Oliver Mead Stafford

At the turn of the 20th century, Cleveland already had its own version of today’s Donald Trump. Oliver Mead Stafford may have come from money, but he also had a talent for making and raising it, while he ceaselessly strived to keep up with the Joneses—or more precisely, the Rockefellers, Wades and Hannas of the city. He led a range of successful businesses, sat on many influential boards, and was always a prominent, if not extravagant, philanthropist. Despite his efforts, some rather questionable, he never quite rose to the lofty heights of Cleveland’s more famous business elite. His family proved frequent sources of disappointment and concern for him, and soon squandered the fortune and sullied the legacy he diligently created. Today, his name still graces a successful insurance firm he started, and a work of art he proudly commissioned remains on the wall of a Cleveland church, but the driven and successful Cleveland businessman never quite emerged from the shadow of his illustrious neighbors, and he is now largely forgotten.

Stafford was born February 7, 1851, at the family house on the corner of Broadway and Forest Street (now East 37th). Although he would never serve, there was always a strong commitment to the military in the Stafford family. His father, Jonas, was a veteran of the War of 1812, and both of his uncles lost their lives in the Civil War. Stafford’s wife, Maude Evelyn Frankland Fish, was even a cousin of Lincoln’s irksome general, George McClellan. His youngest son Frankland left college in order to enlist during World War I, and Frankland’s own son would later be captured by the Japanese in the Second World War and spend the entire war as a POW at a camp in Java. The family’s strong military allegiance surely played a role in the discipline and mental toughness Stafford displayed in his own business activities.

Always an elitist, Stafford disdained higher education for mere commoners, and believed the path to success was found through experience, dedication and hard work. He arrogantly proclaimed these attitudes in a page-long ‘how-to-succeed-in business’ article for the Cleveland Plain Dealer in February 1912. Although he felt very few would benefit from extended education, he sent both of his own sons to Yale--ostensibly to capitalize on the connections they would make there.

As a young man, Stafford ventured west for a short time to serve as a teacher on the frontier, but soon returned to Cleveland where his father installed him in menial positions throughout the real estate firm, E. Fish & Company, hoping Oliver would work his way up and succeed him in the organization. This is a practice Stafford took to heart, and he later did the same with his own sons. He certainly benefitted from the head-start his father’s success provided him, but by the time Jonas had died in November 1873, in the same house Oliver was born in almost 23 years before, he was already establishing himself as one of the city’s up-and-coming businessmen.

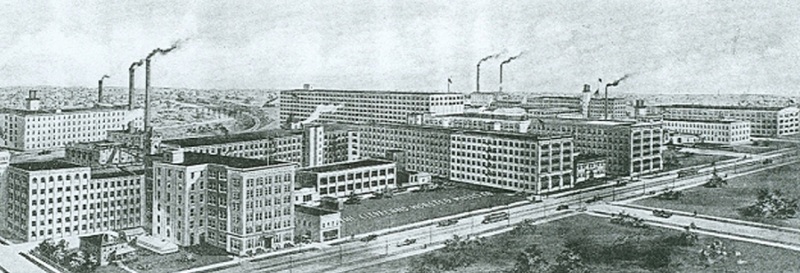

Stafford had already struck out on his own by 1883, when he conducted a succession of real estate deals where he seems to have been uncannily proficient at buying properties at relatively low prices and quickly selling them for substantial profits—some might say, too uncannily, but nothing illegal was ever proven. He is perhaps best remembered as the president of the Cleveland Worsted Mills Company. He was instrumental in re-organizing the then, Turner Worsted Company in 1895, when it was valued at just under $43,000. He took over the company by 1902, and just a decade later Worsted Mills was worth $5 million. His tenure there often demonstrated the power he had attained and his willingness to wield it, sometimes questionably. In 1909, Cleveland’s reformist-minded mayor Tom L. Johnson accused him of stealing thousands of dollars of the city’s water to supply the factory, but the lawsuit was dropped when Herman Baehr defeated Johnson in the ’09 election and somehow agreed with Stafford that, though the city water supply had been tapped, it was for emergency purposes only, and was therefore acceptable. Stafford also threatened to close the hugely successful enterprise immediately if the woolen duty was lowered, as congress proposed, in 1905. The tariff, and the company, remained.

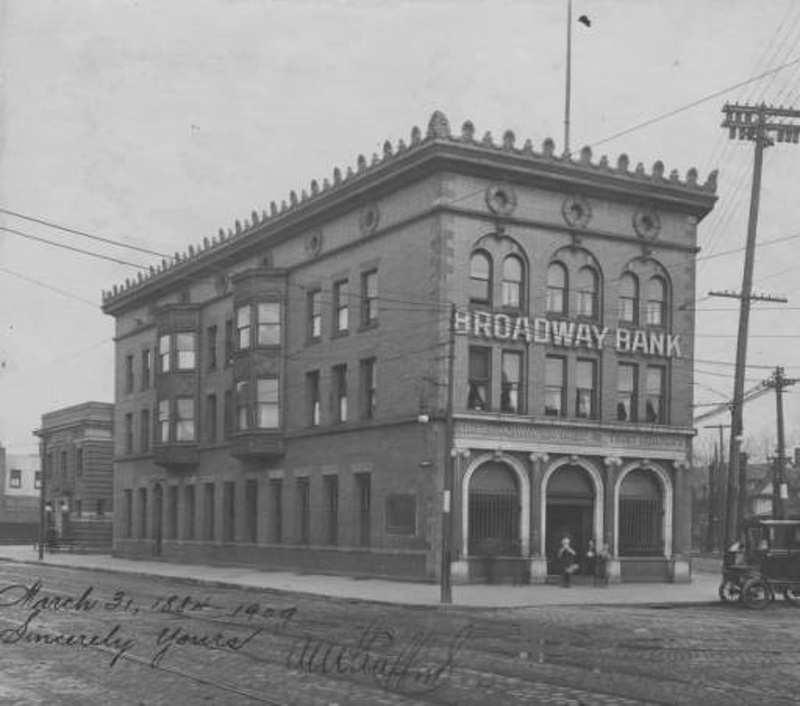

Besides running Worsted Mills, Stafford started the insurance firm OM Stafford, Goss & Bedell. When it merged in 1920 with another firm to become Brooks & Stafford Company, still operating in Cleveland today, it was the largest insurance business between Philadelphia and Chicago. He founded and served as vice-president of both the Broadway and the Woodland Avenue Savings and Trust banks, was a director of Canfield Oil Company, president of Market Street and Storage, president of the Cleveland Public Library, treasurer of St. Alexis Hospital, and was a charter member of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce. He was also the long-time superintendent of the Broadway United Methodist Church. In 1924, he commissioned the artists, Armando Vandelli and Vittorio Guandalini, who had just finished restoring Leonardo’s Last Supper in Milan, to recreate the masterpiece on the wall behind the altar of the church. It was the only life-sized replica in the United States, and Stafford clearly intended it to be the enduring stamp of his legacy.

By the time of his death, just eight months before the stock market crash in 1929, the hopes of that legacy enduring were dim. His beloved son and chosen successor, Oliver Jr, had died in the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1919. Frankland replaced him in the family business, but would scandalize the city when his first wife divorced him on January 12, 1934, and he immediately remarried a former Worsted employee less than two weeks later. Although Stafford left an estate appraised at $886,313, little of it was left after a long probate battle finally ended in the 1980s. His Last Supper sits in the now-shuttered church, almost as ignored as he is—an ignominious end to Cleveland’s version of The Donald.

Images