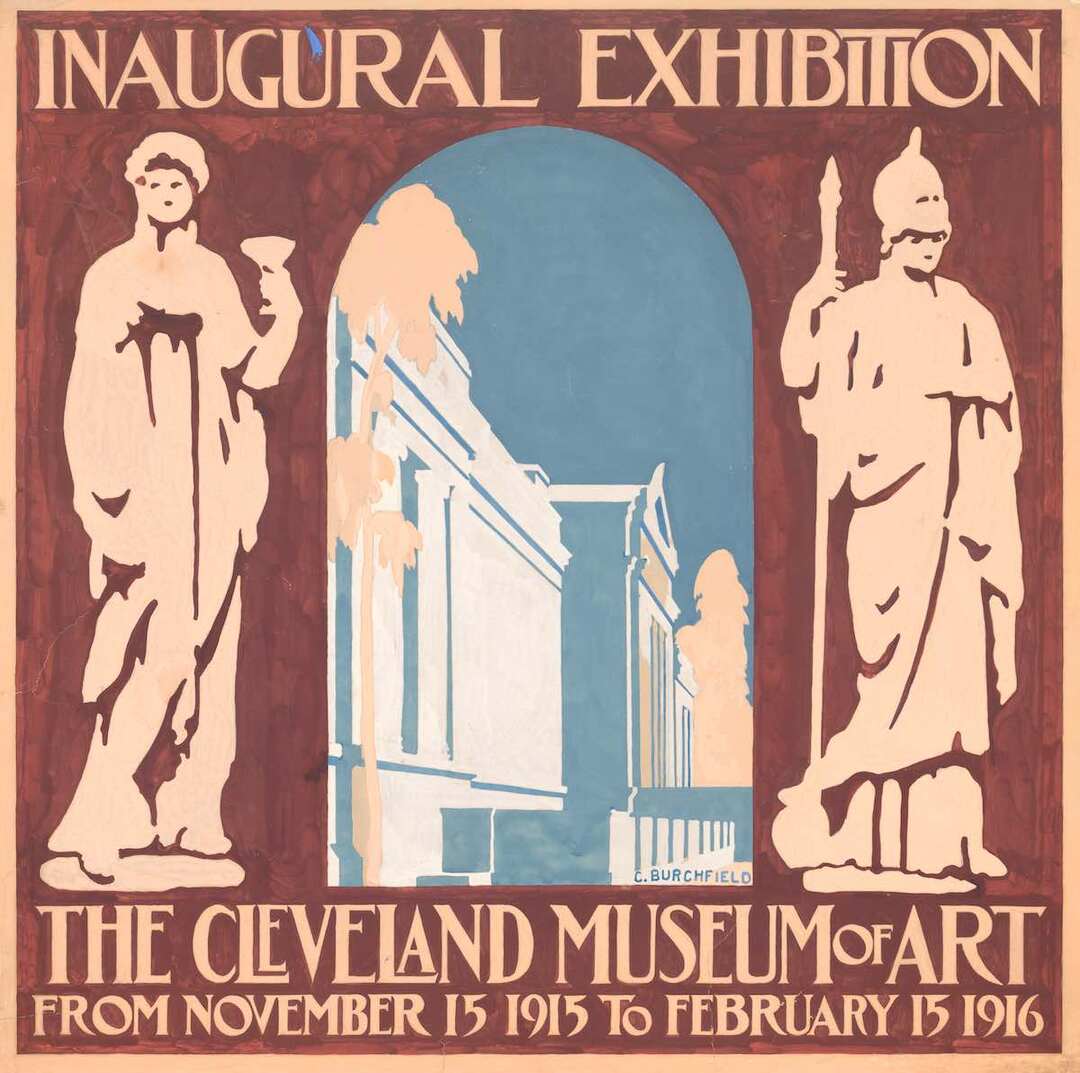

The museum committee announced the hiring of J. Arthur MacLean from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts to be the curator for the museum on September 6, 1914. Through the final phases of construction, the museum committee had calls for donations and searches for collections, but on June 7, 1916, it finally opened to the public. The accounts of opening night detailed it as marvelous and well attended. According to one, “the event marked the culmination of the dream and plans of thousands of Clevelanders to have a Cleveland art museum which would stand as a civic asset.” The museum was officially turned over to the people by the president of the museum association Judge William B. Sanders, who paid tribute to the founding donors John Huntington, Horace Kelley, and Jeptha Wade as well as the architects. The opening also welcomed new announcements for collection donations to help fill the museum’s galleries.

In addition to being known for its extraordinary collections, perhaps the Cleveland Museum of Art’s most singular attribute was its free days. From the start, the museum was open two days a week to the public at no charge. Not only was admission free but the museum was focused on education and provided free spaces for students to draw. This set the museum apart from art institutions in other cities. In keeping with its founding principles, the Cleveland Museum of Art later expanded this legacy, and its permanent collection is now always free to the public.

Images