The Hough Uprisings of 1966

On July 5, 1966, Mayor Ralph S. Locher unveiled an eight-point peace program meant to alleviate racial tensions in Cleveland. Prepared by Locher’s administration, businessmen, politicians, community activists, and religious leaders, the pact forged a symbolic peace between the city government and Cleveland’s African American community in response to an eruption of violence in the Hough and Glenville neighborhoods. For four nights beginning June 23rd, bands of youths roamed the East Side. Rocks, bottles and fire bombs were thrown from moving vehicles, a handful of pedestrians were assaulted, and vandals targeted businesses near Superior Avenue and East 79th Street. Upwards of 200 policemen patrolled the area. A helicopter loomed overhead, directing police battalions towards congregating youths. Showcasing recently acquired white helmets, riot sticks and tear gas guns, the uniformed squads evoked imagery reminiscent of civil rights unrest in the American South. While some community members considered it a “violent demonstration,” others attributed the outbreak to teenagers blindly striking against society. In reality, racial inequality and the economic disparities endemic in segregated neighborhoods lay at the root of the violence. As reported by Cleveland’s African American newspaper, the Call and Post, the local government was “dealing with dynamite, and ”…a crash program of reform” was necessary to avoid further racial violence.”

In large part, the unrest grew from distrust of Cleveland’s government, particularly the police force. Longstanding racial tensions with neighboring white communities set the stage; two white men fired a gun from their vehicle into a group of African American boys that had been throwing rocks at passing cars. A ten-year-old child was hit in the groin and admitted to the hospital. Rumors quickly spread that attending police officers refused to take descriptions of the young witness’s assailants. A crowd gathered and began pelting the police with rocks. The ensuing peace pact recommended a full investigation of the shooting, impartial handling by police of all persons involved in the disorder, full integration of the police force, the holding of a mass community meeting, the creation of a committee to investigate the needs of inner-city areas, an investigation into incendiary race hate literature recently circulated on the East Side by white supremacists, and the employment of specially trained police officers in the affected neighborhoods until tensions abated. The efforts proved ineffective in quelling the unrest. By month’s end, Cleveland joined a growing number of U.S. cities that became grounds for violent social uprisings during the 1960s.

During the week-long uprising, four African Americans died and an incalculable amount of property damage was incurred due to widespread fires and looting. This second revolt, also a response to the inequalities faced by the Black community living on Cleveland’s east side, became known as the Hough Riots. Similar incidents had become increasingly common – and feared – in northern cities. Civil disorder in the form of “race riots” had become a costly bargaining unit for marginalized communities abandoned by governing institutions. Each of these aging industrial centers had previously been remolded in the face of segregation and suburbanization.

Hough first developed as a product of suburbanization. The area took its name from Oliver and Eliza Hough, who settled there in 1799. Before the Civil War, the area was primarily farmland. Hough became an exclusive community following incorporation into the City of Cleveland in 1873, and housed some of the city’s most prominent residents and private schools. Spanning about two square miles, the Hough neighborhood was bordered by Euclid and Superior avenues and East 55th and 105th streets. As Cleveland industrialized and expanded outward through World War I, wealthy residents of Hough increasingly moved further east to newer suburbs. Many homes were split into apartments, and Hough became densely populated with white working and middle class residents by mid century.

Much of Cleveland’s African American community concentrated in the Cedar-Central neighborhood to the south of Hough during this time. Previously displaced by downtown housing clearance projects meant to guide business district growth in the early 20th century, the Black community was upended again in the 1940s as city officials pursued highway development and so-called urban renewal in Cedar-Central. Restrictive banking and real estate practices, in combination with segregated public housing placement, steered displaced African Americans towards the Hough and Glenville neighborhoods. With an influx of Black migrants from the South during the Second Great Migration, Hough transitioned from a white to a Black community by 1960. White residents left en masse, moving to Cleveland’s west side and newly developed suburbs. These neighborhoods forged their identities in contrast to emerging communities of color, and systemically excluded African Americans. Even as whites fled Hough, the neighborhood’s population peaked at over 83,000 in 1957 before dropping to about 72,000 in 1966. At the time of the uprisings, 90% of Cleveland’s Black community lived in Black neighborhoods on the city’s east side. Cleveland had become one of the nation’s most segregated cities. As Black residents crowded into Hough, the proximity to available jobs diminished with a concurrent exodus of industry to the suburbs, leaving African Americans in mostly low-paying, unskilled jobs. Inadequate schools and the resistance of local trade unions to integrate only exacerbated the impact of high Black unemployment.

