Anthony J. Celebrezze Federal Building

Federal Modernism Comes to Cleveland

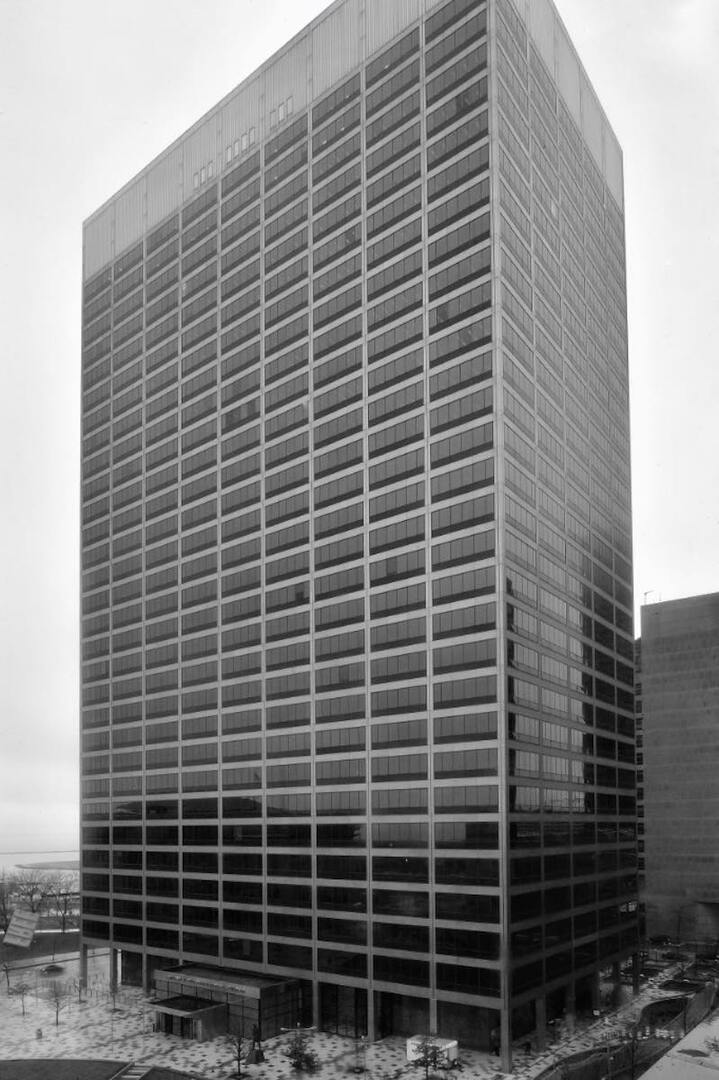

When the federal government began planning its new building as part of the Erieview Plan, it departed from I. M. Pei’s original vision and chose a stunning new design that drew from the latest in Modernist thought. Forty years later, that building was showing its age and required a dramatic intervention. The solution was an innovative facade overclad system that changed the building’s appearance but maintained its original purpose and function.

The 1960s were a very active period for the construction of federal buildings in cities across the country, and Cleveland was no exception. As early as 1957, area members of Congress began pushing for the construction of a centrally located downtown federal office building that would consolidate federal services in the city. The site of the building was determined in 1960 as an integral part of the Erieview Urban Renewal Project in downtown Cleveland. This large scale, multi-phased urban planning project was led by renowned architecture firm I. M. Pei and Associates.

Pei’s 1960 master plan for the Erieview development included a mix of high- and low-rise commercial and residential buildings with more than fifty percent of the land left open for parks and malls. The plan was designed to be completed in two phases; a western area of 96 acres to be designated for primarily commercial use and an eastern area of 67 acres to be designated for residential buildings. The focal point, at the center of the development, was a forty-story office tower. Completed in 1964 and dubbed the Erieview Tower, this was the first part of the Erieview plan to be built. A new six-story federal building that was to occupy an entire city block was also a key part of Pei’s plan. In preparation for the Erieview redevelopment, more than 200 buildings were demolished, including the old Armory that was located on the site of the current Federal Building.

