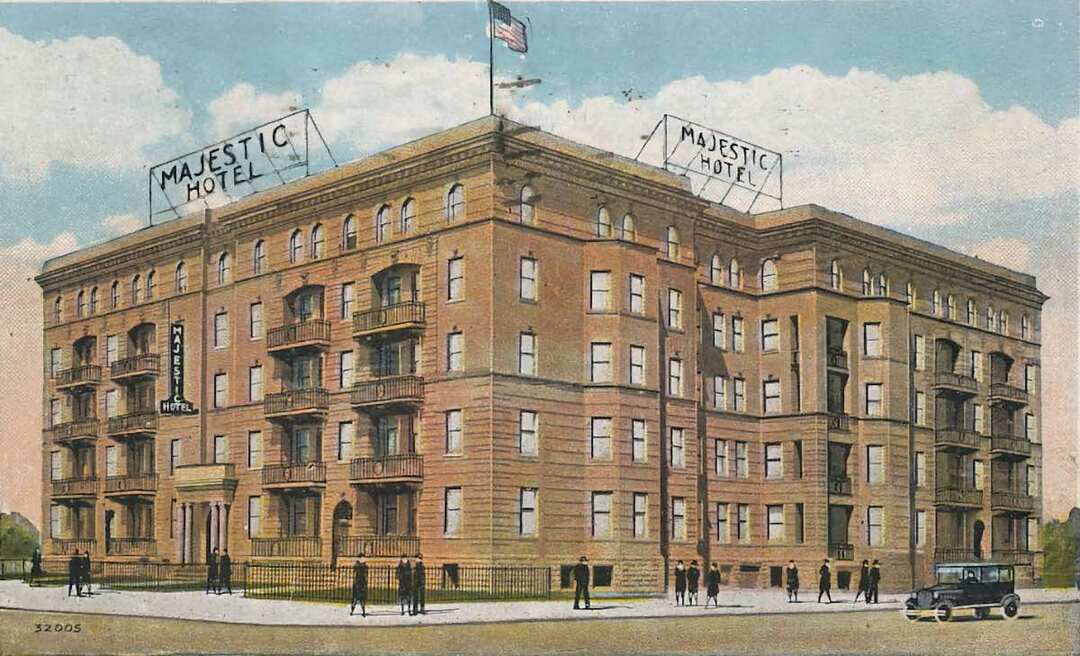

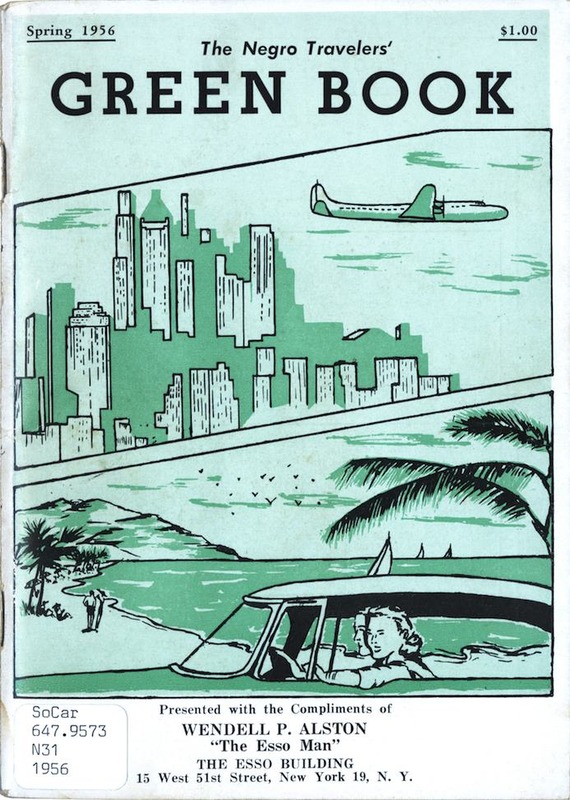

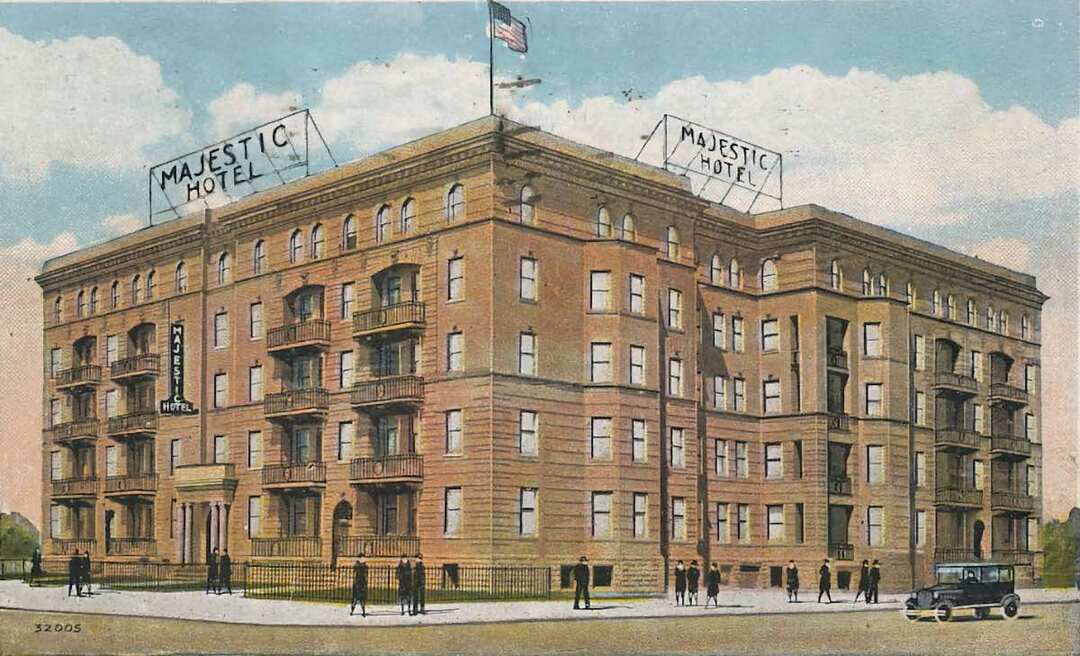

Opened in 1902 as a five-story, 250-room residential hotel known as the Majestic Apartments, the Majestic Hotel emerged after the Great Migration as Cleveland's primary African American hotel, a role it played until integration eased the need for hotels catering primarily to a black clientele. From the mid-1920s to mid-1940s it was owned by Josef Weiss, who was Jewish of Hungarian descent, and managed by an African American man named Ted Witbeck. The imposing brick structure on the corner of East 55th Street and Central Avenue in the heart of the city's Cedar-Central neighborhood provided African Americans with a quality place to stay on a visit or to call home. Although the Majestic was listed as apartments in the city directory from 1907 to 1929, its primary function became that of a hotel, and it was the largest Cleveland hostelry listed perennially in the Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide for Black motorists during the Jim Crow era. Not only did the Majestic provide a place for Blacks to stay, it gave them a place to eat, relax, and enjoy musical entertainment free from discrimination.

As early as 1931 the Majestic Hotel had a jazz club originally named the Furnace Room. There, one would find the owners and operators of other local clubs along with musicians who had finished their night's work at other establishments. Patrons enjoyed entertainment from various crooners, dancers and even an accordion player while enjoying the house specialty of barbecue and spare ribs. In 1934 "Mammy" Louise Brooks served New Orleans Creole fare in the Majestic Grill, which also operated inside the Majestic Hotel until it changed hands in 1936 and became Sadie's.

