The Great Depression had been its downfall, but the end of Prohibition promised a fresh start for a Cleveland luxury automaker. Three years after the last car—a single aluminum-bodied, V16-powered Peerless sedan—rolled out of its plant, the factory-turned-brewery was bottling Carling Red Cap Ale.

Carling Brewery is a story of a company that took the opportunity to use the power of Cleveland as a home of production to reach markets across America and grow its business exponentially. Founded in 1840 by English immigrant Thomas Carling in London, Ontario, Canada, the Carling Brewing Company first entered the U.S. market in 1898 when the Cleveland & Sandusky Brewing Company purchased rights to the Carling name. This lasted only thirteen years.

The brand returned two decades later under much different circumstances. Following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933 the Canadian company saw new opportunity south of the broder and turned to Cleveland. Cleveland proved to be a good choice as Carling’s famous “Black Label Beer” dominated markets for decades. The Carling Brewery and the city of Cleveland benefited from one another and each had a lasting impact on the other. Born of industrial adversity in the Great Depression, the Carling plant itself would become a victim of a new round of economic hardship in the 1970s.

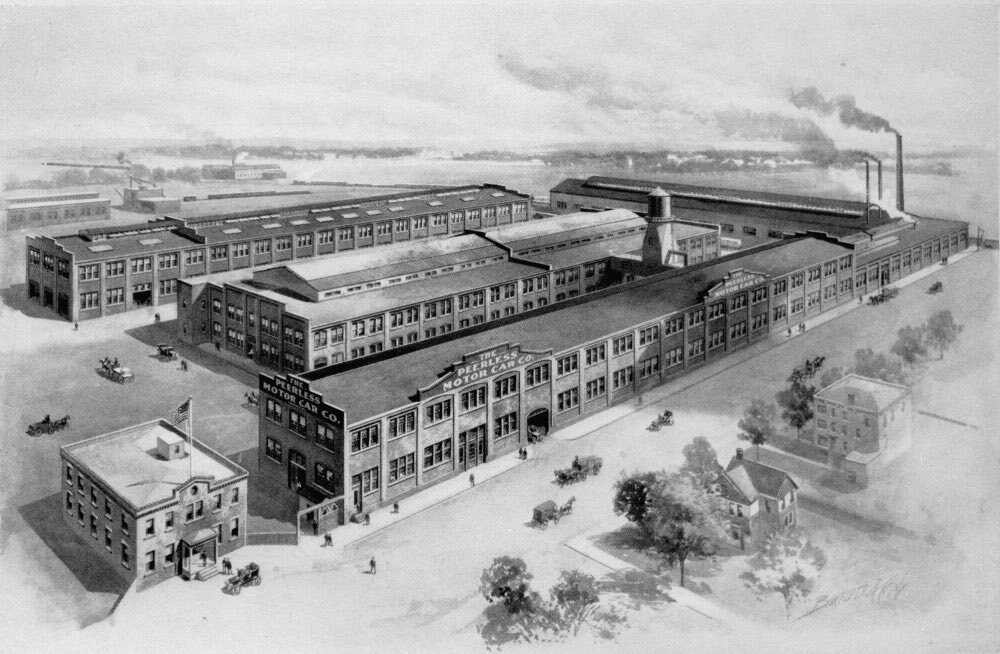

In 1933, Peerless Motor Car Company president James A. Bohannon faced America’s Great Depression head on. Because demand for his luxury cars had collapsed due to the sharp economic downturn, the company’s plant on Quincy Avenue at East 93rd Street, once used to produce these cars, was no longer viable. Bohannon's problem presented an opportunity for him and for Carling. He entered a joint venture that helped Carling expand while promising a new direction for his plant. After incorporating as the Brewing Corporation of America, by 1934, Bohannon's plant that once made luxury vehicles was producing ales that had previously been made only in Canada since the 1840s. In a Plain Dealer article from that year, Harry Smith referred to Cleveland as one of the most modern homes for manufacturing in the world.

