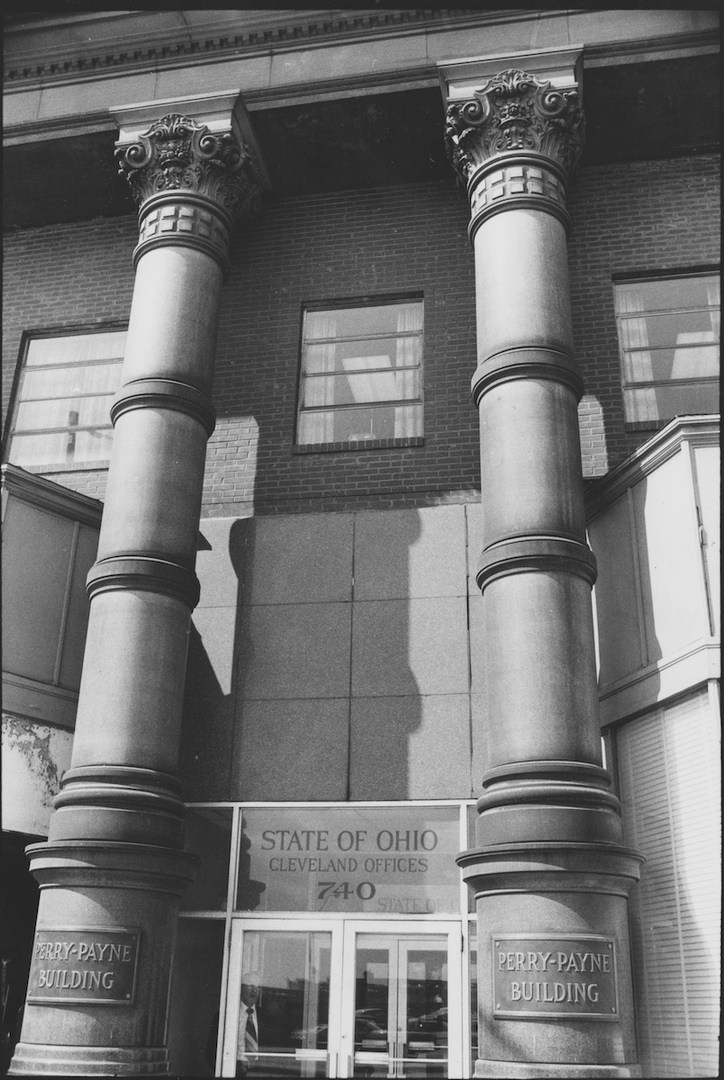

In the Spring of 1887, workmen tore down a number of three-story commercial buildings that had long stood on the north side of Superior Street between the National Bank Building on the northeast corner of Superior and Water (West 9th) Street and the Scovill Building (formerly the Franklin House), located midway up the block. The site was cleared to make room for the construction of the eight-story Perry-Payne Building. A little less than a year later, while the new Perry-Payne Building was going up, an article appeared in the Plain Dealer on April 15, 1888 recalling those earlier buildings and noting that "while the old must give way to the new," a number of Cleveland's most prominent pioneer merchants, including William Bingham and George Worthington, had started their businesses in the old buildings and that therefore "the place is of historic memory."

