The 1930s signaled the beginnings of a new era for the Cleveland Metropolitan Park System. Under the guidance of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, the Cleveland Metropolitan Park Board constructed three buildings that changed the way the public used and understood Cleveland parks.

Tucked away in the oak-hickory forests of the Cleveland Metroparks Brecksville Reservation, the black walnut doors, American chestnut paneling and Berea sandstone that front the Brecksville Nature Center blend harmoniously into the surrounding wooded landscape. Constructed with regional materials by laborers of the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration, the historic exhibition space is a shrine to its location. Details of the interior and exterior design relay stories of the flowers, trees and animals native to the vicinity. A short path leading to the building extends visitors an invitation to explore, learn, and immerse themselves into the natural world. Opened to the public in June of 1939, the Brecksville Nature Center was one of three trailside museums operated by the Cleveland Metropolitan Park Board in collaboration with the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. The construction of these trailside museums during the 1930s signaled the beginnings of a new era for the Cleveland Metropolitan Park System. Through the efforts and guidance of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, a foundation of educational and research programs emerged that both helped shape the use and provide cultural value to Cleveland's newest public spaces.

The partnership between the Metropolitan Park Board and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History that prompted the establishment of trailside museums grew from the board's efforts to display the benefits of a remote park system to Clevelanders. Through much of the 1920s, the Park Board had been busy both purchasing and pursuing eminent domain on what would amount to nearly 9,000 acres of land; while the property obtained was generally not suited for commercial, residential or agricultural uses, its speedy procurement was critical to keep prices low and prevent land speculation. By plan, the Park Board had devoted very few resources to developing spaces for public use.

With the skeleton of a park system in place, and the renewal of a tax levy up for a vote in 1930, the Park Board shifted the disbursement of over three-quarters of available funds to land improvements in 1928. By making portions of park land physically accessible and developing recreational spaces, the board hoped to garner public approval and interest in the metropolitan park project. There was a small hitch, however. While maintaining small departments for legal needs, draftsmen, accounting, landscape design, police protection, engineering and golf course personnel, the organization had no employees devoted to offering programs or educational services to the public. Additionally, the Cleveland Metropolitan Park Board was limited in its powers to enter into contractual relationships with outside organizations. The board relied on informal arrangements with civic institutions to provide cultural value to the public space. In 1929, the Ohio State Legislature empowered the Park Board to enter into working contracts with non-profit corporations. Collaboration between the board and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History was cemented that year with the designation of Arthur B. Williams as the park system's first naturalist.

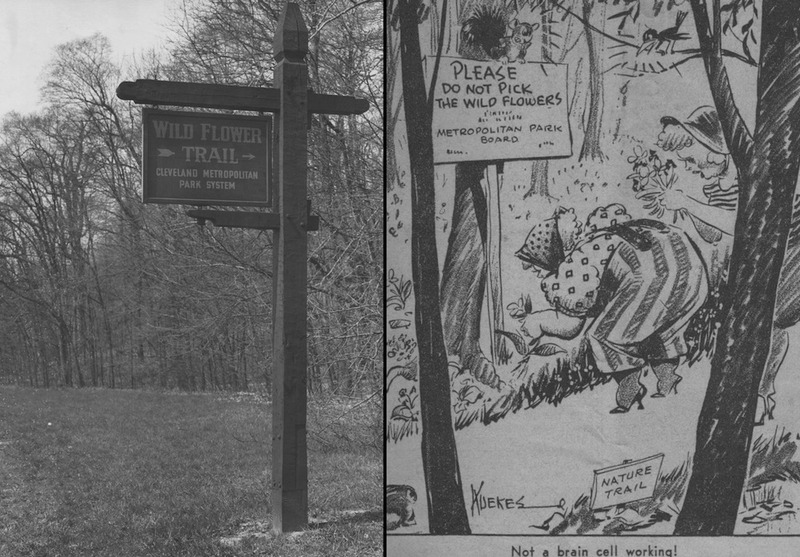

Williams tirelessly worked as a "one-man department" performing extensive field research of the park grounds, creating publications for professional and general consumption, and integrating his findings into interpretive programs for the public. Emulating a trailside museum model popularized at Bear Mountain State Park in New York, a small rustic cabin was opened under Williams' direction in the North Chagrin Reservation during the summer of 1931. Conceived as a tool to get people into the park, the North Chagrin Trailside Museum was embedded within the woods and acted as an adjunct to a nearby educational nature trail previously established by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Both the museum and trail were designed to convey an educational narrative of the beech maple climax forest to park goers.

