Cook-Bousfield Mansion

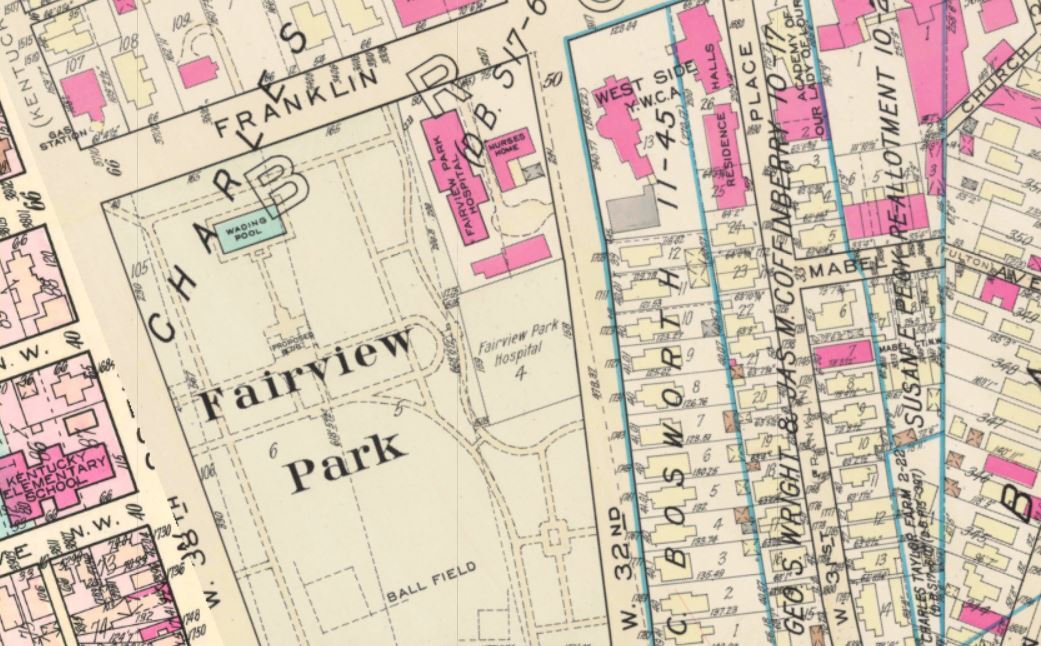

The Cook-Bousfield mansion sits at the corner of Franklin Boulevard and West 32nd, formerly known as Duane Street. Famously dubbed the west side’s “Millionaires' Row,” Franklin was home to elite businessmen and influential politicians. The Cook-Bousfield mansion sits only a few hundred yards from Franklin Circle, the newly rehabbed Rhodes mansion, and the Spitzer-Dempsey mansion.

The Cook-Bousfield mansion at 3105 Franklin Boulevard was originally built in 1853 for businessman Hiram Cook. It was constructed in the popular Italianate style. Not much is known about Hiram Cook, other than that he was a wealthy lumber dealer in the area. Cook sold the residence early on, and notable Cleveland residents John and Sarah Bousfield (née Featherstone) moved into the home in 1863. John Bousfield owned Cleveland Wooden Ware Manufacturing Company with his business partner J. B. Hervey. The business eventually collapsed and led to the Bousfield's temporarily leaving the company of Franklin’s finest. It is likely that the Bousfields were responsible for the substantial style change to the mansion around 1869. No longer strictly Italianate, the mansion boasted a mansard roof that covered the original belvedere. The mansard roof remains today, essentially blending the Italianate style with Second-Empire influence.