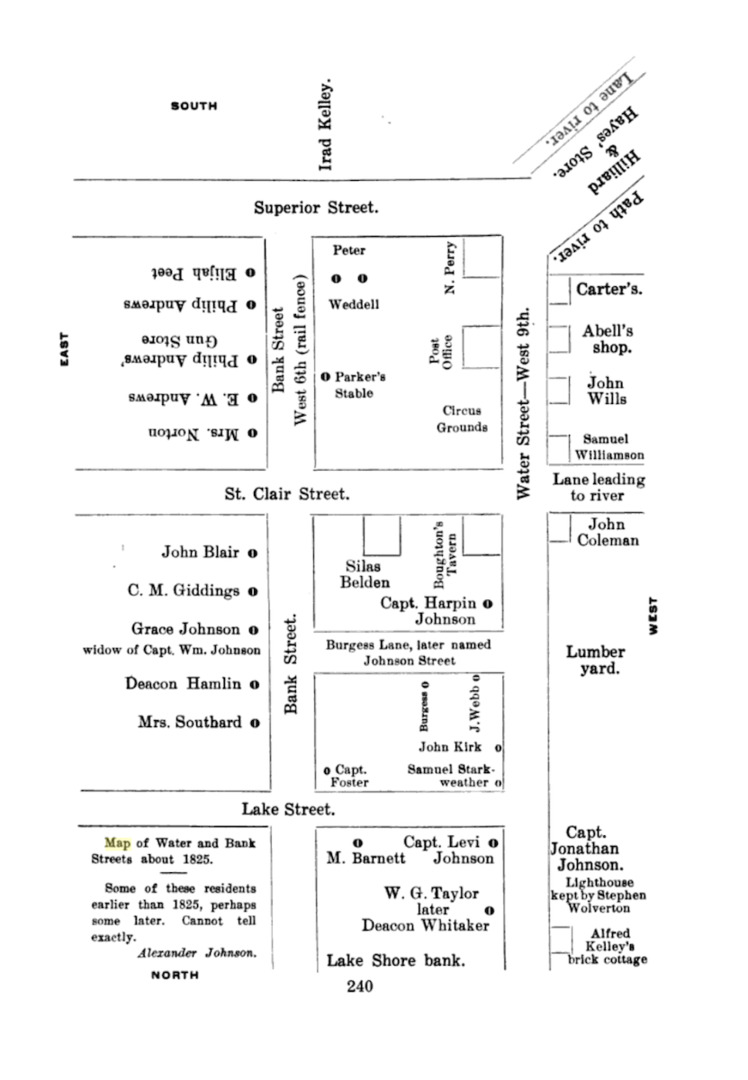

The historic land upon which the Perry-Payne Building at 740 W. Superior Avenue stands, and much of the land that surrounds it in Cleveland's Warehouse District, was first commercially developed by the Nathan Perry family. Nathan Perry Sr. (1760-1813) was an innkeeper in western New York's Genesee County when, in 1796, he was hired by Moses Cleaveland to provide food supplies to the surveying party that founded Cleveland. Almost a decade later, he, his wife Sophia, and their children moved here. In 1806, Perry purchased six acres of land northwest of the Public Square. On that land, which had frontage on Superior, St. Clair and Water (West 9th) Streets, Perry opened a trading post in a cabin that stood less than fifty feet from where the Perry-Payne Building stands today.