Visitors to the museum were instructed by an assortment of hands-on exhibits pertaining to the natural history of the region - both inanimate and otherwise. The most acclaimed attraction was an array of tame or baby animals, which included black snakes, skunks, opossums, woodchucks, turtles and owls. Whether it be Pete the raccoon, a collection of arrowheads or cross sections of trees, all exhibited objects and animals were common to the area. Each was chosen to help inform visitors in their jaunts along the park trails. With Williams generally on hand to answer questions, or to summon crows to perch on his arm in anticipation of food, a visit to the museum was designed as an exercise in non-compulsory education. Weekly informal talks and guided nature trail hikes were offered for those wanting more.

The exhibits, events and presentations offered by both Williams and Cleveland Museum of Natural History staff at the trailside museum proved successful in attracting an enthusiastic public. By 1935, the informal outdoor lectures performed in a small clearing between the cabin and nature trail regularly packed in over 140 eager, inquisitive visitors. Over 34,000 persons had visited the North Chagrin Trailside Museum the prior year, and the educational nature trails continued to attract throngs of park patrons. With the immediate and apparent success of the trailside model in North Chagrin Reservation, plans had long since been concocted to build similar centers along educational nature trails in other parks. Limitations in staff and funding due to the looming economic depression thwarted these efforts.

With the assistance of federal funding and work relief projects, additional trailside museums were erected in the Rocky River and Brecksville Reservations during the mid 1930s. Each mirrored the characteristics of the North Chagrin museum: small rustic cabins were set into the woods adjoining educational nature trails, and were devoted to telling the story of the unique environments in which they sat. In Rocky River, construction of the museum was supervised by the Metropolitan Park Board's Landscape Department as a Works Projects Administration project. The cabin premiered in the fall of 1935, and was opened to the public the following summer. Under the guise of eyeballing resident toads, salamanders and pollywogs, programming and exhibits interpreted the habitat of the northern Ohio flood plain. Situated just a short walk from streetcars, the Rocky River museum soon matched the attendance of its North Chagrin counterpart.

The location of the third Trailside Museum was chosen to depict the oak hickory forests of the Brecksville Reservation. While work on the building was started by the Civilian Conservation Corps, its completion - as well as the fine craftsmanship - can be attributed to skilled laborers employed through the Works Progress Administration. Accompanying the opening of the Brecksville museum in 1939, the North Chagrin cabin was also enlarged and remodeled as a Works Project Administration project. A fourth Trailside Museum was opened in 1943 by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History at Gordon Park to interpret the habitat of Lake Erie. This collaboration with the City of Cleveland proved short-lived, however; the building became inaccessible and was abandoned during the construction of the Memorial Shoreway, but was eventually revamped as the Cleveland Aquarium.

The three Trailside Museums within the park system continued to offer informal lectures, guided nature walks, and a variety of rotating and permanent exhibits. Guarded by the forests from the sights and sounds of urban life, these small buildings acted as a hub for interaction between the public and representatives of the Cleveland Metropolitan Park District. The Park Board eventually took over the reins of managing the museums in 1954 following the creation of its own educational department. Having consistently provided interpretive programming and hands-on educational opportunities at trailside museums for a quarter century, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History helped change the way the public perceived and used parks in Cleveland.

Building upon the Natural History Museum's legacy, the Metropolitan Park District continued to expand educational programming within the park system. New, modernized nature centers were built to house public events and exhibitions, as well as to provide amenities to visitors. While both the North Chagrin and Rocky River Trailside Museums were eventually destroyed by fire, the museum in Brecksville Reservation was revamped as the Brecksville Nature Center. The structure, dating back to the days of the Works Progress Administration, still stands as a reminder of the Park Board's earliest efforts to both engage with and provide educational programming to the public.

Audio

Images