While I. M. Pei developed the master plan for the Erieview development, other architects were brought in to design the individual buildings, including the new federal building. The General Services Administration (GSA), established in 1949 to meet the needs of the growing federal government, selected three local architecture firms to work together on the design of the federal building: Outcalt, Guenther, Rode, Toguchi & Bonebrake; Schafer, Flynn & Associates; and Dalton & Dalton Associates. However, the GSA did not choose a lead designer for the project and left the three firms to resolve the issue. All three firms wanted to lead the project, so a compromise was reached that they would bring in an outside architect to be the lead designer. The firm principals originally thought about bringing in a famous architect to lead the project, but eventually decided to find an architect that worked for one of these significant architects. Peter van Dijk was working for Eero Saarinen and Associates in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, at the time and was selected based on a suggestion by one of Calvin Dalton’s employees. Upon speaking with van Dijk, the principals at the three firms quickly decided he was the right person to lead the design of the Federal Building project.

The design process began in 1961 and continued through 1962. The architectural team was charged with designing a one million square foot federal office building with an “open, flexible, well-planned loft space for offices.” GSA also requested that a two-level parking garage, large cafeteria, and loading dock be included. According to van Dijk, the goal was “to produce a most elegant steel cage. A façade executed with strength and precision. A stressed skin smoothness with machine-like clarity. Good proportion, scale, detail and choice of appropriate materials and colors.”

After careful consideration and study of the site and GSA programmatic requirements, it was decided that the team would design a tall building, which was in direct contradiction to the concept design in Pei’s Erieview Master Plan. The designers’ decision to abandon the Pei design was based on their belief that a tall structure would relate to the existing Terminal Tower and the other buildings being designed in proximity at the time. In their opinion, the large donut-shaped plan did not conform with the “plans for open space and plazas.” They believed a tall building would provide for more space for outdoor plazas, as well as views of the downtown and lake from the upper floor offices. Following their conclusion, the team convinced Pei and GSA that “a tall, slim structure would be more in keeping” with the other high structures planned in the renewal area.

The building was designed as a simple rectangular shape and had the proportions of a golden rectangle. The design also contained a definite base, middle, and top and was intended to utilize simple materials (glass and stainless steel). Furthermore, according to van Dijk, the steel frame of the building became “the basis of the architectural expression of the façade.” The siting was also important to the designers. The building was purposely set back from East Ninth Street to provide room for a plaza at the main entrance and set back even farther on East Sixth Street to create a “garden plaza.”

The design was substantially completed by June 1962 when GSA issued an official press release regarding the new federal building in Cleveland. In the press release, GSA described the thirty-two story building as “an important element in the city’s Erieview Redevelopment Plan” that would “provide the lake-shore metropolis with an imposing landmark.” They also estimated that the building would cost $41.2 million to complete.

The Celebrezze Building was designed during a period of growing public acceptance of Modernist design. The Modernist movement in architecture, which had roots in Europe, began to flourish in the United States following World War II as architects like Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe expanded their influence. As the movement continued to thrive throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s, Modernism became the preferred style of architecture for office buildings across the country. Buildings such as the Seagram Building (1958) in New York City by Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson, as well as the Inland Steel Building (1957) in Chicago, Illinois by Bruce Graham and Walter Netsch of SOM, continued to push the envelope in Modernist design. Significant Modernist skyscrapers in Cleveland include the McDonald Investment Center (1968) by Charles Luckman; the Cleveland Trust Tower/Ameritrust Tower (1971) by Marcel Breuer; Earnest J. Bohn Housing Tower (1972) by William Dorsky Associates; the Diamond Building (1972) by SOM; the Holiday Inn Lakeside (1974) by William Bond; and the Sheraton City Centre Hotel (1975) – now the Crowne Plaza Hotel – by Bialosky and Manders.