The influx of new residents moving into Hough taxed available resources. Schools were overcrowded, garbage amassed on side streets and open lots, and the community lacked recreation spaces. Virtually no new homes had been built in Hough since World War II. To accommodate the growing population, aging residences were further broken into units. The city did little to enforce existing housing codes that governed occupancy and living standards. Vacant homes deteriorated, becoming hazards to the community and breeding grounds for vermin. Even as Hough’s physical condition declined, residents were regularly charged high rents due to the limited housing options available to the Black community in Cleveland and the refusal of suburbs to accept Black residents.

City officials publicly recognized the deteriorating state of Hough, but did little more than offer well-intentioned proposals and plans. The University - Euclid urban renewal project was one of two major redevelopment plans unveiled in 1960. The scope of this massive project included much of the Hough neighborhood. In a move away from the “slum clearance” approach to urban development, the plan emphasized housing rehabilitation and the development of recreation spaces. The project rolled out with fanfare, but soon faced delays and funding setbacks.

Despite resource inventories and grand promises, only a handful of scattered rehabilitation efforts in Hough came to fruition by 1966. While delays were often tied to federal and local oversight of the massive endeavor, completed work was typically over budget and behind schedule. The city administration appeared to be diverting its resources towards the Erieview renewal area in downtown rather than aiding struggling east side neighborhoods. Speculation also grew that the local authorities were allowing Hough to become blighted in order to lower the cost of acquiring land for a proposed Heights Freeway project. Marred by general disorganization and administrative mismanagement, the federal government eventually froze funding for Cleveland urban renewal projects. Vacant lots littered with dirt and rubbish quickly became the most common evidence of renewal efforts in Hough.

While city officials did little to stem the impact of suburbanization and segregation on Hough, the administration’s law enforcement branch physically embodied and actively reinforced discriminatory policies and practices that promoted social inequality. A longstanding tradition of hostile relations existed between Black residents and the police. Charges of police brutality and a dual system of law enforcement persisted throughout the 1950s and 1960s, but were dismissed by a predominantly white city administration. An independent report in 1965 found that only 175 of the force’s 2,100 employees were Black. Only two held rank above patrolman, and few were assigned duty to west side neighborhoods.

Cleveland’s segregated police department was racially unrepresentative of the community it served, and offered no recourse for civilian grievances to be heard. While many residents of Hough advocated for a stronger, integrated police presence in order to deter crime, complaints regularly surfaced concerning the department’s use of excessive force and practice of turning a blind eye toward racial violence against the Black community. Throughout the 1960s, instances of violence perpetrated by African Americans against white victims resulted in public outrage and swift arrests, often with little evidence. In cases of racially motivated attacks against persons of color, police often blamed the victims for inciting violence. In the years leading to the unrest in Hough, Locher’s administration refused to meet with community groups concerning mounting claims of physical and verbal abuse against Cleveland’s Black community. As racial tensions grew, Cleveland’s police department became a symbol of the city administration's alignment with white interests. Beginning on July 18, 1966, and lasting approximately one week, residents clashed with police as discontent over living conditions and systemic racial injustice surfaced in Hough.

Sparked by a minor racially charged dispute at a neighborhood bar at East 79th Street and Hough Avenue, the July uprising in Hough brought widespread looting, arson and destruction. While impacting the entire community, primary targets were white-owned stores, abandoned buildings, and residences owned by absentee landlords. As symbols of civic authority, police officers and firemen were met with violence; no white civilians were attacked. Conversely, an African American was fatally shot by a patrol of white vigilantes while driving to work. Three additional Black residents of Hough were also killed by unknown assailants during the week.

Outbreaks of violence diminished in severity beginning July 22nd. Local ministers, civic leaders and community activists met the following morning in an effort to establish peace and address the problems that incited the tragic events. Mayor Locher refused to attend, but was presented with the underlying causes of the uprising on July 25th in City Council by Hough area councilman M. Morris Jackson.

(I)t was not without warning. The warnings were in the broken promises of urban renewal, Mr. Mayor. The warnings were seen in the continued existence of rat-infested buildings that should have been renewed long ago. The warnings, Mr. Mayor, were in the inadequate recreation facilities, insufficient city services, lack of employment, and the failure to integrate the police force. These were the seeds of discontent that exploded last Monday night…where do we go from here, Mr. Mayor?

