On a chilly evening in November 1923, hundreds of Clevelanders gathered for a tour of Fenway Hall, “Cleveland’s New Exclusive Apartment Hotel.” The delegation “inspected everything from the Florentine furniture in the lobby to the nutmeg grater in the kitchen of an eleventh-floor suite” and “chatted in Peacock Alley,” a corridor offering interior access to a row of shops and services. Along with nearby Park Lane Villa and Wade Park Manor, Fenway Hall was one of three residential hotels that opened that year on the border between the Doan’s Corners business and entertainment district and the University Circle educational and cultural district.

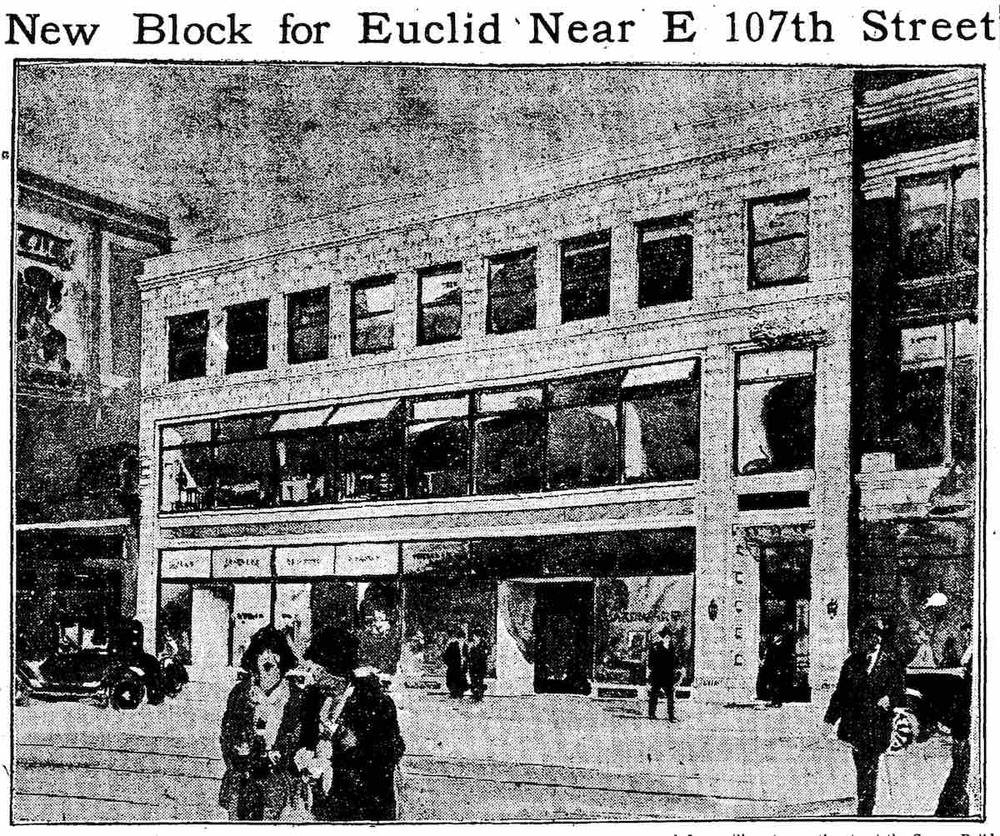

Doan’s Corners had long been a focal point for development in what was East Cleveland Township. In 1799, Nathaniel Doan built a cabin with a pond for watering horses along the stage road between Cleveland and Buffalo, later named Euclid Avenue, just east of its intersection with Doan (later East 105th) Street. In 1817, Doan’s son Job replaced the structure with a larger tavern, later known as Jim Wright’s Tavern. In 1876, Liberty E. Holden and other investors erected the four-story, mansard-roofed Fairmount Court Hotel on the old tavern site. The hotel stood on the northwest corner of Euclid Avenue and the newly cut Fairmount (later East 107th) Street.

After World War I, dozens of storefronts, theaters, and apartment buildings sprouted along Euclid Avenue, turning Doan’s Corners into a veritable “second downtown.” In 1922 the Euclid-Fairmount Co. purchased the former Holden property (by that time owned by the nearby Case School of Applied Science) and commissioned George B. Post and Sons to design a new residential hotel. The New York-based firm had designed the Hotel Statler in downtown a decade before and was also designing Wade Park Manor just to the north. Post’s Georgian Revival design, prepared in collaboration with Reynold H. Hinsdale of Cleveland, guided construction of the thirteen-story, brick and limestone faced, steel-framed, “fireproof” Fenway Hall.

