Since the early 1960s, Moreland's community associations have helped guide the implementation and development of nearly every urban renewal and redevelopment project initiated by the City of Shaker Heights in their neighborhood. Learn how and why a group of community activists reshaped their community in pursuit of integration.

Visitors to the Moreland neighborhood in Shaker Heights are greeted with picturesque sights of an idealized inner ring suburban community. Attractive tree lawns line its residential streets, which lead past rows of well-maintained Cleveland Doubles, American Foursquares and Bungalows. City parks and designated recreation grounds are scattered throughout the neighborhood, with vacant lots appearing to receive the same high level of maintenance as their green space counterparts. Commercial and retail buildings stand along the main throughways, with many of the stores consolidated within a highly uniform suburban shopping strip. A stately civic building, now home to the public library, acts as the symbolic center of the neighborhood. The area seems to effortlessly combine the feel of city life with hallmark traits of suburbia. A tradition of intensive municipal planning and management, however, underlies the history of these commercial, residential and public spaces. The civic engagement of Moreland residents proved key to the success of these efforts.

Since the early 1960s, Moreland’s community associations helped formulate, shape and implement nearly every urban renewal and redevelopment project initiated by the City of Shaker Heights in the neighborhood. The Moreland Community Association (MCA), established in the spring of 1962, was the first of these groups. The organization acted as the front line for identifying and publicly addressing perceived threats to community stability, and functioned as an intermediary between local residents and governing organizations. From the minutia of announcing everyday community activities to the tackling of contentious social, religious, economic and political matters, MCA had a hand in nearly every aspect of life in Moreland. Their resume of achievements included helping to guide the development of the Shaker Heights Service Center, Chelton Park, the Sutton Townhouse Development Project and Shaker Towne Center. The association also galvanized public support for urban renewal projects, advocated for street improvements, aided in implementing and educating residents about housing code enforcement, offered funds for housing upkeep to low income residents, precipitated a minor barricade controversy, purchased and rehabilitated vacant homes, published newsletters, sponsored public debates and held street fairs. By consolidating and amplifying the voices of neighborhood activists, MCA offered a platform for select residents to have a say in defining the future of their community.

The establishment of MCA grew from concerns over the impact of integration in the southwestern region of Shaker Heights. A small group of Moreland residents began meeting in the fall of 1961 to discuss what they perceived to be the potential complications and benefits of African American settlement in the neighborhood. Racial tensions had mounted following the emergence of a small African American community in the neighboring community of Ludlow beginning in the mid-1950s. Panic selling ensued, and the garage of an African American resident was bombed in 1956. To further complicate the matter, realtors and banks steered potential white purchasers away from homes in the neighborhood. The Ludlow Community Association, composed of both African American and white residents, was formed in 1957 to quell fears over integration and counteract the institutional forces that discouraged white families from buying houses in the area.

While modeled after the Ludlow Community Association, the community meetings in Moreland were initially only opened to white residents of the neighborhood. The Moreland community was home to a large population of middle- and working-class southern and eastern Europeans and their descendants. The gatherings were meant as a forum for these residents to express concerns over integration, with the goal of dispelling fears and deterring any physical violence against African American community members. The first racially inclusive community meeting of the MCA was held in February, 1962. Nearly 400 residents attended. A statement of purpose was adopted: “It shall be the common goal of the Association to encourage, to develop and to maintain the quality, stability, high standards and community interests of the area, to promote the general welfare of the entire Moreland Community and to achieve these goals through a democratic community open to all races and religions.” Following the drafting and ratification of a constitution during the next few months, the MCA was officially established. A second public meeting held in April also attracted 400 persons. The organization’s message to the surrounding community was simple: Panic was the only thing they had to fear.

Despite efforts to stave off panic selling and block-busting, the neighborhood witnessed an unprecedented rise of homes being placed on the resale market by 1962. MCA received a $9,330 grant from the Cleveland Foundation the following year as seed money to fund its operations. To counteract the dissuasion of white families from purchasing homes in the neighborhood by banks and realtors, the community association immediately formed a real estate committee. A listing service was developed to bring together home buyers and sellers, and marked the organization’s first endeavor to proactively attract white residents to rent and buy homes in Moreland. Early efforts to stabilize the community also focused on pressuring the City of Shaker Heights to enforce housing code violations. The City was urged to acquire and demolish homes deemed unsuitable for rehabilitation, thereby increasing the visual desirability of the community while decreasing its population.

