Creator: Clay Herrick Date: 1982

"Everybody’s doing a brand new dance now; come on baby, do the locomotion!" Sound familiar? It’s the cover hit, "The Locomotion," by Grand Funk Railroad. The band recorded many hit records, as did many other bands during the 1960s and 1970s, including The James Gang and Wild Cherry. These three bands had one thing in common; their hits were recorded and produced at one location - the Cleveland Recording Company. The Cleveland Recording Company operated during a time of technological advances in music recording. The CRC produced local and national hit records, helping shape Cleveland's growing reputation as a musical capital.

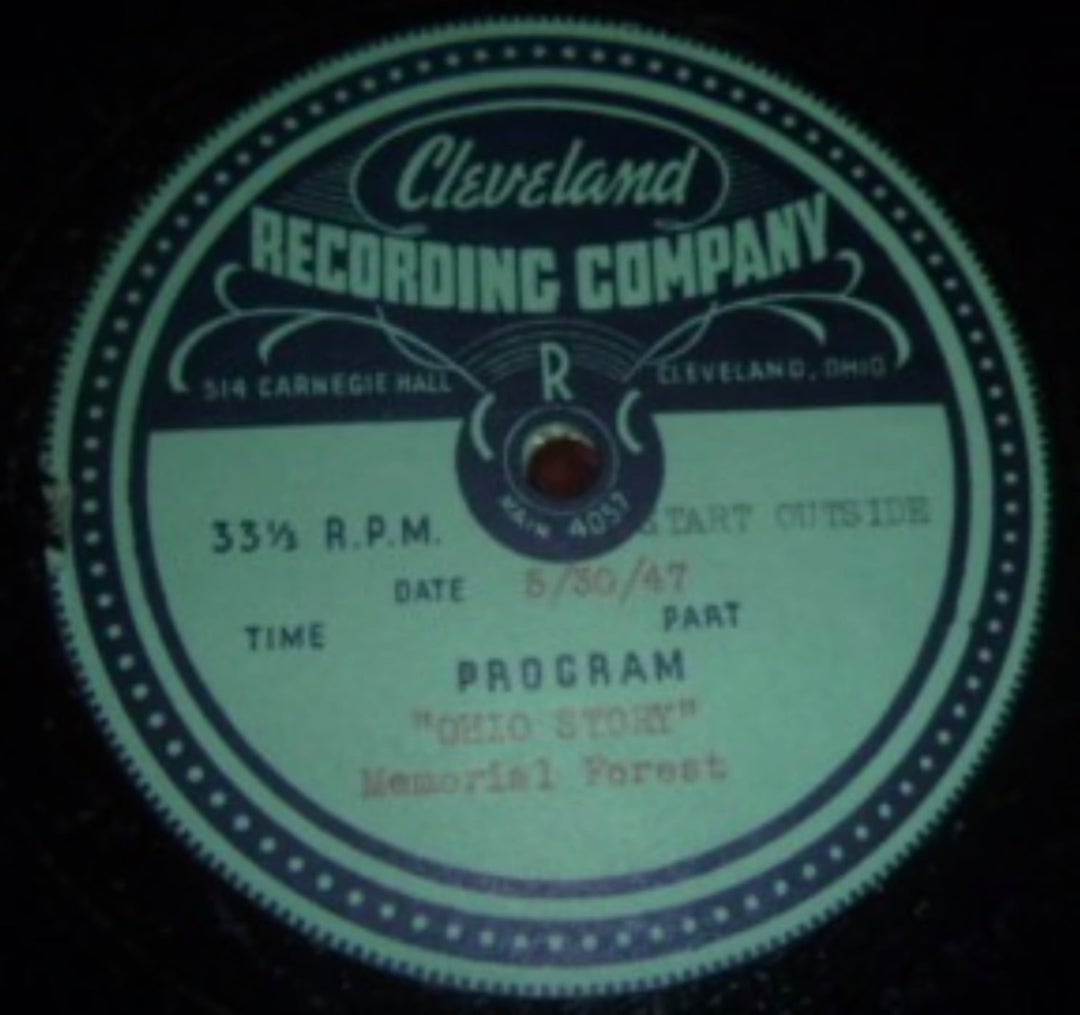

In 1934, Frederick C. Wolf founded the Cleveland Recording Company, first located in the Carnegie Hall Building at 1220 Huron Road, which had been built as a multistory auto garage before being turned into an office building, marketed primarily to performing arts organizations. A native of Prague, Czechoslovakia, Wolf accompanied his younger brother James to the United States; while James went to Chicago, Wolf stayed in Cleveland. Wolf developed a dream of ethnic radio broadcasting, so in the mid-1930s he purchased transcription equipment from Crystal Recording. Once set up, Wolf and his friends moved into the space at 1220 Huron, broadcasting classical music and polkas. Since Cleveland was known as the "Polka Town," every Sunday Wolf and company broadcast their respective half-hour shows of eastern and central European polkas.