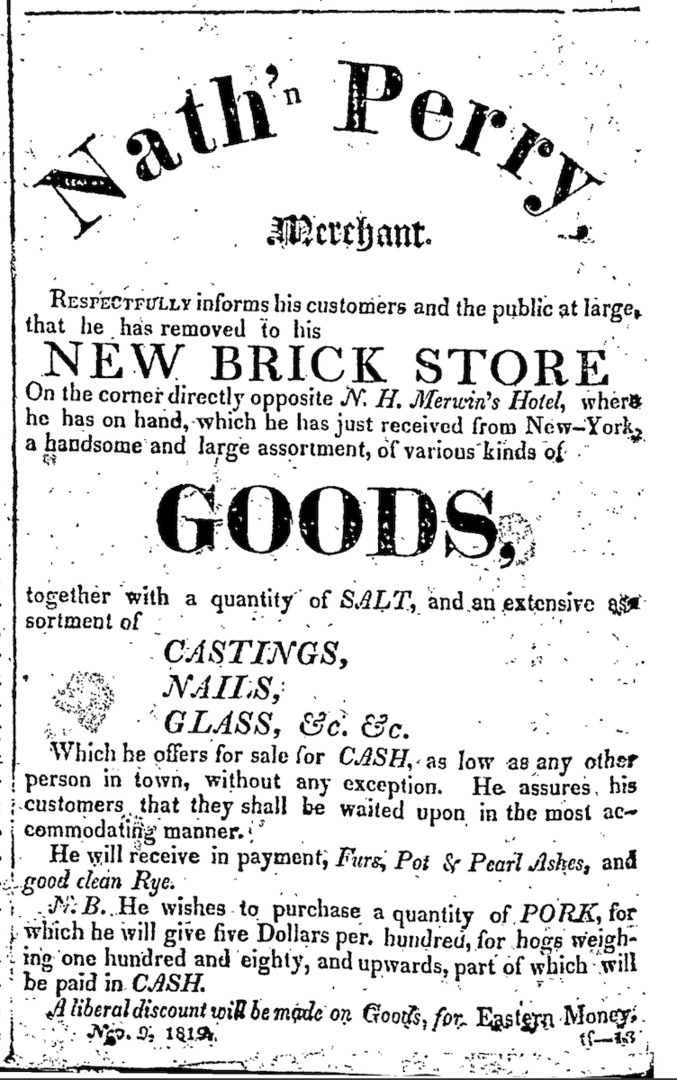

Nathan Perry, Sr. was one of Cleveland's first merchants. Less than a decade after arriving in Cleveland, however, he died unexpectedly. Four of his six acres, including the land upon which the Perry-Payne Building stands, passed to his son Nathan Perry Jr. (1786-1865), who transformed his father's trading post into a dry goods store and, in 1819, replaced the cabin with a two-story brick commercial building, one of Cleveland's first. Nathan Jr. operated his dry goods business in that building until 1826, when he sold the business but retained ownership of the building and the land upon which it stood.

In addition to running his dry goods business, Nathan Perry Jr., as early as 1814, had been making shrewd purchases of land in Cleveland, and, by 1830, he had become one of the city's wealthiest landowners. In that latter year, he moved his family from the simple frame house they had lived in on Water Street, just north of his dry goods store, into an early-era mansion on Euclid Avenue. It stood where Berkman Hall stands today on Cleveland State University's campus, just east of East 22nd Street.

