The ornithology collections of the Cleveland Zoo and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History trace their origins partly to the backyard zoo and aviary that banker and investor Kenyon V. Painter cobbled together on his Cleveland Heights estate from his far-flung travels around the world.

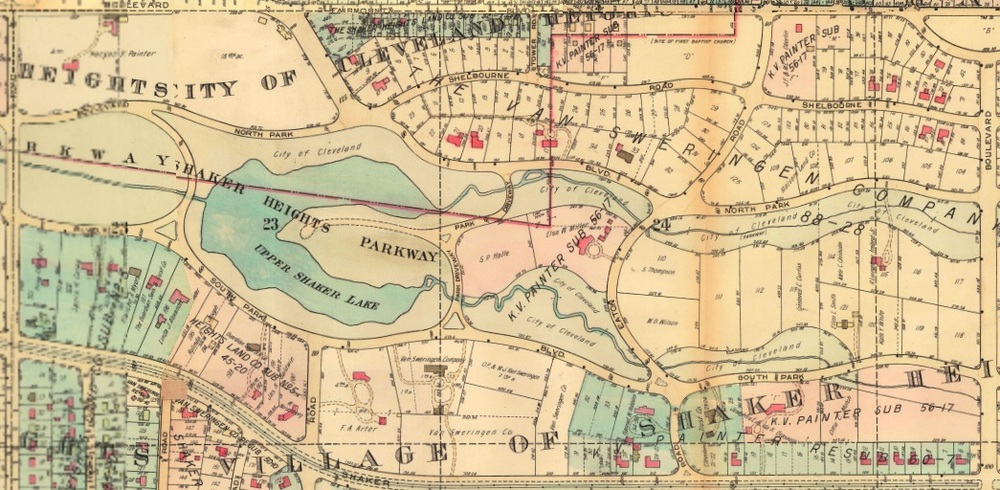

Kenyon V. Painter (1867 - 1940) grew up on the 25th block of Euclid Avenue. His father, John Vickers Painter, a wealthy banker, railroad man and associate of John D. Rockefeller, purchased 8.5 acres in Cleveland Heights and hired Frank Skeel to design a summer home for his family. After the elder Painter’s untimely death in 1903, his wife and son Kenyon continued construction. The 65-room Jacobean-style house, completed in 1905, was situated on a property covering more than 50 acres. After serving as a summer refuge for more than a decade, the estate became the family's permanent home in 1915. Mr. Painter followed his father into a successful banking career with Cleveland’s Union Trust Company.

Painter was a product of the Gilded Age. His wealth and stature afforded him many luxuries and hobbies, including expensive automobiles, big game hunting in Africa, and flirtations as an inventor (Painter sought a patent for a novel golf ball design in 1903). As an automobile enthusiast, Kenyon received one of Cleveland’s earliest speeding tickets for traveling along Rockefeller Parkway in 1901 at twice the 10 mph limit. In 1903, he “ran over” a young boy at a downtown intersection, breaking the boy’s collarbone and shoulder. Painter’s chauffeur took the boy to Lakeside hospital. The police arrested Kenyon, who posted bond, claiming the boy ran out in front of his car. It is plausible that Painter's social status helped his case. Among his well-connected friends was former President of the United States Theodore Roosevelt, with whom he shared safari resources during his frequent hunting trips to the African continent.

Despite his seemingly freewheeling nature, Kenyon Painter also sought to establish familial roots. He married Mary Chisholm in 1889. They had one daughter who died in 1894. Mary died in 1901, and soon after, Painter married Maud Wyeth. They would have four children but again suffer the loss of a daughter in 1921 – somewhat ironically, in an automobile accident.

Painter's globetrotting safaris often mixed leisure with business. Kenyon and Maud honeymooned for three months on a safari in German East Africa, one of 31 extended hunting trips between 1907 and the 1930s. During these trips, Painter established investments near Arusha, Tanganyika, where he developed an 11,000-acre coffee estate, and built Arusha’s first post office, church, hospital, hotel, and coffee research facility with an $11 million investment.

Kenyon Painter's passion for wild animal trophies and specimens manifested itself on his Cleveland Heights estate grounds. In 1928, Tudor details were added to the mansion in addition to a garage, a stable, zoo and aviary, playhouse, and a small house for Painter's secretary. His trophy room surpassed any other and his two aviary facilities were filled with specimens personally secured when visiting foreign countries. The New York Zoological Society documented his bird collection in its September 1913 bulletin. The writer lauded “Painter’s aviaries as excellent examples of what can be done in private enterprise… Everything possible was done for the comfort of the birds…” He went on to document the birds in the collection, noting it “is cared for by a very intelligent Italian woman, and the uniformly perfect condition of her charges attests her skill in handling them.” In time, Painter would donate birds to the Cleveland Natural History Museum and to Cleveland Brookside Zoo to support the ornithology collections.

Like many fortunate sons, Painter may have taken for granted the privilege that his father's fortune afforded him. In 1935, he was involved in a notable financial fiasco. As the director and major stockholder of the Union Trust Bank, Painter borrowed nearly $3 million and was unable to pay it back, causing the bank to fail. He was sued and sentenced to prison in Columbus but fell ill and was hospitalized. Ohio Governor Davey pardoned the conviction and Painter returned to the estate where he lived quietly until his death in 1940.

Painter's life was marked by adventure and intrigue, loss and disgrace, excessive wealth and financial disaster. Philanthropy is perhaps his most lasting legacy. Painter's donations to the Natural History Museum and Cleveland Zoo helped both organizations start their ornithology collections with contributions following his early safaris. The Natural History Museum documents letters of thanks for the donation of a Turaco and parrot in 1930 and cites catalogs of his earlier donations. The zoo indicated Painter's donations included a Japanese robin, two black-headed parrots, two Indian geese, an Australian parakeet, two cranes, four Singapore doves, a silver pheasant, a South African golden oriole, and a South African black-breasted dove. Upon the sale of his estate in 1942, Painter's widow, Maud, donated his remaining aviary of 500 birds to the Cleveland Zoo.

Likewise, the sprawling Painter Estate found a new life. Shortly after Kenyon Painter's death, the Ursuline Academy (a school for girls at East 55th Street and Scovill Avenue in Cleveland since 1893) was in need of more space. On February 21, 1942, Maud Painter agreed to sell her Cleveland Heights mansion and property to the Ursuline Sisters for use as an educational facility. The sisters modified the house for classrooms and a library and used auxiliary buildings for related school facilities, including a gymnasium in the main trophy room where Kenyon had once kept his prized specimens. In 1943, they renovated the Aviary building. By 1964, the sisters built a new school building on the property with classroom space for 540 students, a new gymnasium, dining room, chapel, and administrative offices. The Aviary and Trophy Rooms were converted to house the Fine Arts Department. As the school progressed through the 20th century, additional facilities were added on the grounds and the mansion was used to house the nuns and for administrative offices and functions.

In 1979, the Painter Estate was declared a Cleveland Heights Landmark. It also has been featured on the Heights Community Congress’s “Heights Heritage Tour.” Despite its historic significance, the future of the Painter Estate is unclear. By the turn of the 21st century, studies were commissioned to explore options to renovate and utilize the mansion for schooling functions once again. Cost estimates to maintain or convert the mansion space were prohibitive for the nuns. They sold the property and building to Beaumont School in July 2009 and some administrative functions remained in Painter’s house. By 2017-18, Beaumont School administrators and directors removed staff from the building for safety and maintenance concerns and subsequently adopted a plan to demolish the mansion and use the land for athletic facilities. The City of Cleveland Heights has resisted action on the plan, and the ‘mothballed’ building stands today.

Images