At a 1947 testimonial dinner at the Phillis Wheatley Association to honor African American businessman Willie Pierson, John O. Holly, the president of Cleveland’s Future Outlook League, said, “If we had a few more Willie Piersons, this community would be almost self-sustaining.” Indeed, by investing in a number of businesses in the 1930s and ’40s with an eye toward creating opportunities in the city’s Black community, Pierson had become one of Cleveland’s most influential Black leaders of his time.

Willie Pierson was born in Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory, in 1898. After serving in World War I, he migrated to Cleveland’s Cedar-Central neighborhood, where he operated a pool room. Over the ensuing years, he garnered a reputation as a “numbers racketeer” and, in the process, amassed considerable wealth. At a time when African Americans struggled to get access to credit, engaging in lotteries and other forms of gambling was a common way to circumvent systemic exclusion. But like his better-known contemporary Benny Mason who operated the famed Mason’s Farm club in Solon, Pierson would not simply grow wealthy but also use his wealth to invest in Black community advancement.

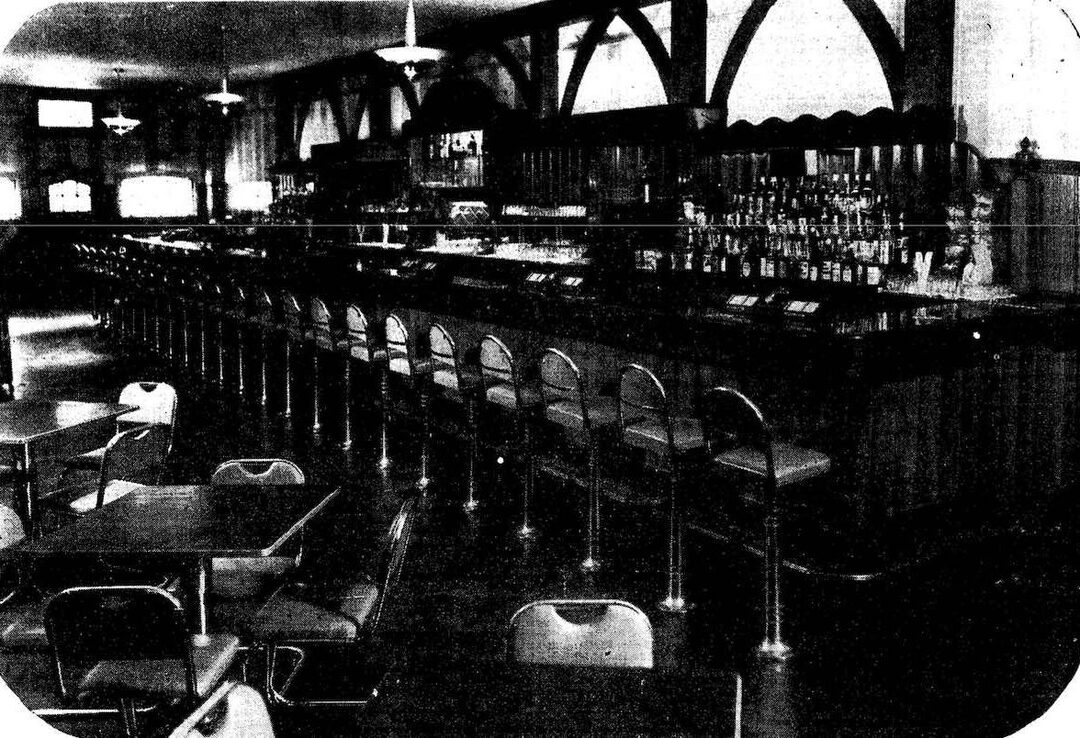

Pierson’s first noteworthy business venture followed the repeal of Prohibition. In 1934 he and Rodger Price, who would become his partner in numerous business ventures, opened the Log Cabin Grill at 2290 East 55th Street. The Log Cabin, styled in the manner of a “swanky hunting lodge,” became one of the most popular establishments in the heart of what many called Cleveland’s Harlem. Along with the Majestic Hotel across the street, the Log Cabin appeared in the Negro Motorists’ Green Book and attracted visiting celebrities such as Duke Ellington and Joe Louis.