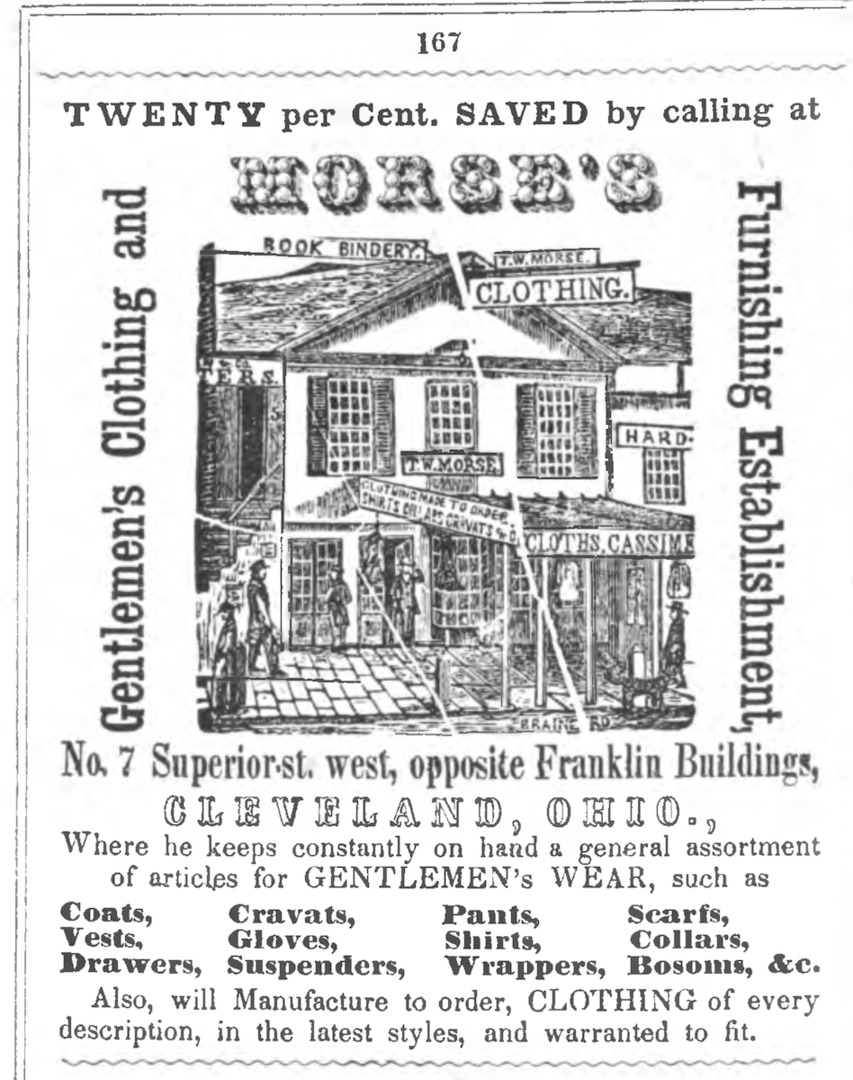

In 1835, Perry decided to lease some of his land near the corner of Superior and Water to two hardware merchants, William Cleveland and Elisha Sterling. The terms of their two leases—drawn up by a young Cleveland lawyer named Henry B. Payne—required them to construct two three-story brick commercial buildings on the land they leased. Each of the two brick buildings they built had two storefronts. The buildings with their four storefronts became known as the "Central Buildings" because the corner of Superior and Water was then the center of Cleveland's commercial business district. It was in these buildings that William Bingham, George Worthington, and other prominent early Cleveland merchants, who were mentioned in the Plain Dealer article of April 15, 1888, got their business start.