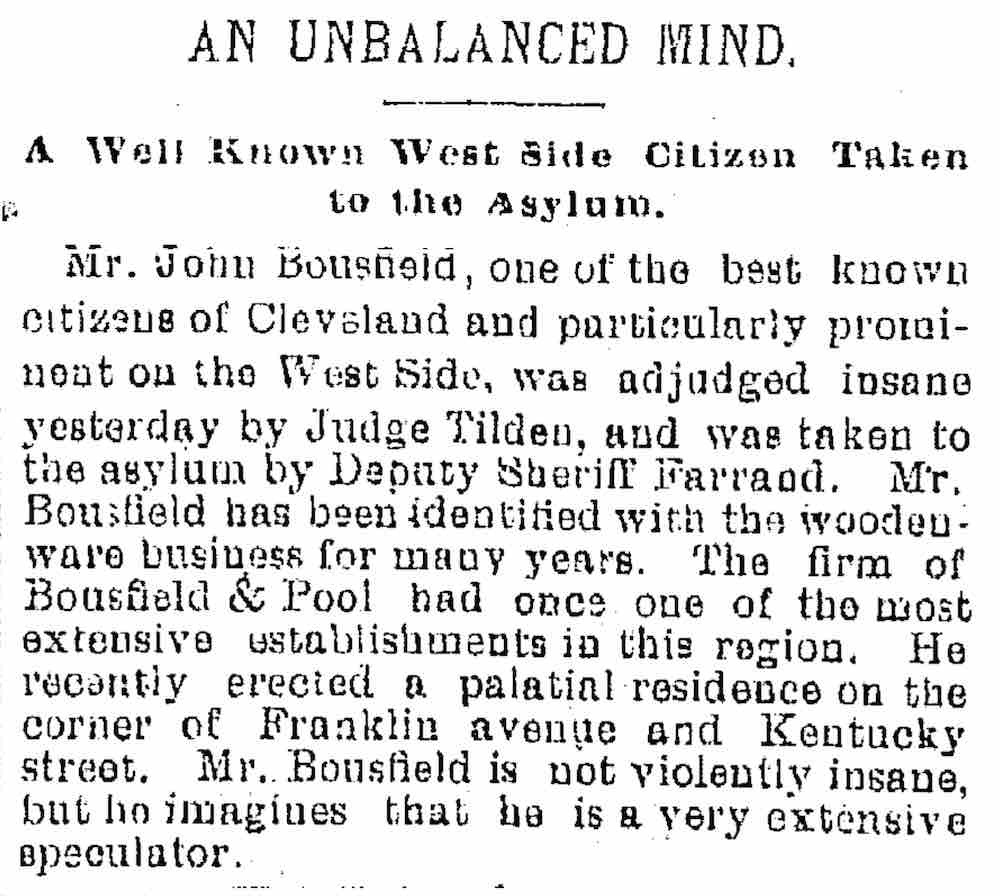

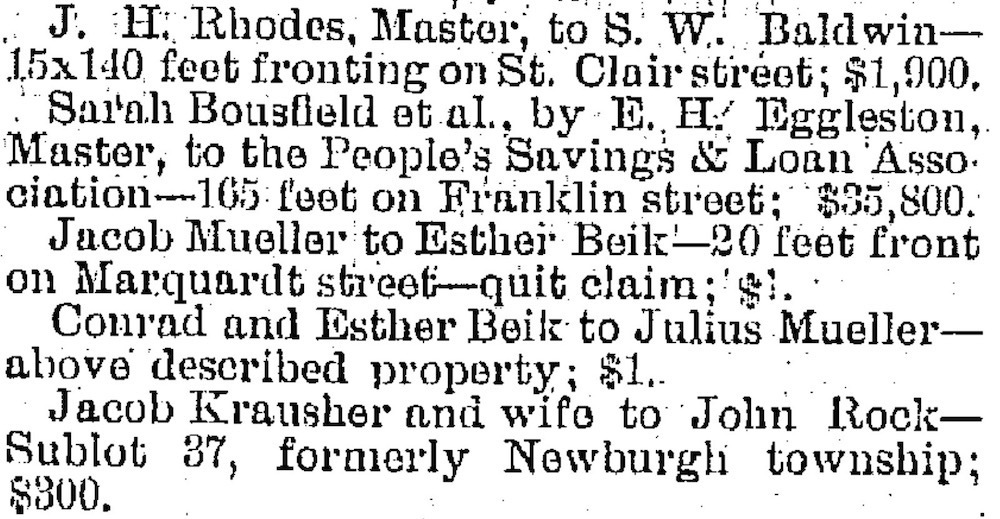

When Bousfield’s woodenware business went under in 1875, he lost everything, including his home. The bank did not actually foreclose on the home until around 1880, but the Bousfields were already plotting their return to Franklin. Because of his social status, John Bousfield was involved with his neighbor’s businesses and had good relationships with Cleveland’s west side elite. Along with prominent names like Coffinberry and Rhodes, he was involved in founding People’s Gas Light Company, of which he later became President. He was also Vice President of the People’s Savings & Loan Association, which later foreclosed his 3105 Franklin home. Luckily, these positions earned him enough money to build a new mansion on the corner of Franklin and West 38th Street, just northeast of his old one. Known as Stone Gables, this new home would be even more grandiose, with seventeen rooms just for the Bousfields. The couple rented out the remaining half of the house, supplementing their income. Stone Gables still stands as a private residence and inn, and it has been painstakingly restored.

