The 9, originally called Cleveland Trust Tower and then Ameritrust Tower, is the only skyscraper designed by one of the most eminent Modernist architects of the 20th century, Marcel Breuer. But like a number of projects Breuer designed in his career, this Brutalist tower did not win universal praise and was nearly destroyed in the early 2000s.

Marcel Breuer was a Bauhaus-trained architect and furniture designer. A native of Hungary and a protege of the eminent Modernist architect Walter Gropius, Breuer earned a reputation for designing furniture and tubular steel chairs such as the Model B3 or Wassily Chair in the 1920s. In 1938 he joined Gropius on the faculty at Harvard's Graduate School of Design. For the next three years, Breuer and Gropius collaborated on several residential designs, including Aluminum City Terrace, an International Style defense housing project near Pittsburgh in 1941. The 240-unit "ultra-utilitarian" compound of prefabricated multifamily and semi-detached dwellings immediately drew "intense antagonism from surrounding economically well-off private residential property owners" who decried the project's design. It would not be the last time Breuer's designs produced strong feelings.

In the 1950s, Breuer continued in domestic architecture but also moved into institutional building design, notably in his UNESCO headquarters and I.B.M. Research Center in France. He went on to design the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 1966, which earned him accolades, but when he produced a design for the proposed FDR Memorial that same year in Washington, D.C., the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts rejected his creation as a "disrespectful" "pop art sculpture." Breuer found a better reception with his design of the Department of HUD headquarters in the Southwest Washington, D.C. urban renewal project, and he enjoyed commissions for a number of laboratories, university and museum buildings, including the Education Wing at the Cleveland Museum of Art, completed in 1971.

The latter commission, received in 1967, led Cleveland Trust Company to turn to Breuer to steer the expansion of its downtown offices at Euclid and East 9th Street, where George B. Post's early-1900s rotunda was too small for the bank's needs. Breuer was no stranger to Modernist additions to historic buildings. He had recently designed a proposed pair of skyscrapers to rise above Manhattan's Grand Central Terminal, but the project foundered because it underestimated the groundswell of commitment to historic preservation among New Yorkers who were still reeling from the loss of the grand Penn Station.