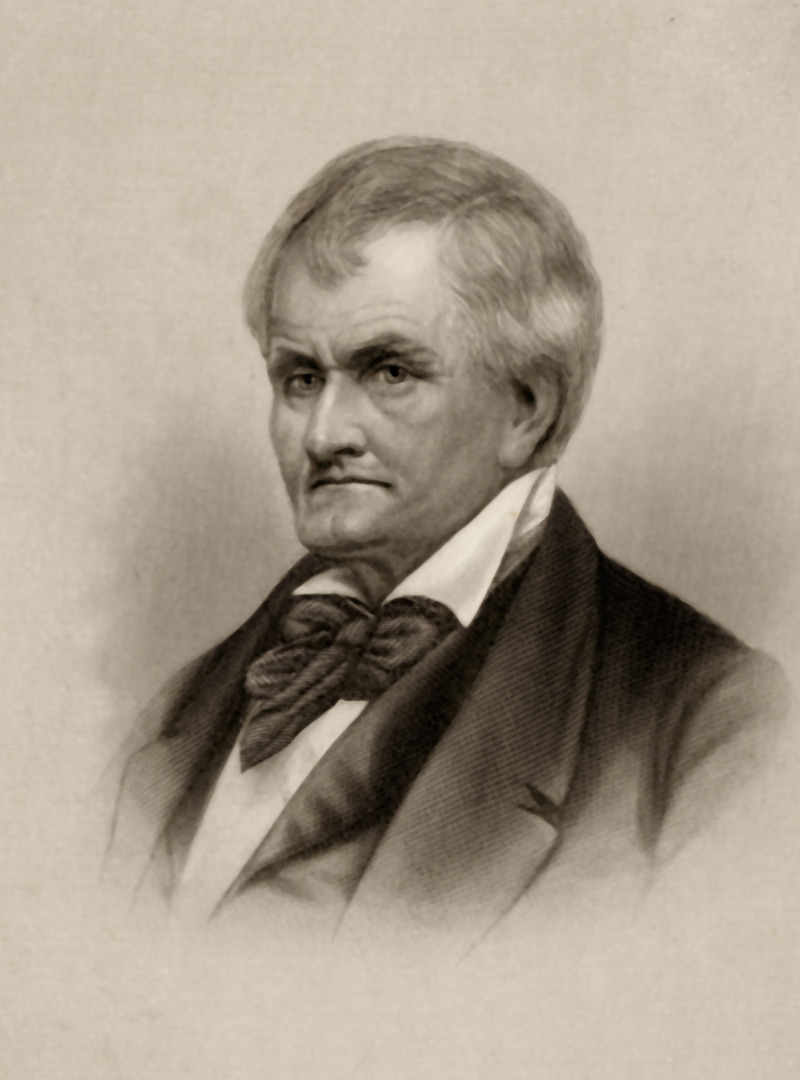

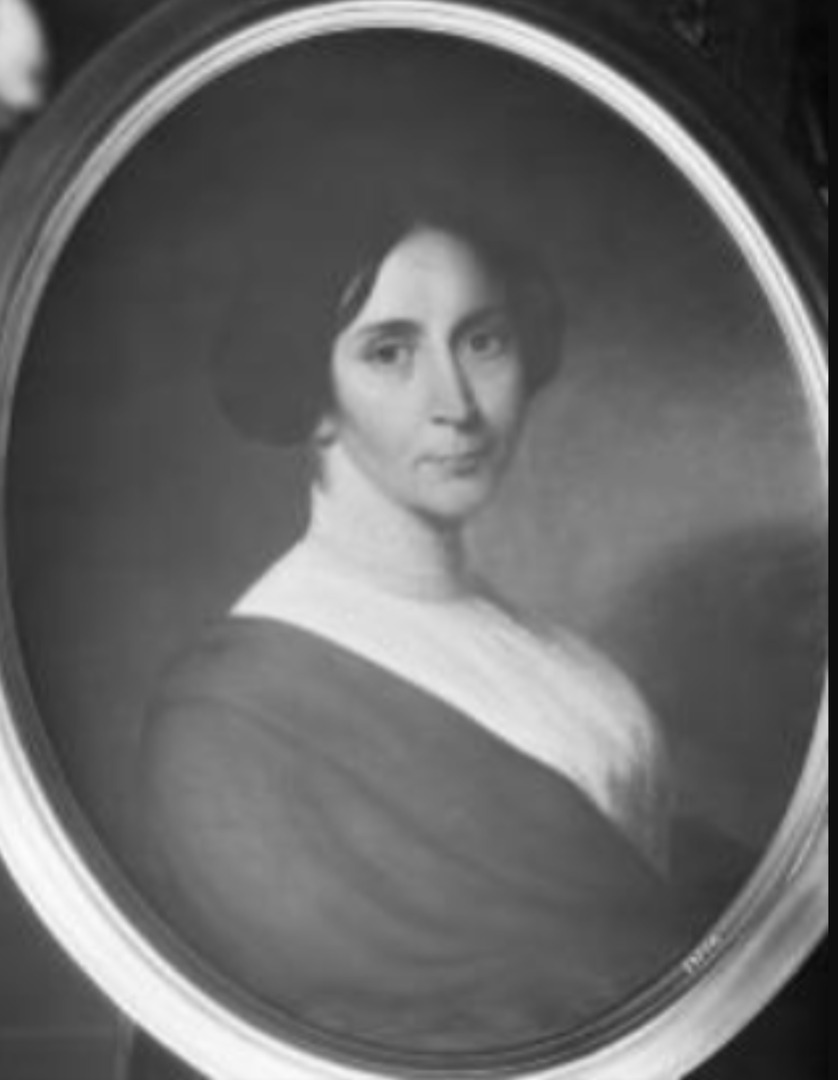

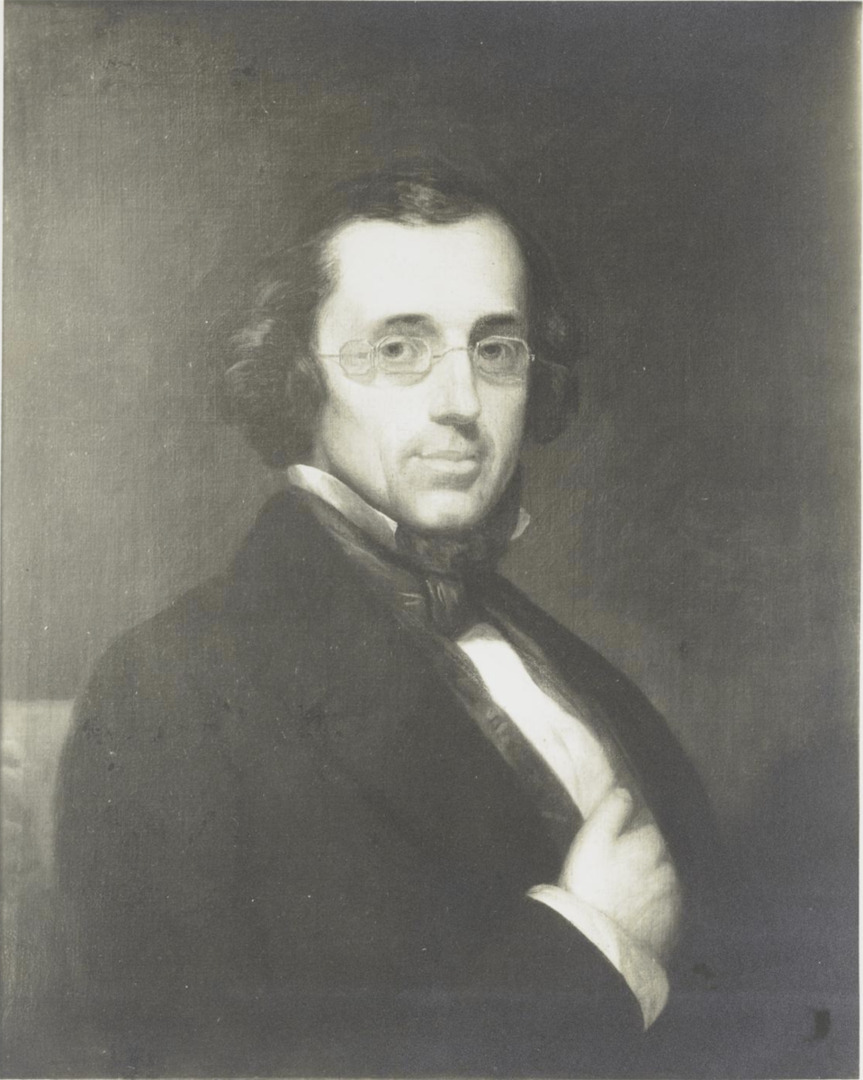

As important as the Central Buildings were to the enlargement of Nathan Perry Jr.'s real estate portfolio, lawyer Henry B. Payne, who drafted the leases that required they be built, would soon become even more important. In 1833, Henry B. Payne was a law student in Hamilton, New York, when he was impelled to travel to Cleveland to help nurse his best friend, Stephen A. Douglas, who was suffering from a severe illness. Douglas, who later became the Illinois Senator whom Abraham Lincoln famously debated in 1858, left Cleveland after recovering. Henry Payne chose to stay. Payne completed his law studies here and, in 1836, when Cleveland officially became a city, Henry Payne became its first solicitor. In August 1836, Payne, who had in 1835, as noted above, served as Nathan Perry's lawyer, married Perry's only daughter, Mary, who thereafter became known to all in Cleveland as Mary Perry Payne.

Henry Payne practiced law in Cleveland for more than a decade before he decided to leave the practice. In 1849 he joined forces with Alfred Kelley and Richard Hilliard to build Cleveland's first railroad, the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati ("CCC"). In the process, he became that railroad's first president. In 1855, Payne turned his attention to government service and was appointed to the City Waterworks Commission. It built Cleveland's first waterworks system. Then, in 1862, he took on the work of chairing a city sinking fund board which reportedly stabilized Cleveland's finances for years. Henry Payne also became active in local and state politics. He served in a number of Democrat party positions, before being elected in 1874 to the United States House of Representatives. A decade later, in 1885, he was elected Ohio's first United States Senator from Cleveland.