With the exception of the Log Cabin, Pierson and Price poured their money into ventures that helped fellow African American entrepreneurs succeed in pursuing their own ambitions. In placing hiring power in African Americans' hands, they went beyond the Future Outlook League's call, "Don't Buy Where You Can't Work." In 1936, the men invested in the dream of Robert H. (Bob) Shauter to own his own drugstore. Shauter, a graduate of the Western Reserve University School of Pharmacy, had worked as a soda clerk in white-owned pharmacies but now had the opportunity to use his degree in his own drugstore, Shauter Drugs, at 9208 Cedar Avenue. When he was denied the opportunity in the early 1940s to open another pharmacy in the Reserve Building at Woodland and East 55th, Shauter turned to Call & Post publisher W. O. Walker for help. Walker decided to buy the Reserve Building to create a space where Black businesses and professional offices would not be sealed out on account of race. But Walker needed investors, and few in the Black community had significant capital. Two exceptions were Pierson and Mason, who joined him in forming the Woodland-55th Corporation, which purchased the Reserve Building and the Leiden Drug Co. inside it in 1943, in turn enabling Shauter to expand his business, which became Cleveland’s first Black-owned drugstore chain.

Indeed, Pierson situated himself as a facilitator of pioneering businesses. His financial support solved the problem of Black bowling leagues’ difficulty in gaining access to lanes in white-owned alleys. Piggybacking on Elmer Reed’s founding of the National Bowling Association, an umbrella for Black leagues, in 1939, Pierson and Price helped Reed start a ten-lane venue called United Recreation at 8217 Cedar Avenue in 1941. United Recreation was reputedly the first Black-owned bowling alley in the United States. Another pioneering African American business that Pierson supported was Sears Brothers Jewelry and Watchmaking School, which had been denied a renewal of its lease in the Prospect Fourth Building in downtown. Pierson and his associates welcomed John and Burl Sears in the Reserve Building in 1945, aiding what was likely the nation’s largest Black watchmaking school.