A special session of the Cuyahoga County Grand Jury convened that same day to explore the causes of the riot. Headed by former Cleveland Press editor Louis B. Seltzer, an all-white jury of non-Hough residents presided. Following a bus tour of Hough and interviews with residents, law enforcement, civic leaders and government officials, the fifteen-member committee released their conclusion in a report on August 2, 1966. They determined that the uprising was instigated by a small, organized group of extremist agitators with communist leanings. The police force was exonerated of all wrong-doing and abuses, and stricter sentences for crimes committed during riots were recommended. While acknowledging Hough residents faced social and economic inequalities in their daily life, the committee did not considered these to be causes of unrest. Instead, the jury asserted that radicals had exploited these conditions to provoke teenagers into rioting. The report not only dismissed the possibility that Hough residents had agency in their decision to participate in or support the uprising, but exonerated the city government from culpability in creating conditions that fostered civil disorder. Exemplifying their misreading of the situation, the committee concluded that the “Negro community may be moving too fast for the total community to bear”; Cleveland was not ready to accept African Americans as equal members of society.

The report, lauded by Mayor Locher, sparked outrage in Cleveland’s Black community. Its findings were quickly refuted by both federal and community sponsored investigations into the unrest. No evidence was found to corroborate the jury’s findings that Communist agitators were responsible for inciting or propelling violence. Instead, a citizen committee organized by the Urban League of Cleveland determined that the city’s disregard of social conditions in Hough “led to frustration and desperation that…finally burst forth in a destructive way.” The committee documented numerous examples of the police exacerbating unrest through use of derogatory slurs and excessive force. These different readings of the uprising in Hough were an ominous predictor of a long and difficult road ahead for efforts to rebuild the neighborhood.

Despite an influx of federal funds for rehabilitation, the economic and physical condition of Hough did not dramatically improve in the wake of the 1966 uprisings. Social unrest, accompanied by widespread looting and arson, would revisit the area during the summer of 1968 following a shootout between police and Black nationalists. The population of Hough rapidly declined as more suburbs slowly began to open up to Black residency. Even as overcrowding subsided, the inability of local government to address issues of segregation, racial discrimination, economic and social inequality, neighborhood deterioration, and poor police-community relations continued to impact Cleveland’s communities of color. Institutionalized policies and practices that reinforced the underlying causes of the 1966 Hough uprisings had been inscribed into the landscape, and would continue to guide the trajectory of Cleveland’s development over the proceeding decades.

Video

Audio

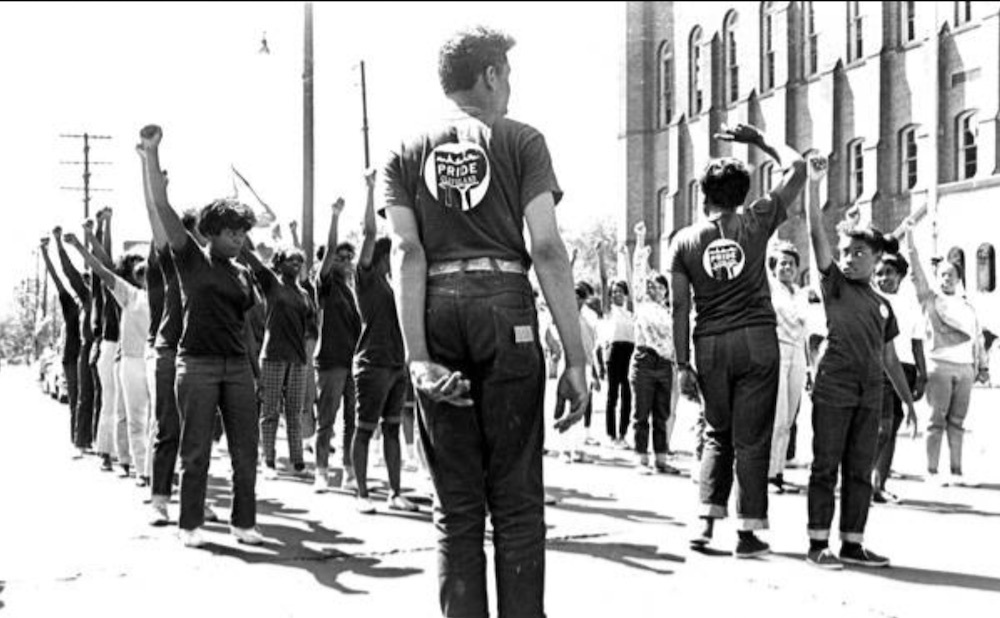

Images