East View United Church of Christ

On November 1, 1970, Reverend George Ramon Castillo and his wife were received into the membership of East View United Church of Christ. The ceremony marked the occasion of Reverend Castillo being installed as the first Black pastor of a Shaker Heights church. Presiding over the service, Rev. John Huston passed on a mission of expanding the fledgling house of worship to his successor with a sermon titled “A Man for This Time.” When Huston accepted the post just four years prior, the future had appeared bleak for the small church. The congregation had not been able to afford a full-time pastor for over six years, during which time membership dropped from 550 to under 100. The congregation held votes on whether to disband or move to a new site in both 1959 and 1965. Each time, however, members chose to stay at the present location. The aging institution, with over half its members in their sixties, was financially distressed and facing atrophy; change was needed to remain relevant and survive.

Although East View would only find stability following 1979 through the efforts of Rev. Valentino Lassiter, the church was given new life by Huston and Castillo’s pastoral leadership between 1966 and 1973. Membership numbers slowly rose during these years, and the church was rescued by the new African American community it served and represented. A rapid demographic shift in the surrounding Shaker Heights community was at the heart of these changes; regional and national efforts by the United Church of Christ to promote integration within both its congregations and society provided the backdrop to realize this transformation. This moment of transition required that East View reach out to its surrounding community and address what the United Church of Christ recognized as the most pressing moral issue of the day: promoting racial equality by breaking down race barriers and battling the discriminatory behavior inherent in a segregated society.

The troubles that accompanied declining church membership were nothing new for East View by the 1960s. While many Cleveland religious institutions shuttered their doors or relocated as congregants increasingly moved to the city’s outer suburbs following World War II, living within a rapidly changing neighborhood was par-for-the-course for East View church members. Transformation was illustrative of life in the dynamic Moreland neighborhood, imprinted on the community's design as a stepping stone into the exclusive world of Shaker Heights. Since its founding in December of 1912, seldom had extended stretches of time passed for the Protestant congregation when either an empty pulpit or financial distress wasn’t following closely behind. A contributing factor to these lurking obstacles, as well as the congregation’s resilience, was the church location: the religious institution was born and grew up along the ever-morphing Kinsman Road. Within the first year of the congregation’s founding, members briefly worshiped at a storeroom near East 139th, quickly moved to a six-room home on East 143rd, and finally purchased a lot on 142nd Street (Elm Street) where a stucco building was constructed.

Formally named East View Congregational Church, the thirty-member organization was received into the Cleveland Congregational Union in January of 1913. The small band of founders came from households of Bavarian, German, English and Manx descent, and held jobs such as a factory foreman, rolling stock laborer, steel mill clerk, paint factory tester, and motorcar machinist. The streetcar line running down Kinsman Road not only connected the City of Cleveland with Chagrin Falls, but allowed these workers to live in the semi-rural environs of East View Village.

While land west of East 140th Street was annexed by Cleveland in February of 1913, the area remained fairly undeveloped until the 1920s. The congregation spent its first decade at this border of Cleveland and East View Village. The area would develop outward from Kinsman Road during these early years. On the Cleveland side, population grew in bounds and extended east towards East View Village. Known as Mount Pleasant and Kinsman Heights, the neighborhoods predominately attracted eastern and southern Europeans; they also included one of Cleveland’s few Black enclaves. To the east of the small church, the Van Sweringen brothers were purchasing all the available lots and farmlands in East View Village that their agents could acquire at a reasonable price.

With East View Village’s population never growing much beyond 600 persons, the pool of potential recruits for East View Congregational Church was severely limited during its first decade of existence. A growing Jewish and Catholic community of neighbors along Kinsman Road in Cleveland didn’t increase the odds for growth either. Despite these evangelical limitations, the congregation slowly increased and an addition to their building was constructed in 1918 for use in programs such as Sunday School. The church struggled to retain their leadership throughout this time, and often relied on support from the Congregational Union of Cleveland to assist with salaries. During periods between the revolving cast of pastors, it was common for visiting ministers to arrive at the church only to find a handful of attendees. In 1919 and 1920, the congregation voted on whether to disband. Both times it was decided to persevere despite financial hardship. To save money, East View began sharing a pastor with the struggling United Church Congregational Church in 1920. Additionally, joint services were held with local Methodist Episcopal congregations during summer months.

