Jim's Steak House

On the one hand, it was a bucolic, glass-walled, red-meat Mecca with unobstructed water and city views. On the other hand, both the Cuyahoga River and the City of Cleveland were increasingly dark, smelly and bereft of life. Moreover, travel to and from the restaurant was the kind of creepy, nail-biting experience that only a golem could love: a dim and bumpy ride to an isolated peninsula in the Flats.

Such were the contradictions that, by the middle of the 20th Century, defined Jim’s Steak House. But through most of the restaurant’s life, negatives and setbacks hardly seemed to matter. In fact, in the eight years after its founding in 1930—when Cleveland and the Flats were still bustling—Jim’s Steak House served 280,000 steaks. Untold thousands of quality meals would follow until the eatery finally shut down in 1997.

“Jim” was James Kerkles, a Greek immigrant who arrived in the US in 1905. In 1930 he and his wife Hilda opened their restaurant on West 9th Street. They relocated to the Flats’ famous Collision Bend within a year, occupying a building that previously housed the Lumberman’s Club restaurant. (Ironically, the Lumberman’s Club had just moved downtown.) Jim and Hilda’s timing was ideal: The Eagle Street Bridge had just opened across the street and visitors would be able to view the newly completed Terminal Tower across the river. But like the two arteries leading to Jim’s (Scranton and Carter Roads) there were plenty of potholes ahead. On June 15, 1939, Kerkles died at the age of 53. From that point on, Jim’s Steak House would, in effect, be Hilda’s Steak House. The following year, the decision was made to make Collision Bend more navigable, which necessitated the restaurant’s demolition.

The new Jim’s opened within two years, only a few dozen feet southwest of the previous location. Accordingly, its address jumped from 1782 Scranton to 1800 Scranton. Such progress! Hilda later remarried and by the end of World War II she and her nephew Ray Rockey were the meat and potatoes of Jim’s Steak House. Hilda managed the money—keeping the restaurant in the black while hiring only white women as waitresses and clothing them in all-white uniforms. Ray handled most of the day-to-day operations, working constantly and living in an apartment above the restaurant. "It's like taking care of a baby that never grows up," Rockey once said.

The formula worked: Blue collars from the Flats, white collars from downtown and wet-collars from the river and nearby fire station filled Jim’s during the day. At night couples, partiers and glitterati swilled Johnny Walker Black ($.75 in 1950) and devoured strip steaks ($4.50 in 1950). The Goodtime ferried diners to and from Cleveland Indians games. Heavy food was de rigueur: red meat, no soup, no salad (except head lettuce) and no vegetables except onions (which were fried). 300 to 400 people was a decent day’s attendance.

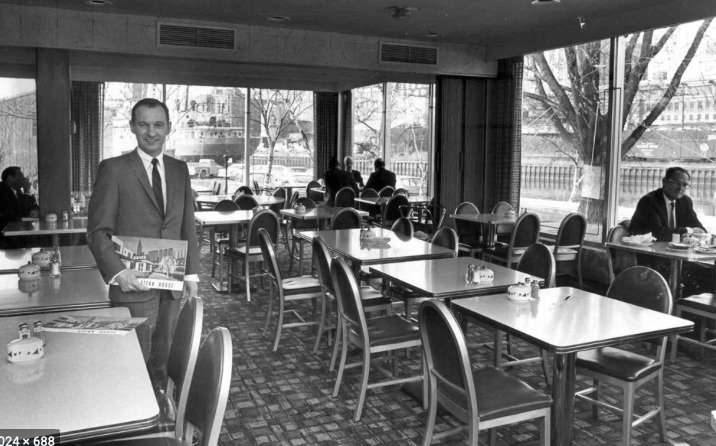

In the 1960s the building was remodeled, with giant glass windows offering diners a more panoramic view of the city. Weeping willows and birch trees (planted over the years by Hilda) added to the ambience.

Hilda died in 1974 at age 75 and Ray Rockey assumed full control of what was still a thriving operation. But like graffiti emblazoned across the Flats, the writing was on the wall, and a lot of it spelled “competition.” By the late 1970s myriad entertainment options had popped up on both the East and West Banks. The Flats had always had niche bars and eateries (Pirates Alley, Otto’s Grotto, Harbor Inn, Flat Iron Café), but this was different: The area actually was becoming a destination of choice—not just for pubby drinking and dining joints like Fagan’s and the Cleveland Crate and Trucking Company but for high-end eateries such as the Watermark and Sammy’s.

The worst body blow landed in 1991 when the city closed the Eagle Avenue lift bridge for a two-year renovation. In a lawsuit, Ray Rockey claimed that, as a result, Jim’s lost 65 percent of its business. Rockey died in 1995 at the age of 71, three years before the Ohio State Supreme Court awarded the restaurant $483,000 in compensation. By that time the bridge had reopened (1993) but Jim’s had shut down (1997). The bridge closed for good in 2005. New occupants of the restaurant space—the River House, the Aqua club, the Mega Nightclub—soldiered on until 2011 when the building was demolished.

Readers responded en masse to a May 2020 Cleveland.com article on Jim’s Steak House. Virtually everyone heaped praise on the restaurant. However, the most vivid account may have come from Bruce Tyler in Cleveland Heights who recalled . . . “As restless 9-year-olds, [we] ran out back on the lawn toward the river before the food arrived. We watched in awe as an enormous ore boat negotiated the tight river bend. The water was an unhealthy shade of brown, with some iridescence on the surface, and rising bubbles would stretch a bit before they popped, as if trapped in goo. I thought about this sight last year when we kayaked on the river around the same location and saw blue water, not brown, and saw herons in the shallows. Thank you environmentalists everywhere.”

Images

A Plain Dealer ad from September 8, 1940 offered pieces of the old Jim’s Steak House at bargain prices.