It was during the second year of Henry Payne's term as a United States Senator that local newspapers reported that Senator Payne was planning to build a new commercial building on Superior Avenue that would be named the Perry-Payne Building. Different reporters and different historians writing in different eras have speculated differently as to the reason why Henry Payne named the Perry-Payne Building as he did. They all, however, may have been looking to the wrong person for an answer to their question.

When plans were made to build the Perry-Payne Building, the land upon which it was to be built was owned by Mary Perry Payne. The decade of the 1880s was one in which American women were beginning to acquire greater property rights, including the right to own, develop and dispose of real property in their own name. Henry B. Payne was uniformly said to be a progressive person of kind disposition who had a very loving marriage with Mary Perry Payne. Given all of the foregoing, there is no reason not to believe that Mary Perry Payne, probably with her husband's full support, was the person who chose the name of the building that was to be built upon her land. So perhaps the question that we should ask today, even if it was not asked by newsmen in 1887, or by historians thereafter, is: Why did Mary Perry Payne choose to so name her building? While we do not know the answer to that question with any degree of certainty, it might be as simple as that was where she first met Henry Payne.

In proceeding with their plans to build the Perry-Payne Building, Henry and Mary Perry Payne selected Cudell & Richardson, one of Cleveland's most prominent late nineteenth-century architectural firms, to design it. Cudell & Richardson, in additional to this historic building, also notably designed the following buildings still standing in Cleveland: St. Stephen Roman Catholic Church on West 54th Street; Franklin Circle Christian Church at 1688 Fulton Road; Belden Seymour Block at 2513-2525 Detroit Avenue; Franklin Castle at 4318 Franklin Boulevard; the George Worthington Company Building at 802-832 W. St. Clair Avenue; the Root and McBride Building at 1220 West 6th Street; and the Bradley Building at 1212-1224 West 6th Street. Additionally, Cleveland's Cudell Commons Park and the city's Cudell neighborhood are both named after Frank Cudell, one of the two named partners in that architectural firm.