By the end of 1922, East View was once financially again able to employ their own pastor - the congregation’s sixth in ten years; with the hiring of Reverend John Logan, the church would find a period of relative stability between 1922 and 1929. Although characterized as a “man without the slightest suggestion of gifts as a speaker,” the new minister offered patience, persistence and administrative capabilities. This set the stage for the congregation to not only grow, but embark on a campaign to build a new place of worship. In June of 1923, the members of East View Congregational Church unanimously voted to sell their property on East 142nd Street and relocate a half mile to the east on Kinsman Road.

East View Village was no more by the time the congregation voted to move. The area surrounding East View Congregational Church had been annexed to Cleveland in September of 1917, as well as additional sections of the village being acquired by the city in February of 1919. With much of their lands gone, residents of East View Village voted to be annexed by Shaker Heights in November of 1919. The church on 142nd Street sat within Cleveland, and the ruralesque character of Kinsman Road was beginning to change as the Jewish and Italian communities grew and migrated eastward. Similar to the residents of East View Village, the small church congregation looked towards the restrictive suburban community of Shaker Heights to be their new home. Herbert C. Van Sweringen, treasurer of the Congregational Union of Cleveland, assisted East View Congregational Church in finding the new location. The brother and occasional employee of Oris and Mantis Van Sweringen encouraged the congregation to choose land in Shaker Heights, and negotiated the purchase of a lot of land and farmhouse where the church now sits.

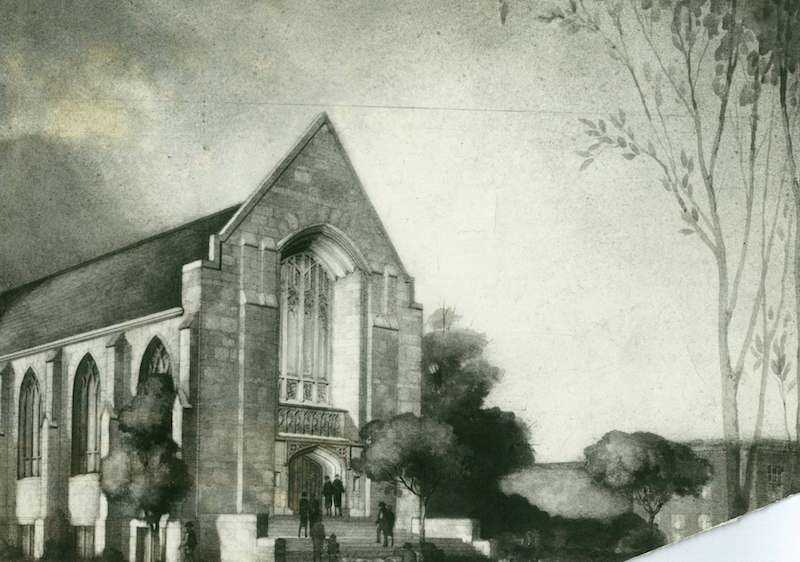

By March 1924, the deal was complete and East View’s congregation acquired the Gibbs homestead at East 156th and Kinsman Road. The farmhouse was used by the congregation while construction of the new structure was underway, and later sold in order to help pay for the new church. Reverend Logan then began the laborious project of scraping together the necessary $100,000 in funding to move forward with church building plans. This proved difficult as the congregation only consisted of 195 members, but they held high hopes for expanding their institution within the rapidly growing Village of Shaker Heights. The only competition for the church would be the more affluent Plymouth Congregational Church, which was miles away and served a “different constituency.” While encouraged to keep their eye on the goal, East View was advised by the Congregational Union against taking steps toward construction in 1926. Undeterred, the congregation proceeded to reduce their expenses by convinced the Church Building Society and Congregational Union to provide the necessary loans and approval. The final cost of the new structure was $60,000. On February of 1928, a capacity congregation attended the dedicatory rites for East View Congregational Church in Shaker Heights.

