Although today the first sign of downtown that a motorist is sure to spot from any direction is the Key Tower, prior to its completion in the early 1990s the first sight was the Terminal Tower. Despite its eclipse by a later, taller skyscraper, the 52-story, 708-foot-tall Terminal Tower was an instant icon and has arguably remained Cleveland’s most potent symbol. The Terminal Tower, at least as a plan, didn’t start as a tower at all, but instead as a railway station known as the Cleveland Union Terminal. In the early 20th century, as Cleveland grew as an industrial powerhouse, many Northeast Ohioans used railway lines to get to their destinations. Ohio had one of the most extensive interurban networks, with over 2,000 miles of track. However, it was not commuter railways but rather intercity passenger trains that led to the creation of the Terminal. Steam locomotives produced excessive amounts of pollutants when converging downtown, hampering Cleveland’s goal of becoming a modern, attractive city. In the interest of smoke abatement, the Union Terminal project would rely on switching trains to electric engines at outlying rail yards before passing through the city, including its central rail terminal.

The only problem was where to place this symbol of Cleveland’s progress. Inspired by Chicago’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, Cleveland Mayor Tom Johnson and the Group Plan Commission began planning a “civic center” that would run from Superior Avenue all the way to the lakefront. This civic center centered on the Mall and was Cleveland’s dominant expression of the City Beautiful. But the plan to make a new railway along the lakefront as the grand point of entry to the city came to a halt because of unexpected developments. Enter the Van Sweringen brothers, Mantis J. and Oris P., a duo of real estate and railroad tycoons who were keen on connecting their master-planned suburb of Shaker Heights to downtown via a new rapid transit rail line.

While the Van Sweringens originally planned the Shaker Heights line, their ambition expanded. The brothers realized that for the station for Public Square to succeed, they needed to include railways and facilities next to it. After heated debates that lasted a few years, the Terminal cornerstone was set on March 16, 1927, tilting downtown Cleveland’s center of gravity decidedly back to Public Square and ending the concept of a Mall anchored by an imposing rail station. The project was estimated at around $170 million and the Union Terminal had its grand opening in 1930. Travelers to Cleveland found many shops and services inside the Terminal’s concourses without having to step outside, including the elegant English Oak Room, Fred Harvey Company concessions, Higbee Bros. department store, and the preexisting adjacent Hotel Cleveland. The 42nd floor was used as an observation deck, allowing a bird's-eye view of the city. The Terminal’s concept of a multiuse “city within a city” anticipated New York’s Rockefeller Center. The Van Sweringen brothers, never comfortable in the spotlight, did not attend the 1930 dedication, instead spending the day at Roundwood Manor, their country estate in Hunting Valley.

The Terminal Tower itself was built toward the end of the skyscraper craze of the 1920s. When completed in 1930, it was the tallest tower in the world outside New York City. If the “Vans” wouldn’t toot their own horn, there were plenty of others ready to trumpet the Terminal’s superlative status. Walter Ross, president of the Nickel Plate Railroad, effused that the tower was “the symbol of the city’s progress and the prophecy of its future. … Cleveland may be sixth in the census list of cities, but so far as its Union Station is concerned, if that is any consolation, it may regard itself as on a parity with the leading city.”

However, the completion of taller buildings in other cities periodically whittled down this superlative: to tallest in North America outside New York after 1953 and tallest between New York and Chicago after 1964. When Key Bank Tower was completed in 1991, the Terminal Tower became the second tallest in Cleveland and second tallest between the Big Apple and the Windy City. Nevertheless, the Tower’s architecture is something to behold, with the upper portion closely resembling New York’s Municipal Building. Both were modeled on ancient Roman types called sepulchral monuments, a favorite classical nod associated with the Beaux-Arts architectural movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Ironically, by the time Cleveland’s iconic tower was built, even the Beaux-Arts style was antiquated as more architects embraced the emerging Art Deco and other modernist modes.