Moreland’s community activists quickly forged an alliance with the City of Shaker Heights through their work with School and Recreation Boards, the Mayor and City Council. As noted in a 1966 newsletter, MCA enlisted municipal help to “maintain a good neighborhood —clean, attractive, convenient, served by good schools, good municipal services, good recreational facilities, and good business establishment.” The underlying objective of the association’s efforts was to create a stable, attractive and integrated neighborhood. While not presuming “to define by numerical ratio the idea of ‘racial balance,’” MCA advocated for a “neighborhood in which people of many racial, religious, and ethnic groups can live in fellowship and mutual trust.”

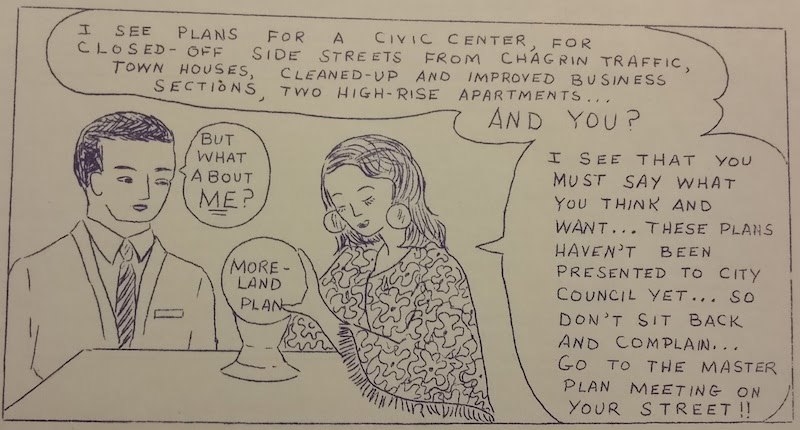

The African American community in Moreland continued to grow throughout the 1960s, facilitated by the increased number of homes placed on the resale market. While the integrated community association eased neighborhood tensions during a time of rapid racial transition, its successes in attracting new white home owners to the area were limited. By the mid-1960s, MCA shifted its emphasis to advocating for large-scale urban renewal projects. A task force, composed in part by Moreland residents and representatives of the City, recommended the development of a master plan for the community in 1966. These efforts culminated in the Styche-Hisaka Plan, an ambitious locally funded urban renewal project that focused on the redevelopment of Shaker Heights’ southern neighborhoods. Plans for Moreland included the revitalization of its commercial district, street improvements and the removal of older, high-density housing stock. A civic center, townhouses, park spaces and service center were proposed to replace many residential homes. While the civic center was never realized due to objections by the Moreland community, homes would be demolished to make room for the Shaker Heights Service Center and a park-townhouse development.

Lateral efforts to renew housing in Moreland were initiated by MCA beginning in 1967. The Shaker Foundation was established by the association to purchase and rehabilitate rundown houses. Properties were then rented or placed on the real estate market for sale. Loans with below-market interest rates were offered by the foundation to entice potential buyers. The community group was also represented in the Shaker Heights Housing Office, which hired one member of the Moreland, Ludlow, Lomond and Sussex community associations to act as housing coordinators. As an arm of the municipal government, the Housing Office’s committee worked to attract white homeowners into the southern region of Shaker Heights and combat practices by realtors and banks that discouraged neighborhood integration. Cooperative work between MCA and the City extended to pursuing private-sector investment for a $2 million revitalization of the Chagrin-Lee-Avalon shopping center in 1969.

By focusing efforts on these City-sponsored urban renewal efforts, the work of MCA became intertwined with municipal government operations. The association continued operating as a community group into the 1990s, but efforts to promote both integration and urban renewal projects were increasingly pursued by members through their involvement with City boards and committees. These official mechanisms for promoting the stabilization of Moreland emerged during MCA’s first decade of existence, and were largely a response to work undertaken by the organization. Projects implemented and advocated by the community organization during the 1960s and early 1970s guided the development of the neighborhood over the subsequent three decades, and helped redefine both the physical landscape and character of the Moreland community.

Images