Having successfully utilized his skills to build a home for the East View congregation, Reverend Logan “wisely left to open the way for a man capable of building a larger congregation” in 1929. With a pristine building in the rapidly growing village of Shaker Heights, the church was finally positioned to thrive. Then came the next stumbling block for the working and middle-class congregation: The Great Depression. A brand-new debt in tow, the congregation found themselves in a financial struggle that lasted through the 1930s. Not all was bad, however. With salary supplements from the Congregational Union, the church procured a dedicated full-time pastor willing to work for below average wages. Membership grew to above 300 by the mid-1930s. Membership collections, on the other hand, plummeted.

The anticipated expansion of the church was checked by changes to the areas surrounding the Moreland neighborhood. Throughout the 1930s, the population of Mount Pleasant along Kinsman Road rapidly grew and expanded eastward. As part of a member canvas performed by the congregation in 1935, a census of the community a half mile distance from East View claimed that 80 percent of residents were either Catholic or Jewish. By 1939, the church reached what they viewed as the “maximum strength of 275 members including children and young people” from about 100 families. Congregants contributed this ceiling to the continued influx of Italian families into the community. Anticipated annual collections were only between $3,000 and $3,500 that year, as at least 25 percent of families were either unemployed or on relief. The “distressing condition” of outstanding loans was accompanied by the physical deterioration of the building, which was in need of a cosmetic makeover and some minor repairs.

The church fared much better over the next two decades as America’s economic depression ended and organized religion experienced a revival following World War II. The 1940s brought the creation of multiple auxiliary groups to foster the social, professional and religious development of its membership. Church grounds were improved in 1942 as the congregation contributed time and labor during a drive to prepare for the institution’s 15th anniversary. Members also undertook a campaign to eliminate indebtedness and pay off $16,000 of outstanding loans in 1944. In December of that year, the congregation burned its mortgage.

The impact of the war went beyond just bringing in new church members and temporarily ending economic woes. To the west of East View, the area along Kinsman Road was undergoing a new demographic shift. African Americans from the South migrated en masse to northern cities during and following World War II to meet demands for industrial labor. Cleveland’s Black community grew from 85,000 in 1940 to 279,350 in 1965. While Cleveland’s African American population was highly segregated in the Cedar-Central neighborhood, the community quickly reached outwards towards Kinsman Road. Discriminatory lending and rental policies similarly shaped the population movement and segregation of working class and poor African Americans along the inner city’s east side.

The African American enclave in Mount Pleasant had already expanded to as many as 700 families by 1940. Lacking deed restrictions or restrictive covenants, this long-standing Black community continued to attract middle class and professional African Americans with the financial resources to move away from the deteriorating and over-priced inner-city housing. Simultaneously, both physical and economic pathways such as new highway infrastructure and the G.I. Bill presented much of the city’s white and European-descendant communities the opportunity for suburban home ownership. The Kinsman Road Jewish community began to disperse, moving further east into both Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights neighborhoods following a U.S. Supreme Court decision making deed restrictions illegal in 1948. Cleveland’s border with the Moreland neighborhood and East View church was predominately African American by 1960. Beyond a small population of live-in domestic help and a grouping of about 80 black families in the Ludlow neighborhood, however, Shaker Heights remained nearly all-white. While East View Congregational Church was listed as open to integration in 1957 by the Congregational Union of Cleveland, congregants that year determined that segregation was not yet a pressing problem for their church. Church members decided against taking any type of action at the time to address the issue.

