Cleveland once ranked as one of the nation’s leaders in garment manufacturing, thanks in large part to the Cleveland Worsted Mills. An immense sight in its heyday, the plant suffered years of neglect and decline after its closure, until a fire destroyed much of the complex. Today the industrial giant is largely forgotten, but the impact it had on Cleveland and environmental laws has remained.

In 1878, Joseph Turner started the Turner Worsted Mill, renamed the Cleveland Worsted Mill in 1902. The Cleveland Plant, located at 5932 Broadway Avenue, handled every aspect of the worsted cloth process, from scouring and sorting wool to boiling the cloth. At the height of production in the 1920s, the mill ran more than 500 looms and consumed 25-35,000 pounds of wool daily.

As one of the leading employers of the area's large immigrant population, namely Poles and Czechs, the company expanded rapidly. In 1908 it completed a $200,000 addition, including a six-story brick steel factory building and a three-story office building. To ease employee concerns about safety, it constructed exterior stairways and elevator shafts in the new building and also added elevators in existing buildings. With the addition the facility became the second largest plant for worsted production in the country.

Despite its national recognition and financial success, the company had a difficult relationship with its employees. In 1934, the plant closed for almost three months due to striking over union discrimination. In 1937, complaints were made against the company for “terrorizing and intimidating employees” to keep them from joining the Textile Workers Organizing Committee and workers again went on strike for a few weeks. Striking broke out again in August 1955, brought on by a breakdown in talks between company officials and the Textile Workers Organization. Rather than continue talks, Cleveland Worsted Mills chose to liquidate its assets in January 1956.

Although the company was gone, disaster struck the plant again in 1993. In April, investigators found 100 barrels of potentially hazardous materials left improperly stored in the warehouse complex. The material was found to be flammable and reports state the building had no working sprinkler system. Investigators determined that the barrels would remain in the building until they knew what they contained and who was responsible for them as there was some dispute over who owned the property. While city officials were trying to determine who owned the property, an arson fire destroyed the complex on July 4. City fire officials were aware of the danger the barrels within the mill presented and had already devised a plan to fight the blaze they correctly figured was inevitable.

As a result of the fire, new laws were put in place with tougher punishments for environmental offenders. It became a crime for companies to walk away from a site without cleaning up contamination. Moreover, the courts could force them to pay for the cleanup, and any damage incurred was the company’s responsibility. Environmental nuisances were added to the state's nuisance abatement laws that allow the state to take over such properties.

The city spent $3 million to clean up the debris from the fire and fill in the land. A few years later, it became the Boys and Girls Club of Cleveland. The organization runs a recreational and educational site on more than five acres of the 12.5-acre complex.

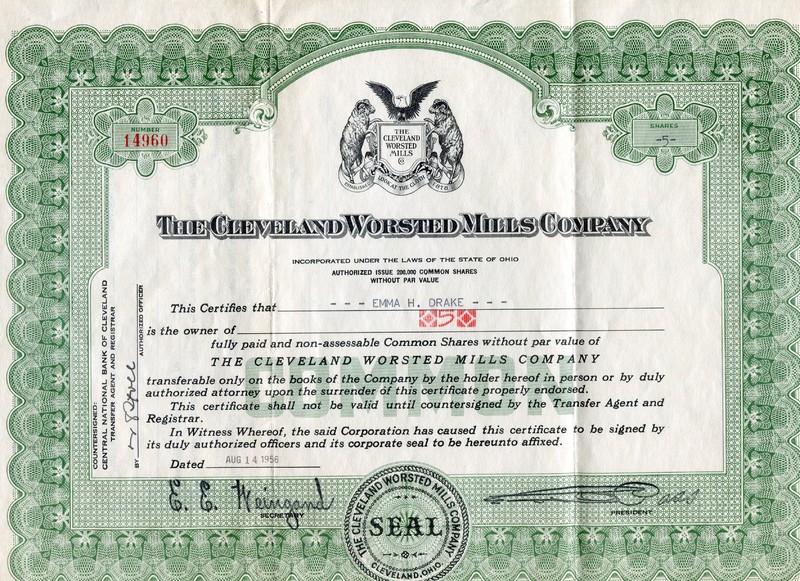

Images