The policies of the federal government also reflected the shift toward Modernist design. When John F. Kennedy assumed the presidency in 1961, he found many federal buildings to be lacking in efficient office space and inadequate for modern use. As a result, he requested that an Ad Hoc Committee on Federal Office Space be formed to develop solutions for short- and long-term space needs in federal buildings. In 1962 the committee issued its report, which included the “Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture.” In the “Guiding Principles” the committee recommended new mandates for “high quality architectural designs” for all new federal buildings across the country and developed a three-point system for federal architecture standards. They also encouraged modern principles of architecture through choice words within the standards, such as “contemporary,” “functional,” and “economical.” With the adoption of the new principles, the monotonous architecture of the previous decade gave way to new, innovative, quality design. Although the design of the Celebrezze Building was initiated before the Principles were published, it clearly exemplifies the Principles’ embrace of high-quality modern design.

The building’s expression of structure on the exterior façade follows the design principles of Mies van der Rohe, which can be seen in many of his works, including the Dirksen Federal Courthouse in Chicago completed in 1965. However, unlike Mies who used protruding mullions on his buildings, Peter van Dijk used only contrasting materials – stainless steel and glass – to emphasize the grid of columns and floor plates. According to van Dijk, the solid of the stainless steel and the void of the glass created a solid and void effect that clearly emphasized the building’s skeletal structure. The idea of an exterior skin with no protruding mullions was a concept van Dijk learned in the office of Eero Saarinen from projects such as the General Motors Technical Center in Warren, MI, and Bell Labs in Holmdel, NJ. It continued to be the subject of experimentation with other Saarinen followers, most notably Anthony Lumsden and Cesar Pelli.

In 1965, in the midst of the Civil Rights era, the construction of the new federal building in Cleveland became the subject of protests that received nationwide attention. Led by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), picketers protested discriminatory hiring practices among the predominantly white trades unions involved in the construction of the building. The protest’s leadership also targeted the federal government “for its failure to enforce civil rights laws.” The Erieview plan, of which the federal building was a part, also appears to have strained community relations. Across the country at this time, many cities had undertaken similar projects that resulted in the displacement of their most vulnerable residents and the destruction of their homes, with disproportionate effects being felt by the African American population. In Cleveland, many poor Black residents perceived that the Erieview project, which was located in the heart of the downtown area and treated as a showpiece by politicians and government officials, was diverting badly needed resources from projects in critically underserved east side neighborhoods. This resentment, combined with myriad other factors, burst out into the open the following summer in the Hough Uprisings, an episode of violent unrest comparable to the riots that occurred in Harlem, Watts, and other urban areas during the 1960s.

The Cleveland Federal Building was substantially completed in the fall of 1966 at a cost of $31,968,000 (substantially less than the budgeted $41.2 million) and officially opened in early 1967. The new building housed more than fifty government agencies that had previously been spread out in buildings throughout the city. In 1973, the building was renamed in dedication of Anthony J. Celebrezze, former Mayor of Cleveland, Ohio Congressman, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare in the Kennedy Administration, and U.S. Appeals Court Judge. As mayor, Celebrezze was an early proponent of the Erieview Urban Redevelopment Project and helped in the process of bringing the Federal Building project to realization.