As the problem of segregation was increasingly brought to light by a national civil rights movement, the small church faced institutional changes. In 1957, Congregational Christian churches merged with the Evangelical and Reformed church to create the United Church of Christ. East View voted to join the United Church of Christ in 1961, although the delay was not unique. The process of creating, redrafting and receiving approval for a church constitution took time: meeting the needs of 1,419,000 Congregationalists and 810,000 Evangelical and Reformed Church members, in over 8,000 semi-autonomous congregations, proved to be a long and labor-intensive undertaking. With a united leadership, however, the national institution could provide a stronger voice promoting its religious and social agendas. National, state and regional offices were also better equipped to offer financial support to economically distressed institutions such as East View Congregational Church.

At the time of joining the United Church of Christ, East View Congregational Church was once again financially troubled. The aging congregation was led by an interim pastor completing studies at Oberlin Theological School. While congregants previously voted to both remain open and not relocate following the resignation of their pastor due to health issues in 1959, church membership decreased dramatically. Demographic changes in the Moreland neighborhood during the 1960s presented the congregation a new chance for growth. Moreland transitioned from a nearly all white community to over two-thirds African American by the end of the decade. Previous problems of growing the church in a predominately Catholic and Jewish community no longer applied as this wave of Protestants settled into the neighborhood; issues of integration and segregation could no longer be ignored, however, if the church wished to remain relevant to its surrounding community.

Despite declining membership, the path to integration was not clearly laid out and little changed for the church until the mid-1960s. The issue of segregation and race, however, became the primary national social cause for the United Church of Christ after its Fourth General Synod in 1963. With civil rights legislation being filibustered in the U.S. Senate, and a mass movement pivoted against segregation visibly displayed on America’s streets, issues of racial justice were at the forefront of the nation’s consciousness. Informed by studies and over 20 years of work by sociologists at Fisk University’s Race Relations Department, the United Church of Christ narrowly approved a new policy at its annual national conference that helped define the progressive character of the church going forward. The newly formed United Church of Christ would cut off all funding to churches that practiced segregation. Additional efforts to advance racial justice were also approved that provided legal aid to demonstrators, developed scholarships for African Americans, supported civil rights legislation, and promoted voter registration drives.

Born from a union of the Board of Home Mission of the Congregational Christian Churches and the Board of National Missions of the Evangelical and Reformed Church, the United Church of Christ-affiliated United Church Board for Homeland Ministries was charged with administering and leading the efforts to desegregate all churches within the year. Open membership covenants were sent to all members, but it was soon discovered that the demands for integration had little effect at the local level. A 1964 survey indicated that churches were still discriminating against African Americans, even if by not soliciting for new memberships. Only one-third of United Church of Christ churches were open to all races. Outside of the South, the Midwest had the smallest proportion of integrated congregations at 6.6 percent. Problems in the North rested with its highly segregated society: white churches sat in white neighborhoods, and few African Americans were available for membership.

Since East View Congregational Church was located in a rapidly integrating neighborhood of Shaker Heights, and bounded on the West by a predominately African American section of Cleveland, the struggling church presented an opportunity for the United Church of Christ to develop a strong interracial congregation. In 1964, the Board for Homeland Ministries voted to provide substantial financial support for this project in Shaker Heights. State and regional associations of the United Church of Christ also offered financial assistance to the endeavor of integrating East View; the United Church of Christ’s regional governing body, the Western Reserve Association, undertook a research project and set aside money to assist with hiring a full-time minister and developing a complete church program. The pastor-less East View congregation consisted of 145 members at the time, and its membership only included three Black families.

After a year of declining membership and financial troubles, the church received its new full-time pastor. In January of 1966, it was announced that John Huston would leave his 1,000-member congregation in Lorain, Ohio to take up the cause of rebuilding East View Congregational Church. Huston was known for his anti-poverty and race relations work in Lorain, and chosen for the Shaker Heights “interracial project” because of his commitment to civil rights. In leaving the large church where he had spent over a decade, the pastor wished to concentrate on his ministerial role as a counselor while earning a doctorate in psychology.