In 1934 the Furnace Room changed its name to the Heat Wave. Once the Heat Wave closed three years later, the spot within the hotel it vacated did not stay empty for long. By the end of September 1938 a new hot spot emerged at the location. Elmer Waxman's Ubangi Club enjoyed a very lively first week of existence according to the Cleveland Plain Dealer. After only a short run, the Ubangi Club joined the ranks of the Furnace Room and the Heat Wave in closing its doors for good. However, the next club to emerge from the location within the Majestic would enjoy more fame than any of its predecessors. The new club emerged near the end of World War II after Weiss sold the hotel to Black investors led by former Sohio gasoline station franchisee Alonzo G. Wright.

While the Majestic may have been a Black hotel located in a largely African American section of Cleveland, the audiences drawn to the hotel's Rose Room Cocktail Lounge in the 1950s were anything but segregated. Indeed, the Majestic and the Log Cabin across the street, were fixtures in the "Black and Tan" scene in Cleveland's version of Harlem. The largest attractions for jazz lovers, according to jazz historian Joe Mosbrook, were "Blue Monday" parties, which featured pianist Duke Jenkins and his band, along with many other jazzmen. These jam sessions made the Rose Room a preeminent venue through the 1950s.

Although Wright was committed to running a thoroughly modern and fashionable hotel and poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into updates in the mid-1940s and again in the late 1950s, like countless Black-owned hotels across the nation, the Majestic lost its reason for being as Jim Crow practices receded. When it reported on May 27, 1967, on the impending demolition of the Majestic to build the Goodwill Industries Rehabilitation Center, the Call and Post, Cleveland's leading Black newspaper, took a bittersweet tone. Observing that the new center would be "a tremendous community development in a slum area," it also concluded, "With the Majestic goes the sounds of music, the voices of the great, and a bright era of Negro community life."

Audio

Images