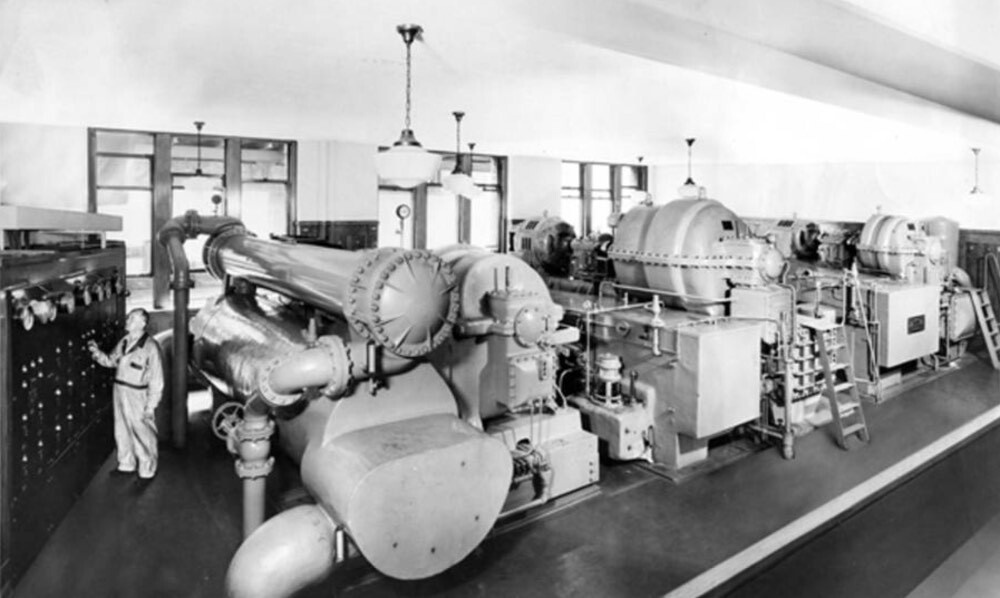

After Bohannon acquired the rights from the brewery, Canadian engineers and brewmasters helped transform the auto plant to a brewery, as well as instruct the new employees on how to make the beer. Though the plant was originally intended for cars, it seems that its transition to brewing was rather seamless, and in no time Carling was selling Cleveland-made beer, first Red Cap Ale and soon Black Label Beer. The plant's transition from car manufacturing to brewing beer essentially proved to be its salvation.

The Cleveland plant, which consisted of a series of long, low-slung brick buildings, was the biggest of Carling’s nine locations throughout Canada and the United States. Cleveland produced an average of 2.2 million barrels of beer annually, which amounted to 68.2 million gallons a year. The Cleveland location also employed 800 people, making it one of the industry’s biggest employers. Not only did the people in the factories make the beer, they had the responsibility of tasting it at every step in the process to ensure it met the expectations of quality.

By 1946, Carling was expanding in Cleveland and rumors arose that the company had planned to buy up a large amount of land in the area and force out homeowners in this corner of the Fairfax neighborhood, which was mostly African American. In a Plain Dealer article that year, an executive from the Cleveland brewery dispelled the rumors by explaining that only thirteen families would be affected by the brewery’s expansion. The Cleveland brewery was proving to be a success, and from 1933 to the start of the 1960s, the company was seeing growth in sales that allowed it to expand to meet demand.

As the Carling brand became increasingly popular, the Brewing Company of America changed its name to Carling Brewing Company in 1954 and began expanding to multiple cities across the country. Opening manufacturing plants in almost every region, the Cleveland plant continued to be the home of the Black Label beer. Through the mid-20th century, brewing local beer was a huge success for the city of Cleveland, sometimes called “the brewery capital of the United States.” As late as 1971, the Plain Dealer could point to over 25 breweries that were at one time producing beer in our own backyard. However, Carling Brewing Company was struggling to keep up with competitors like Miller and Anheuser-Busch, which had emerged as macro breweries, meaning their beer was manufactured and sold in large volume across the United States. These huge brewing companies continued to expand due to their low costs and through acquiring more smaller breweries to expand their command of the beer market.

To maintain their market share, the smaller brewing companies that hoped to remain independent continually had to reduce their prices and spend more on advertising each year. For example, Carling paid dearly for key endorsements like being the main beer sponsor of the Browns and the Indians. As sales declined, Carling had to shut down brewing locations around the country even though many people loved their products. In 1971, the Cleveland plant was among the casualties of insurmountable competition, although another firm, C. Schmidt & Sons of Philadelphia, bought the plant and operated it for another twelve years.

Although Cleveland’s many older breweries like Carling failed to survive the restructuring of the industry, brewing has been picking up again in the area in recent decades, and the larger companies that have emerged since the 1980s – notably the Great Lakes Brewing Company and Market Garden Brewery – have enjoyed success not only in Cleveland but also in the entire Midwest. Breweries such as Carling exemplified that Cleveland can still be a major player in beer production. The local breweries in Cleveland today, while smaller in scale than older ones like Carling, carry on the city’s great brewing heritage.

Images