The choice of an older style of architecture may have reflected a desire to make downtown Cleveland appear more well-established. After all, despite the steady rise of skyscrapers on the skyline since the 1890s, Cleveland’s skyline had fallen further behind a handful of the nation’s other largest cities by the late 1920s. Although it was hardly an original and audacious design apart from its towering height, over the next few decades, the Terminal Tower grew to be a defining status symbol for Cleveland. The self-contained “city within a city” of interconnected buildings—all linked to the same central transit station—made for daily interactions with those who worked there. In 1970, the president of Terminal Management, Homer Guren, mentioned how his employees became “sort of a Tower family.”

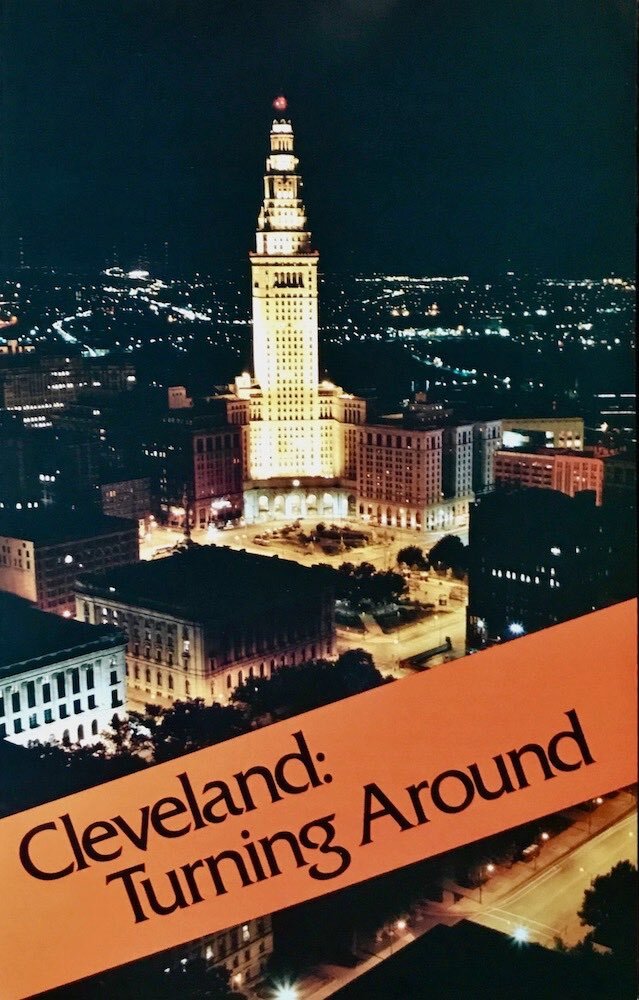

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Terminal Tower became a symbolic place in many other ways as well. To support the Cleveland Indians, twelve baseballs were dropped from the roof to the ground below. Only two of the balls thrown by third baseman Ken Keltner were caught by catchers Hank Helf and Frankie Pytlak. The Indians’ special treatment didn’t stop there, as the team’s flag flew atop the Tower during home games. In 1980, after Mayor George Voinovich’s election amid Cleveland’s long, painful slide in the 1970s, the Terminal Tower was illuminated from base to crown at night to symbolize the city’s comeback. The building adorned the logo for Yellow Cab taxis for many years, frequently found its way into Harvey Pekar's comic books, and was featured in the background of many television shows and movies, most notably the 2012 hit The Avengers.

More recently, the Terminal Tower has taken on a modern aesthetic, not just for the look, but to show support for the community. Thanks to the addition of LED lights in 2014, the Tower is lit up every night in a range of different colors: for the Cleveland Cavaliers, wine and gold; for the annual Pride celebration, rainbow; and even colored images like the Leg Lamp from A Christmas Story, which was filmed in Cleveland. During the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, the Tower staged a special light show to signal hope for the city. The ever-changing colors of these lights keep Clevelanders’ eyes focused on the skyline, helping reinforce the Terminal Tower as an enduring symbol of the city.

Video

Audio

Images