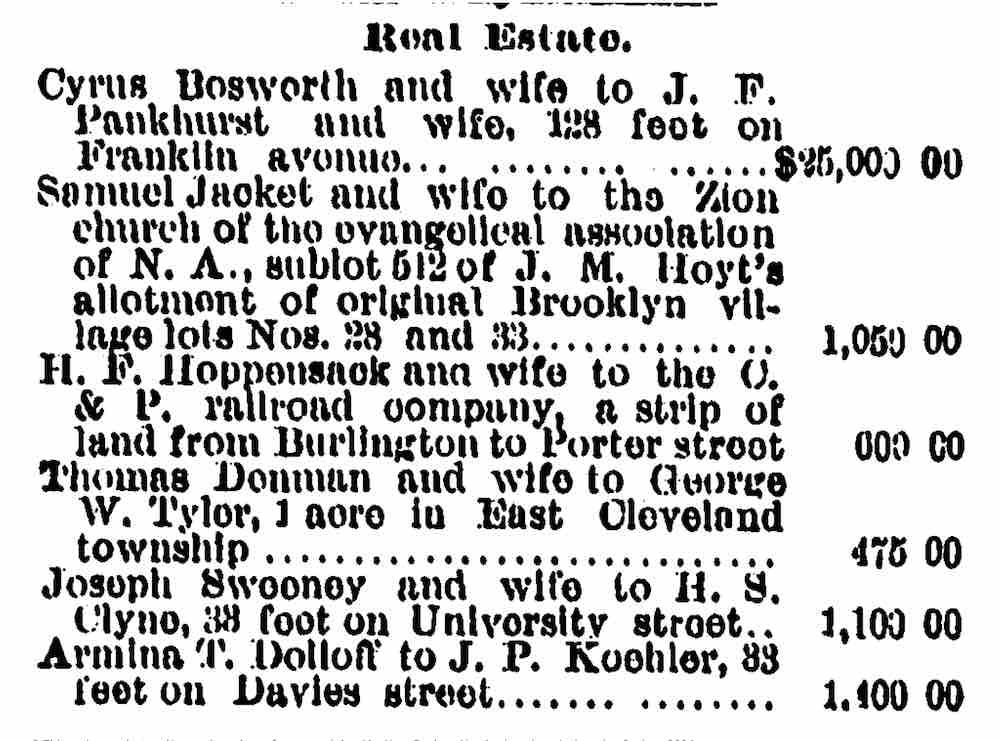

The mansion at 3105 Franklin passed through various forfeiture banks until it was purchased by land speculator Cyrus Bosworth, an heir to Leonard Case. It’s unclear if Bosworth purchased the home to live in or intended to resell it, but in 1885 the property was sold to John Pankhurst, a wealthy proprietor of the Globe Iron Works and Globe Ship Building. Pankhurst’s business partners included Henry Coffinberry and Robert Wallace, who also owned homes on Franklin. After Pankhurst died in 1898, his widow sold the home to John M. Leich, president of Star Brewing Company, for $20,000. It was the last time the home was used as a private residence. In 1913 the property changed hands again. However, this time the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) bought it and the neighboring mansion to the east. In 1928, the year before the onset of the Great Depression, YWCA demolished the mansion to the east and constructed a new dormitory complex of two three-story buildings for single working women to rent rooms. The dormitory buildings were designed by the firm of Howell & Thomas. Howell & Thomas was a small firm that designed many homes in the east side suburbs, including eleven demonstration homes for the Van Sweringen brothers. The firm also designed various YWCA buildings throughout Ohio and Texas.

As the residential wealth that built the homes declined, religious institutions such as the YWCA moved in. Even before the Great Depression, much like the wealthy residents of Euclid Avenue, fortunes diminished and large city homes became less desirable. Franklin Boulevard went from a neighborhood of Cleveland’s elite to mainly working-class immigrants who rented out rooms in converted rooming houses. Many formerly elegant homes were overcrowded and unsightly as a result of housing shortages and the economic downturn of the 1930s. This is best exemplified by the decades-old story of a CWA census worker finding more than 80 people living in the old Belden Seymour home. However, unlike Euclid Avenue, the great homes have mostly persevered throughout this period and have survived despite commercial encroachment in the area.

The YWCA remained at 3105 Franklin until 1957, when the properties were sold to The Sisters of the Humility of Mary, who operated Our Lady of Lourdes Academy just east of the site at 3307 Franklin, which is now an empty lot. The Sisters of the Humility of Mary, a Roman Catholic congregation, were looking to house sisters teaching at Lourdes Academy in the old YWCA dormitories.

Both the YWCA buildings and the Cook-Bousfield mansion were sold again in 1976, after the Academy had merged. The new owners renovated the properties into an elderly care facility for seniors with mental illnesses. It was at this time that an above-ground tunnel connecting the mansion and the dormitories was added, presumably for ease of access for the workers and patients. The tunnel covered the original front entryway of the Cook-Bousfield mansion, and it is likely that the original ornate wooden doors were removed. According to a Plain Dealer article from 1920, the “double doors of black walnut, with ornate carvings of lion’s heads” came from the studio of John Herkomer, who had a shop at Erie (East 9th) and Eagle Street. Not constructed during the period of historical significance, the tunnel has been demolished. When crews were demolishing the tunnel in 2020, they revealed one of the original side porches of the mansion, which may have been turned into a pantry during its institutional days.

Beginning in 2021, the Cook-Bousfield mansion and YWCA dormitory complex were rehabilitated for upscale apartments. There are approximately 38 apartment units throughout the buildings, with an adjoining courtyard. The YWCA complex was gutted and little of the original interior remains. However, due to the project’s tax credit status, the floor plan of the interior is mostly true to the original layout. Many of the historic elements of the Cook-Bousfield mansion, such as the ceilings, flooring, and woodwork, were covered up over time due to its institutional uses. These historic features are rediscovered in the modern setting. The Cook-Bousfield mansion’s conversion into apartments is, simply put, another chapter in its storied life.

Images