Of the many polka groups that recorded in Cleveland, the most well-known was Frankie Yankovic, the future "King of Polka." Yankovic started working with Wolf in 1938, recording some of his first polkas at Cleveland Recording. Yankovic joined the Army in 1943, leaving little time to continue his recording sessions. Yankovic recalled that "there wasn’t any time to fool around; if we got a note wrong, we just had to keep going. But I insisted we leave the clinkers in, because people like it better that way." When Yankovic left, Wolf held on to some of Yankovic’s money until he returned.

In 1947, a Chicago real estate operator purchased the Carnegie Hall Building, including its common stocks and open spaces. This purchase also meant a name change—from Carnegie to the Huron Building. The transition prompted Cleveland Recording to move into the fourth floor of Loew's State Theater, at 1515 Euclid Avenue. Wolf was no engineer, so he needed additional help working on Cleveland Recording’s technology. So, in 1950 Wolf hired Ken Hamann. After he left the Navy, Hamann received an FCC operators' license and accepted an open position at WDOK, another radio station Wolf founded the same year. Once there, Hamann used his skills in aviation electronics, inventing and building his own recording equipment.

By the late 1950s, Hamann worked to improve the recording process at Cleveland Recording. Like other hi-fi hobbyists, Hamann experimented on what was called the "ping-pong stereo" method, recording environmental sounds on an Ampex 2-channel recorder the studio had. The process involves combining multiple tracks into one, mixing together and overdubbing on track recorders. This included recording sounds at Euclid Beach Park and its roller coaster. Hamann played with other types of recording equipment. He experimented with recording sounds using a 3-channel recording system. Clients for Cleveland Recording varied from high school students to professional musicians, and every time a recording session took place, Hamann tried to improve the recordings and upgrade the technology. Hamann worked so much Wolf promoted him to chief engineer by 1956.

In the late 1960s, Wolf's health began to decline, but he continued to help with Cleveland Recording. Due to his struggling health, Wolf sold Cleveland Recording to Hamann and fellow engineer John Hansen in 1970. Hamann had known Hansen since high school and worked with him in his early years at WDOK. However, local talks about a new parking garage to replace Loew's State Theater made Hamann and Hansen move the Company to a new place; this time to 1935 Euclid Avenue, previously known as the Corlett Building. Although Ray Shepardson and allies ended up saving the State Theater, Hamann and Hansen took no chances. They received help from a Cleveland bank to occupy the old Chevrolet auto space, home to what was more recently the Cleveland Cadillac Company (1925-1965), and Hamann and Hansen’s families with local construction works helped renovate the space into a studio. It was there that Cleveland Recording produced some of the most well-known hit records of the 1960s and 1970s.

Thanks in part to Hamann’s innovation in recording technology, the music to come out of Cleveland Recording was known locally and nationally. Hamann and Hansen were quick to see the potential of local artists, where Hamann stated in the Plain Dealer, "The area of Ohio, Michigan, and West Virginia has been rich in talent." The artists that came to Cleveland Recording not only brought talent, but new ideas to bring into the recording process. Bands ranged from local (The Human Beinz, The Lemon Pipers) to national (Grand Funk Railroad, The James Gang).

In 1977, Cleveland State University bought the property at 1935 Euclid, which meant another expensive move for Cleveland Recording. Hamann and Hansen disputed over money issues. Musicians were notorious for being poor-paying customers, compared to the more "straight-laced" commercial clients. Hamann described the "divorce" of Cleveland Recording between himself and Hansen. The studio was separated into two main sections; one for music, run by Hamann, and the other commercials, run by Hansen. Hamann allowed most musicians and bands to stack up their bills, driving Hansen antsy. The two split up the equipment; Hansen took whatever he thought was needed, and Hamann took the rest.

Hansen took the name of Cleveland Recording Company and continued producing radio and commercial jobs until his passing in 1990, which led Cleveland Recording to go out of business. However, it gained a successor when Hamann created Suma Recording, located in Painesville. When Hamann died in 2003, his son Paul Hamann took over until he passed away in 2017. Suma Recording is still open, with recording equipment available for use via appointments.

The Cleveland Recording Company contributed significantly to the national music scene of the 1960s-1970s. Once Frederick Wolf opened CRC in 1934, polka and classical music played on the radio, yielding to rock and roll in the 1960s and funk in the 1970s. Ken Hamann's technical prowess and innovation created sounds unheard of at the time, sending bands of the Midwest into national stardom. This spreading of popular music shaped the city of Cleveland into a hub of entertainment, continuing to this day through Suma Recording and other recording studios. The Cleveland Recording Company really did "play that funky music."

Images

Creator: Clay Herrick Date: 1982