Like other residential hotels, Fenway Hall promised an elegant, convenient lifestyle, free of the burdens of housekeeping. Early ads contrasted its advantages with the headaches of owning a suburban home. “When you pay your rent at Fenway Hall,” one ad observed, “you have also paid the coal man, the ice man, the gas and electric light men, the plumber, the repair man and the electrician, as well as the maid, the flat laundry, etc.” Indeed, Fenway Hall offered all the services that defined hotel living. On its ground floor were a dining room, delicatessen, coffee shop, beauty and barber shops, haberdashery, and, by 1924, Fenway Hall Golf School, staffed by Canterbury Golf Club instructor Jack Way. What’s more, each of its 192 one- to three-bedroom “Bachelor and Light Housekeeping Suites” was amply furnished—right down to linen, silver, china, glassware, and kitchen utensils—by Albert Pick and Co. of Chicago, which did the same for Wade Park Manor.

More than an address for Clevelanders seeking an alternative to a home in suburban Shaker Heights, Fenway Hall was a part-time residence for some wealthy locals who summered in lakefront estates or wintered in Florida, as well as a fashionable destination for out-of-town guests. One hotel ad noted, “transient guests over the holidays are accepted,” adding, “their nearness to your home, while at Fenway, and the completeness of our facilities make this service of real value to those entertaining friends from out-of-town.” Hotel residents shared Fenway Hall’s dining spots with those from across Cleveland and afar. For its part, the dining room advertised Sunday dinners for $1.50 and, in one very detailed ad, highlighted its commitment to locally sourced foods: milk and cream from Maple Leaf Dairy, seafoods from Edward J. Metzger and fruits and vegetables from De Gaetano & Parrino (both in the nearby Euclid-East 105th Street Market), and meats and poultry from Brandt Co. in the Sheriff Street Market.

Within a few years, the dining room was remodeled as the Jade Room. Billed as a “metropolitan supper club,” the Jade Room, with its green walls, yellow tables and chairs, and blend of “Georgian style” and “Chinese ornament,” featured nightly dance band concerts broadcast on radio station WTAM. The Jade Room, later restyled the Coral Room and then the Conga Room, was a popular stop before or after vaudeville shows and movies at the nearby Alhambra, Keith’s 105th, and Circle Theaters. In addition, Fenway Hall welcomed conventions and numerous local club meetings and weddings, and it housed some of the players on the Cleveland Falcons hockey team, which played in the Elysium, a giant indoor ice rink across East 107th Street from the hotel.

In the hotel’s early years, ads had promised jobs for white bellboys, maids, and other staff positions, with the first apparent job open to African Americans—dishwasher—only appearing after three years. Although references to racial qualifications for hotel jobs disappeared by the 1930s, Fenway Hall continued to target the patronage of well-heeled whites. In 1942 the hotel manager grudgingly accepted eleven Black physicians and their wives from Philadelphia as guests while they were in town for a medical convention. But the hotel’s days of exclusivity and exclusionary practices were drawing to a close. The former Doan’s Corners, more commonly called the Euclid–East 105th area, stood on the northeastern fringe of Cedar-Central (later Fairfax), Cleveland’s largest African American neighborhood, and by the 1950s the business district was simultaneously becoming a rare nexus for interracial nightlife and facing the leading edge of disinvestment.

These changes added to the growing challenges residential hotels faced. Affluent Clevelanders’ preference for suburban homes meant that University Circle would not see its Wade Park become Cleveland’s answer to Central Park West. After having been operated by the same company for its first quarter century, Fenway Hall changed hands repeatedly in the two decades after World War II. Despite the modernizations made by each new operator, the hotel was no longer a fashionable address but it remained an anchor for an evolving district. In 1960, E. L. Koenemann, president of Carnegie College at 4707 Euclid Avenue (a training school for medical technologists, assistants, and secretaries), bought the Fenway with the vision of relocating the college to University Circle and housing its students in the old hotel. Instead, under the name Fenway Motor Inn, the property became an economy accommodation for overnight and transient residents.

In November 1966, Marjorie Winbigler, a Cleveland Orchestra chorister who lived in Shaker Heights, disembarked at the bus stop outside Fenway Hall. Before she could reach Severance Hall on foot, she was assaulted and murdered in Wade Park. Combining with white racial fears elevated by the Hough rebellion earlier that year, the crime alarmed University Circle leaders. Case Institute of Technology and Western Reserve University purchased Fenway Hall and the nearby Tudor Arms Hotel months before the schools merged in 1967. They sought these buildings to provide graduate student housing but also to remake the western fringe of University Circle. However, following a subsequent decision to build new dormitories on Cedar Hill, Case Western Reserve University divested itself of Fenway Hall in 1975. The City of Cleveland paid CWRU $840,000 for the hotel and then resold it to University Circle Inc. (UCI), for $710,000, thereby letting the university avoid a loss. UCI hired the Orlean Co. to turn the building into a federally subsidized elderly housing development named Fenway Manor, which reopened in 1978.

Today Fenway Hall sits in a very different context. The Euclid–East 105th district yielded to the transformation wrought by the Cleveland Clinic’s relentless expansion, leaving the old hotel as the lone survivor from the district’s heyday, although recent and planned high-rise apartment developments promise to create the apartment row that never fully materialized along Cleveland’s Doan Brook park belt a century before.

Images