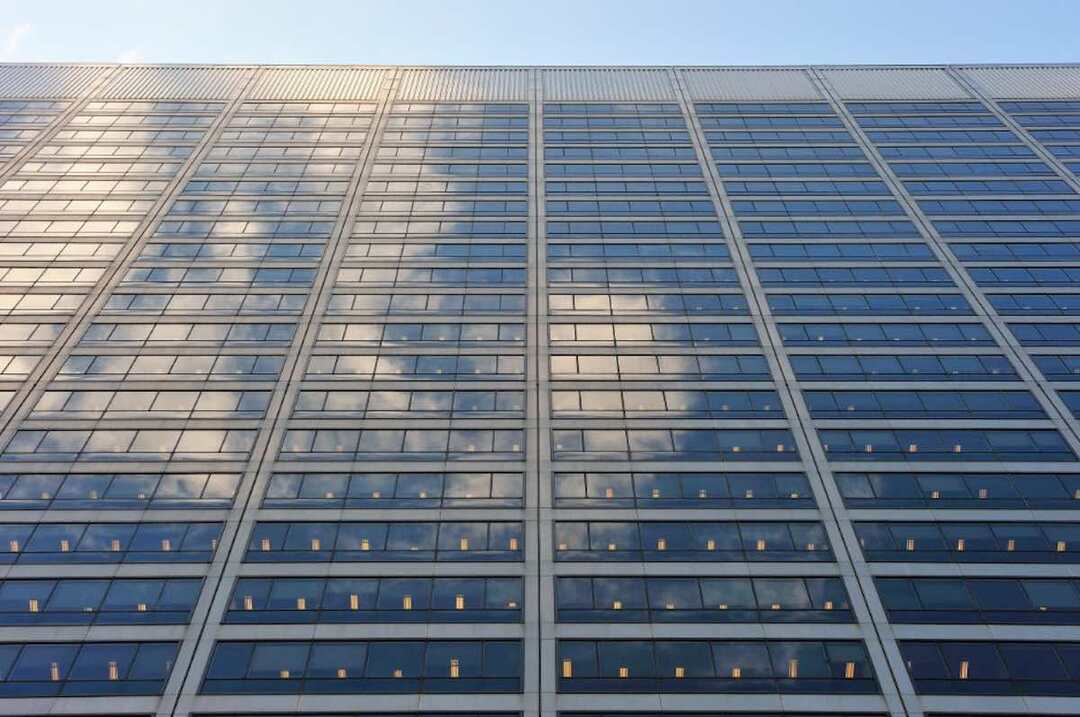

Following its completion, the building underwent relatively few significant alterations until 2009, when GSA utilized funds available through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) to begin a massive intervention addressing the condition of the curtain wall. Flaws in the original detailing and installation, water infiltration, the action of wind forces, and the harsh Cleveland winters had resulted in advanced deterioration on the façade’s various components. Additional assessments found the curtain wall to be strikingly deficient in terms of modern energy efficiency and security standards. Ultimately GSA decided to install a second skin on top of the existing façade, effectively overcladding the original building with an entirely new window wall system.

Pursuing this innovative approach allowed GSA to retain the existing building, thereby avoiding the expense and inefficiency of constructing an entirely new building and relocating the current building’s occupants. Additionally, it allowed the agency to preserve a historic asset. In 2011, the Celebrezze Building was determined eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places for its exceptional local historic and architectural significance. This determination rests on the Celebrezze Building’s distinguished modernist design and its role in the history of the Erieview plan and the development of the modern Cleveland skyline. It also recognizes Peter van Dijk as a master architect. Comparatively unknown at the time that he designed the Celebrezze Building, van Dijk went on to become one of the Cleveland area’s most celebrated designers. Following the Celebrezze Building, he designed the Blossom Music Center (1968) in Cuyahoga Falls. Subsequently, his firm developed a global reputation for expertise in the design of performance venues. A committed preservationist, van Dijk was also a driving force behind the plan to save Cleveland’s Playhouse Square theaters. Recognizing the need to address issues with the original design and construction of the Celebrezze Building, van Dijk supported and participated in the façade renewal project. Peter van Dijk passed away in 2019 at age 90.

Following the completion of the facade overcladding, the Celebrezze Building was identified as a contributor to the Erieview Historic District, which was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2021.

Images

![Central Armory, O.N.G. [Ohio National Guard], Cleveland, Ohio](https://clevelandhistorical.org/files/fullsize/f55aee89077f0098b4d315e7b7d2da22.jpg)