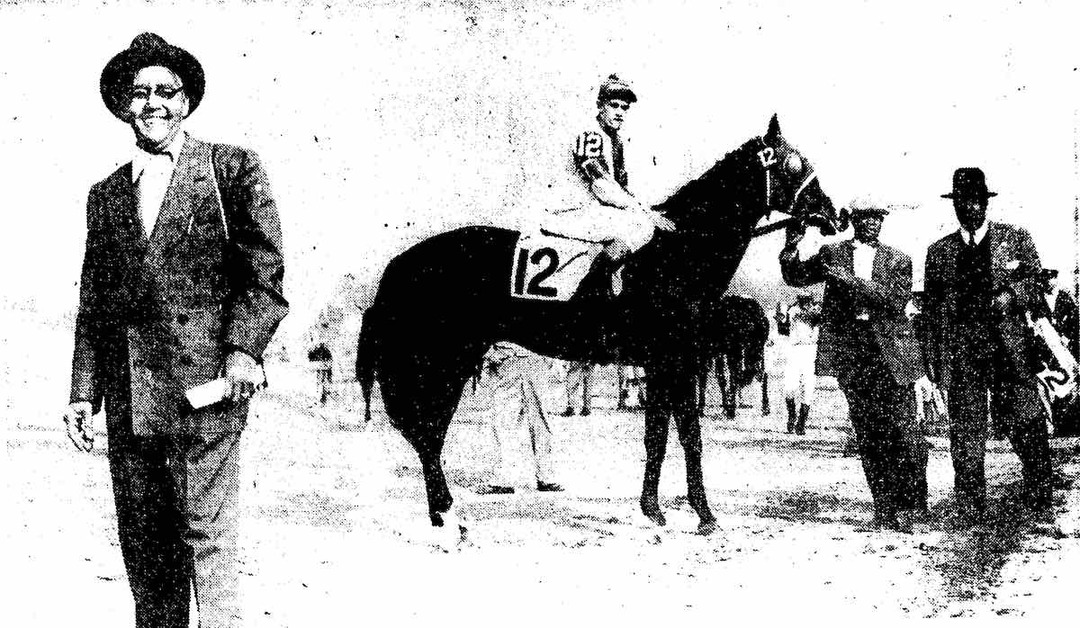

As he invested in Black enterprises, Pierson enjoyed growing prosperity. After years of living in a tiny tenement near Cedar and East 36th, he bought a sizable home in 1939 at 2304 East 89th Street and became a generous supporter of nearby Karamu House, an interracial arts-focused settlement. He also burnished his reputation as a sportsman by owning thoroughbred horses stabled at Thistledown. By 1943, Pierson purchased a tile-roofed brick mansion at the fork of East Boulevard and East 98th Street in the Glenville neighborhood. In doing so, he was in the vanguard of the emergence of East Boulevard as the most prestigious residential address in what African Americans came to call the “Gold Coast.” Just as discriminatory lending practices led some African Americans like Pierson and Mason to turn to illicit numbers activities to generate capital, they also sealed off suburbs from Black homeownership, making places like the “Gold Coast” the closest attainable equivalent.

Not every venture Pierson took on enjoyed success. Another wartime investment that might have been his greatest triumph ended up being his biggest failure. Around the same time that he moved to East Boulevard, Pierson committed $100,000 to start what was billed as the nation’s first Black-owned and -operated factory. The idea originated not in Cleveland but in Toledo, where Black attorney Orlando J. Smith had recently failed to advance a vision for such a factory. Undeterred, Smith convinced Pierson, Price, Mason, and another investor to start the American Enterprises garment factory, which he would manage. On December 30, 1943, the factory opened in a building at 1250 Ontario Street, two blocks north of Public Square. With 210 power machines, the plant employed 129 workers, most of them African Americans, and enjoyed a federal war work contract to supply Army coats and other clothing. Despite its promise, the enterprise soon faltered. Even though it had added a significant number of major orders from the private sector, the factory began to struggle to obtain supplies and also suffered from Smith's managerial inexperience and what the owners complained was government officials' “Jim-Crow” refusal to extend loans. By January 1945, the factory was shuttered and the firm in bankruptcy.

After the war, Pierson tailored his longtime advocacy for mentoring and bringing Black entrepreneurs into co-owned business enterprises to the pressing need to create jobs for returning Black servicemen. He argued in 1946 that African Americans with the means should pool their resources, saying, “We’ll never control the business life in our own communities until we buy the buildings in which it is housed.” In 1947 he and Price helped Wendell Bishop, long a porter in the downtown Thom McAn Shoe Co. store, open his own shoe shop in the Reserve Building, a venture jointly owned by Bishop, Pierson, Price, Mason, W. O. Walker, and Frances Shauter (Bob Shauter’s widow). Echoing other Pierson beneficiaries, Bishop Shoes became the city’s first Black-owned shoe retailer. As Pierson told the audience at the testimonial dinner in his honor that same year, “If I had two million dollars I’d solve the economic problems of the Negro in Cleveland with the simple theory that wealth is not the cash you have in the bank but the money you put to work.”

Had Pierson remained in Cleveland and lived longer, he might have been overjoyed to see African Americans succeed in moving into once-exclusionary suburbs but saddened to see how white disinvestment and limited amassing of Black capital combined to hollow out the Cedar-Central neighborhood where he had helped build the pulsing heart of Cleveland’s Black Metropolis. But Pierson moved to Victorville, California, in 1951 after buying an interest in Murray's Dude Ranch (an important Green Book site along Route 66), and he died in 1963. One year after his death, former Log Cabin hostess Ella Mae Ellis bought the business, but it only lasted for seven more years. In 1965, Elmer Reed closed United Recreation after a drop in the popularity of bowling and a failure to get his insurance policy renewed. In 1966, the Woodland-55th Corporation sold the Reserve Building—for twenty-three years the city’s largest Black commercial and office building but now struggling—for a gas station. Likewise, Shauter Drugs' one remaining store closed in the early 1970s.

Although today there is no physical trace of Willie Pierson’s business empire, the houses where he lived as he rose toward the zenith of his entrepreneurial and philanthropic activity are still standing. Today the long line of grand homes on East Boulevard is, to many passersby, merely an attractive backdrop to the Cleveland Cultural Gardens, but the street’s houses also embody the legacy of the World War II years, when influential African Americans like Willie Pierson were pioneers of the emerging “Gold Coast.”

Images