East View membership had fallen to just 95 members at the time Huston stepped into his new role. A publicity campaign was immediately initiated to let residents of the surrounding community know that the church desired to be integrated. As part of reinventing the church, the congregation changed its name to East View United Church of Christ. After-school programs and Sunday School, both of which had disappeared over the prior decade, were reinstated. Church doors were opened for daily use by community service groups and area students. Huston’s stated goal was to build a symbol of friendship and service, thereby dispelling any distrust or suspicion the community had about the institution. The efforts were met with success over the following year. Huston successfully engaged local youths to participate in a youth choir and multiple charitable volunteer programs. He also implemented an integrated nursery school program that proved popular with parents wishing to give their children a chance to play with youngsters of different races. Organizations such as the Scouts, Brownies and Moreland Community Association used the church space on a formal basis, while neighborhood children took advantage of an open invitation for after-school play and study groups.

Between 1966 and 1970, Huston continued his efforts to advocate for racial and economic justice. The church would be used as a dialogue center to host group discussion of racial problems, and two college students working at East View coordinated support for the Poor People’s Campaign and Operation Breadbasket. Huston also acted as a member of Mayor Stokes’ Citizens Advisor Committee for Community Development, and worked with other United Church of Christ ministers to develop ways of dealing with problems of urban renewal, police regulations, discrimination in housing and unemployment, and school integration. Huston expanded his role for the United Church of Christ in 1968 to fill a vacancy of pastor for another struggling parish, the Immanuel Church of Shaker Heights.

National and regional efforts of the United Church of Christ during the late 1960s also continued to focus on promoting race relations and battling discrimination both within the church and in society. Rooted in the premise that the church had a responsibility to remain active in promoting civil rights, the Board of Homeland Ministries continued to allocate its financial resources to support efforts at breaking down racial barriers. New programs aimed to recruit civil rights workers to fight a rise in terrorism by southern segregationists. Recognizing shortcomings within the church, a committee of Black ministers was formed to act as a pressure group in 1966 to give a stronger voice to the church’s African American membership and address the limited opportunities available to ministers of color.

As the 1970s drew near, increased national focus was placed on promoting social and economic opportunities for African Americans and promoting racial pluralism. The church also began using its economic and social influence to advocate for an end to the Vietnam War, combat apartheid, draw attention to ecological exploitation, and fight gender discrimination. At the regional level, efforts were made to invest United Church of Christ funds in Black-owned businesses and promote church development in African American communities. Localized attempts to improve race relations also continued, as through the development of a Western Reserve Association task force to identify ways of eliminating conscious and unconscious white racism within the church structure. Much of the regional group’s focus on issues of racial discrimination receded in the 1970s, though, as other pressing issues of church development arose.

In a 1967 letter posted to Martin Luther King Jr., John Huston wrote, “I have felt that unless I did something significant in the area of racial justice I would have been wasting much of my life.” Huston found this calling in his work with Operation Breadbasket, a selective patronage program implemented by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference that was meant to improve economic opportunities in African American neighborhoods. A little over a year later, hoping to find “a greater opportunity to work in race relations, helping to achieve justice in our society, reconciliation and understanding,” Huston submitted his written resignation as pastor of both East View and Immanuel Church. During his brief stay at East View, both the church and the neighborhood had transitioned to becoming predominately African American. Church membership stabilized at around 145 members and the day nursery program continued to be popular within the Shaker Heights community. The small church, however, still required financial assistance from both regional and national offices for survival.

In November 1970, Rev. George Castillo replaced John Huston. Castillo, who had previously held a pastorate in Detroit, was brought into the church with a track record of recruiting new members, working with youth, and developing educational activities for the community. Newspapers accounts reported that Sunday service attendance doubled during his brief stay at East View United Church of Christ, although general membership numbers dropped slightly. The pastor expanded upon United Church of Christ efforts to reach out to the Moreland community; a new Sunday School program was initiated, and the church began offering day care services to working mothers. He also helped found the Western Reserve Association’s Criminal Justice Committee of the United Church of Christ, acted as chaplain of the Warrensville Workhouse, and was a member of the Ohio Black Minister’s Conference. In June 1973, however, the pastor assumed new duties as a chaplain for the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary in Georgia. Castillo was soon after replaced by Rev. Michael Barker, but the remainder of the decade presented new obstacles to the small church’s survival.