The building Cudell & Richardson designed for Henry and Mary Perry Payne was described in a June 19, 1887 Cleveland Leader article. It was to be constructed "of brown stone and granite, in the Rennaissance style of architecture. The side and rear walls will be of brick. . . . The floor joists will be of iron and the floors fire clay tile. . . . [T]he stairs will be made of iron and cement or marble. Iron balconies will be provided on the fifth and seventh floors." The article stated that the building would be "eight stories high in the middle and seven on either side, with a basement. It will have a frontage of 138 feet, a depth of 100 feet, and will be 120 feet high." The article noted that the first floor of the building would be designed for the offices of banks, and the upper floors would have a total of 46 offices with an average size of 18 x 26 feet.

Other articles noted that the interior of the building would feature an eight-story interior court illuminated by a sky light. (The design of this light court, as well as the building's front facade, were reminiscent of Chicago's Rookery Building designed by Burhnam and Roots.) Other interior features of the Perry-Payne Building were its modern elevators and mail chutes that carried mail from all of the building's upper floors down to a first floor mail room. Designed with interior iron support columns, the Perry-Payne Building is notable architecturally as a transitional building between earlier buildings with masonry support walls and later buildings, including the Society for Savings Building erected just one year later, having interior steel support beams which enabled them to be built to great heights and led to them becoming known as "skyscrapers."

Construction of the Perry-Payne building commenced in the summer of 1887 after all of the old commercial buildings on the site had been razed. While construction was expected to be completed in 1888, financing difficulties encountered by Henry and Mary Perry Payne appear to have delayed completion of construction until the summer of 1889. The first tenants of the Perry-Payne Building included Bingham Hardware and National City Bank, who opened their offices in the new building on July 1, 1889. When the Perry-Payne Building opened, it was the tallest and most grand commercial building in Cleveland, and it attracted many of the largest iron ore, coal, and shipping companies in Cleveland as tenants. It also attracted a number of Cleveland law firms, including a new firm named Squire, Sanders and Dempsey (today, Squire, Patton and Boggs), which has since become one of the city's largest and most historic law firms.

In the first two decades of its existence, even as larger and grander commercial building went up in downtown Cleveland, the Perry-Payne Building continued to attract more than its fair share of Cleveland's coal, iron, and shipping-related businesses, as well as a number of law firms and insurance companies. However, almost all of its core tenants departed after 1913 when Marcus Hanna's son Dan completed his construction of the enormous 15-story Leader Building on the corner of Superior Avenue and East 6th Street. Thereafter, for decades, the Perry-Payne Building survived with much less than full occupancy.

During its early years, ownership of the Perry-Payne Building remained with the Perry-Payne family and their descendants through the Perry-Payne Company formed in 1899, several years after the deaths of Henry and Mary Perry Payne. However, in 1945, that company sold the Perry-Payne Building to another corporation that was unrelated to the family. The building had many new owners in the years that followed and these new owners struggled to find and hold onto tenants. Then, in 1965, the State of Ohio leased the entire building for a number of its agencies with offices in Cleveland. This, however, only temporarily solved the building's occupancy problems for, in the summer of 1979, the State agencies departed when the new Frank J. Lausche State Office Building, directly across the street, opened.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, the owners of the Perry-Payne Building struggled anew with occupancy problems. In 1994, however, a new partnership purchased the building, hired an architectural firm known for its restoration work, and proceeded to restore the front facade of the Perry-Payne Building; renovate the remainder of it; and convert it into an apartment building with 91 apartments and 8,000 square feet of retail space. As of the writing of this story in 2024, the Perry-Payne Apartments remain a prestigious address in downtown Cleveland's Warehouse District.

If Mary Perry Payne were alive today and learned that her Perry-Payne Building had been converted into an apartment building, she might say that it really didn't matter, so long as Clevelanders today believe, as she and her husband and Clevelanders of her generation more than a century ago believed, that the Perry-Payne Building stands at a place of historic memory.

Images