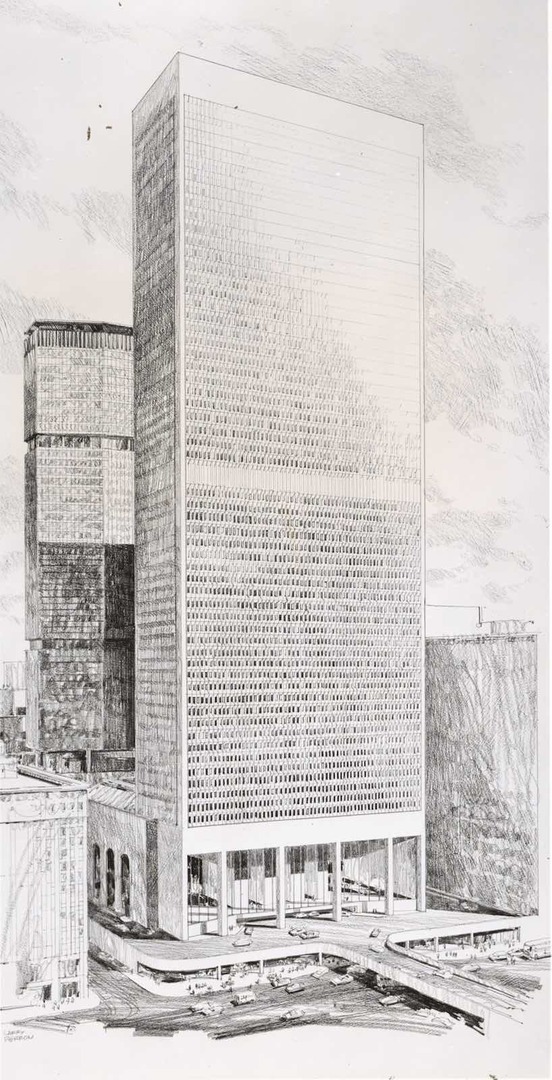

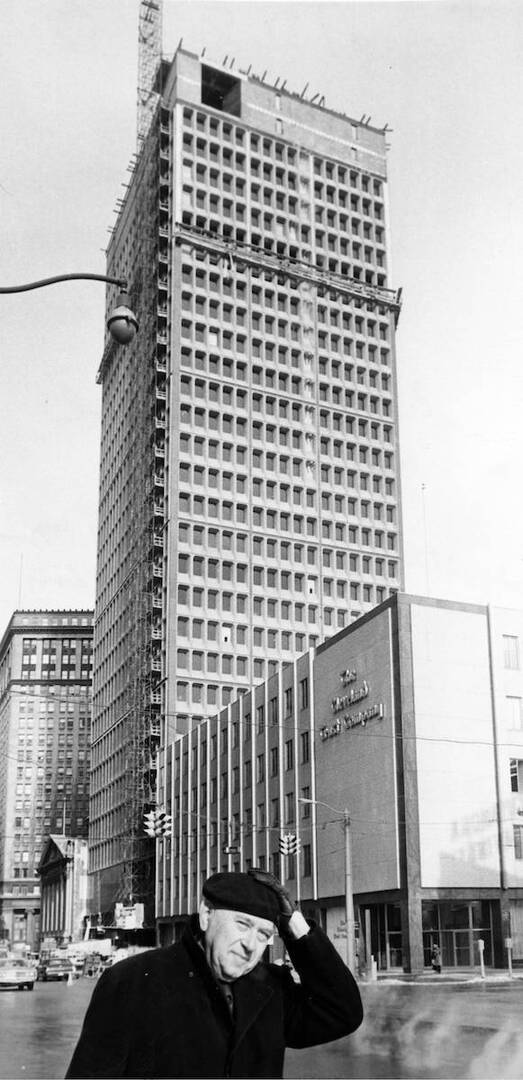

In Cleveland, Breuer planned twin 29-story towers that together would frame the old rotunda with frontage on Euclid and East 9th. Elements of the building's design evoked Breuer's HUD headquarters. The first tower, clad in black granite with cast concrete window frames, was completed on the East 9th side in 1971. Bank president George Karch was quick to assert that it reflected Cleveland Trust's dissent from the prevailing "gloomy predictions" about downtown's future. However, by that time, the second tower's expected construction was not expected to start before 1975. Not only was the second tower ultimately not built, its twin and the rotunda were abandoned in 1996 after Ameritrust (as Cleveland Trust had renamed itself in 1971) merged in 1991 with Society for Savings, which had recently invested in expanding its footprint on Public Square, leading to the construction of the Society Center. Society and KeyCorp, which acquired it three years later, had no need for the old Cleveland Trust complex.

The tower sat empty for nearly a decade before Cuyahoga County purchased it in 2005. County commissioners tried to convince the public to support demolishing it for a new county administration center because it was purportedly beyond saving. The threat of demolition hung over the tower for several years, stimulating considerable efforts to highlight the building's many merits, including its build quality, the renown of its architect, the fact that this was Breuer's only skyscraper.

After the county commissioners' failure to assemble the needing financing for a new county complex and their becoming embroiled in scandal, the Geis Companies, a Northeast Ohio real estate development firm, stepped in and offered to purchase the skyscraper and rotunda and undertake their adaptive reuse. Completed in 2015, the rotunda opened as a distinctive Heinen's supermarket, while the tower became the 156-room Metropolitan Hotel and 105 apartments, and the adjacent Swetland Building contained part of Heinen's on the first floor and more apartments on upper floors. The project did much to reenliven a forlorn corner of downtown and ensured that Cleveland did not destroy what was possibly the boldest expresssion of one of the 20th century's greatest Modernist designers.

Audio

Images