As the popularity of institutional religion waned over the 1960s, and eventually fell below pre-Cold War averages in the early 1970s, regional and state offices of the United Church of Christ were forced to explore budget cuts. In this changing environment, East View United Church of Christ found company in its difficulties attracting both steady pastoral leadership and hordes of new congregants. Over 75 percent of Western Reserve Association congregations had less than 300 members by 1974. East View faced additional financial burdens that year, however, having received notice from the City of Shaker Heights of building code violations. The repairs would cost at least $10,000, and the small church needed to take out new loans from both the Board of Homeland Mission and the Western Reserve Association to cover them.

The Board of Homeland Ministries quickly renewed its commitment to the small church during this time of crisis. In part due to the efforts of Castillo and Huston in opening the church to the surrounding community, East View was one of only a handful of churches in Ohio representative of the United Church of Christ’s goals of promoting church desegregation and fostering racial pluralism in its ranks. The Western Reserve Association held the highest percentage of African American membership of any Ohio conference at three percent, primarily because this governing body placed value on its affiliation with churches such as East View United Church of Christ, Hough Avenue United Church of Christ, Shaker Heights Community Church, and the People’s Church in East Cleveland. The Transitional Church Committee was formed in 1975 by the Western Reserve Association to research strategies for aiding these east side churches. The committee developed plans to help the congregations become self-sustaining, and provided each church five years of financial support to be divided by and paid through the United Church of Christ’s regional, state and national offices.

With financial assistance in place, the congregation was once again confronted with the all-too-common problem of an empty pulpit. Reverend Barker accepted a calling in Chicago to act as pastor in September 1976. East View faced plenty of competition in attracting new leadership; eleven Western Reserve Association churches simultaneously had vacancies of either pastor or assistant-pastor that year, four of which were on Cleveland’s East Side. East View remained without a full-time minister until the installation of Reverend Valentino Lassiter in September 1979. Church membership fell to 79 persons. Lassiter later recollected that, upon becoming the new pastor, Sunday services rarely attracted more than twenty-five persons.

Starting from scratch, the new pastor personally reached out to the surrounding community and began slowly re-growing the congregation. Using fliers and word of mouth, Lassiter worked to revive interest in the small church. Even after more than a decade as a predominately African American congregation, the new pastor found many neighborhood residents did not know that East View aimed to serve the surrounding community. As in the past, the church was opened to the community for use by clubs and community service organization such as the Scouts and Moreland on the Move. Departing from precedent, though, the new pastor slowly revamped services that were steeped in traditional Congregational practices to take on elements of the Black church and African American worship. Within a decade of Lassiter's arrival, church membership had expanded to over 200 persons. More importantly, Sunday masses — with the church's gospel choir sitting high above the pulpit — was regularly filled with just as many joyful attendees. Beyond the popular children's and gospel choir, East View United Church of Christ offered its growing congregation a variety of opportunities for civic, religious and social involvement. Church members advanced the formation of a large bible study group, held a popular annual community essay competition, and cultivated a variety of women's and men’s social clubs.

Rev. Lassiter also kept busy. The full-time pastor began work in John Carroll's religious studies department shortly after the completion of his theology doctorate in 1989, where he eventually became the pastor in residence. In addition to his day jobs, the pastor participated as a member of a variety of community groups including Moreland on the Move, the Interchurch Council of Greater Cleveland, the Harambee Board, the Mt. Pleasant Ministerial Alliance, the Moreland Community Association Credit Union, the Greater Cleveland Roundtable, and the 25th District advisory committee.

Valentino Lassiter continued to act as pastor of the parish until his death in the summer of 2015. Under his leadership, the United Church of Christ's mission for the small parish was finally achieved. The church had become a vibrant religious institution within the community it served. Rev. Lassiter's leadership and thirty five-plus year tenure as pastor offered a stability that allowed the church to not only evolve under his guidance, but to be both shaped by and representative of its congregants' lives, experiences and interests.

Images